NOTE: On October 21, 2021, the Internet Archive celebrated its 25th anniversary in a virtual event featuring this keynote address by Founder & Digital Librarian, Brewster Kahle. You can watch the talk here or read the transcript below.

Universal Access to All Knowledge has been the dream for millennia, from the Library of Alexandria on forward. The idea is that if you’re curious enough to want to know something, that you can get access to that information. That was the promise of the printing press or Andrew Carnegie’s public libraries — fueling so much citizenship and democracy in the United States. The Internet was the opportunity to really make this dream come true.

What we have is an opportunity that happens maybe only once a millennium. The opportunity that comes only when we change how knowledge is recorded and shared. From oral to manuscript, manuscript to printing, and now from printing to digital. I was lucky enough to be there in 1980 and thought: what a fantastic opportunity to try to influence that transition.

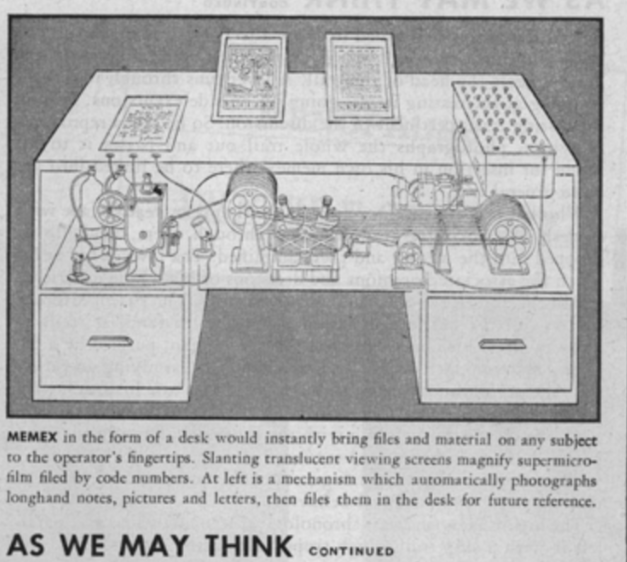

Of course, we were building on the vision of many before us. This dream of having an interlocking publishing system had been around for a long time. Vannevar Bush’s 1945 article “As We May Think” was very much on people’s minds in the 1980s. There was Ted Nelson’s Xanadu—a world of hypertext. Doug Engelbart’s way of annotating and enabling you to build on the works of others.

The key thing was not the computers. Actually, it was the network. It was the ability to communicate with each other. Sure, anybody could go and write word processing documents. That’s good. But can you make everybody a publisher? Can everyone find their voice and their community no matter where they are in the world? And can people write in a way that allows others to build on their work? By 1996, we had built that. It was the World Wide Web.

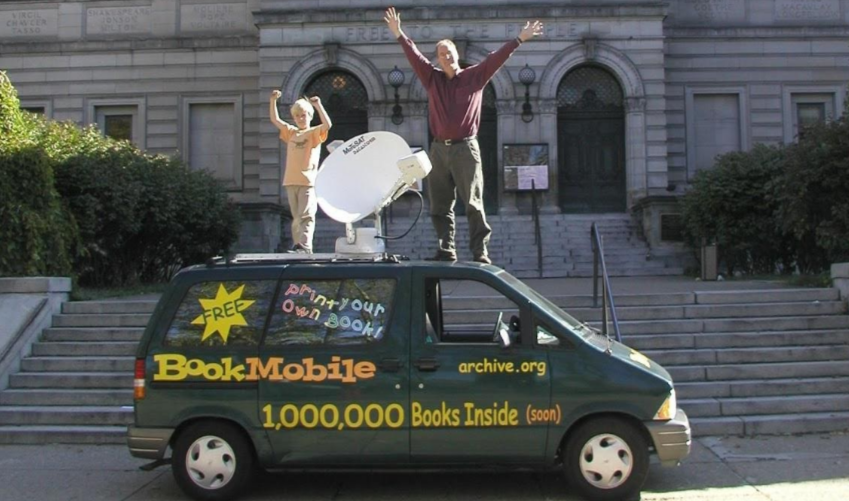

With this global publishing network, the Web, we could finally build the library. It was time to build the library. In 1996, I thought: Why don’t we just build this thing? I mean, how hard could it be? Sure, maybe we’re going to have to go and digitize a whole library, but that couldn’t be that hard, right?

And so, a group of us said, let’s do this. We started by archiving the most transient of media, which was the World Wide Web’s pages. We did that for five years before we even made the Wayback Machine. The idea was to record what people were publishing and be able to go and use that in new and different ways. Could we build a library to preserve all of that material, but then add computers to the mix, so that something new and magic happens? Could we connect people, connect ideas, build on each other’s concepts with computers and these new AI things that we knew were coming. Ultimately could we make the world smarter?

Could we make people smarter by being better connected? Not just because they could read what other people were writing, but because machines would help filter information, scan vast amounts of knowledge, emphasize what is most important, provide context to the deluge.

In many ways, we have achieved this, but not completely enough: now people are writing and sharing knowledge, but it is intermingled with misinformation — purposefully false information. We still don’t have the tools to filter out the lies, and in many ways, we have business models that prosper when misinformation is widely shared. So while the dream of access may be at hand, we lack the tools and responsible organizations to help us make good use of the flood of data now at our fingertips. Given how new our digital transition is, this may not be that surprising, but it is an urgent issue that faces us. We need to fight misinformation and build data-mining tools to leverage all this knowledge to help people make better decisions — to be smarter.

This is our challenge for our next 25 years.

When we started the Internet Archive, I felt this project needed to be done in the open and as a non-profit. We needed to have not just one or two search engines, we needed lots and lots of different organizations building their new ideas on top of the whole knowledge base of humanity. We could help by being a library for this new digital world.

The libraries I grew up with were vast and free, and came with librarians who helped me understand and find things I needed to know. In our new digital world, that future is not guaranteed. It may be that most people will just feed on what they can access for free, placed there because it’s promoted by somebody. If we don’t solve this–getting quality published material to the internet population–we’re going to bring up a generation educated on whatever dreck they can find online. So we have to build not only universal access to lots of webpages, but access to the right and best information– Universal Access to All Knowledge. That is going to require requiring changes to existing business models and adjustments by long standing institutions. We need an Internet with many winners. If we have an Internet with just a few winners, some big corporations and large governments that are controlling too much of what’s online, then we will all lose.

A library alone can not solve all of these issues, but it is a necessary component, needed infrastructure in a digital world.

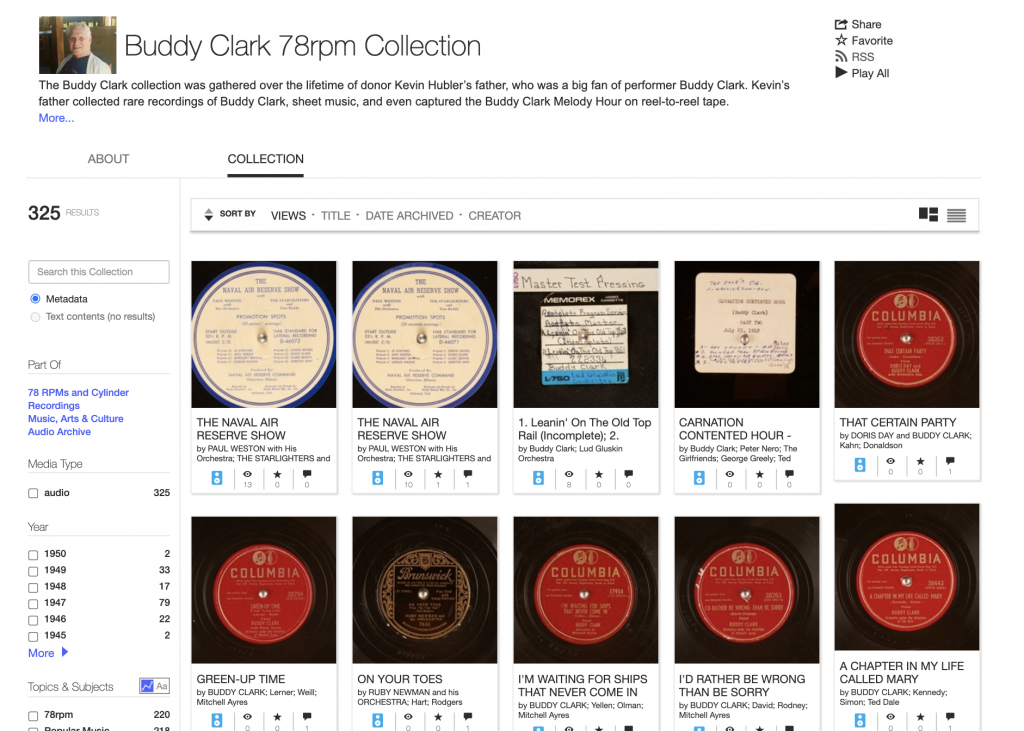

25 years ago, I thought building this new library would largely be a technological process, but I was wrong. It turns out that it’s mostly a people process. Crucially, the Internet Archive has been supported by hundreds of organizations. About 800 libraries have helped build the web collections that are in the Wayback Machine. Over 1000 libraries have contributed books to be digitized into the collections—now 5 million volumes strong. And beyond that, people with expertise in, say, railway timetables, Old Time Radio, 78 RPM records—they’ve been donating physical media and uploading digital files to our servers that you see here in this room. Last year, well over 100 million people used the resources of the Internet Archive, and over 100,000 people made a financial donation to support us. This has truly been a global project– the people’s library.

I love the weird and wacky stuff of the Internet, just the fun and frolicy things. You go online and see these things like, wow, that’s remarkable.

Yesterday, I was looking through the uploads from Kevin Hubler. He donated the collection his father built over his lifetime. His father collected everything a particular singer, Buddy Clark, had ever done. Clark was a 1940’s big band singer who died when he was 37. So I could listen to records, see sheet music, and dive into details, all thanks to Kevin Hubler. I love this– going down rabbit holes and learning something deeply. This was a tribute to Buddy Clark, but also to Kevin and his father– who prepared and preserved something they loved for the future.

That we’re able to enjoy each other and to express our wackiness– that’s the win of the World Wide Web! That’s the thing that you wouldn’t get if it were all just more channels of television. Yes, the internet and the World Wide Web are a bit of the Wild West, but would you want it any other way? Isn’t that where the fun and interesting things come from?

Today, it is still the people’s internet. That’s the internet that I wanted to support by starting the Internet Archive. The World Wide Web is an experiment in radical sharing where people feel that they’re better off, not worse off, building on other people’s works.

I’m hopeful and optimistic that we can build this next 25 years to be as interesting and fun as the last. That we can usher in another level of technology, another 25 years of blossoming, interesting ideas.

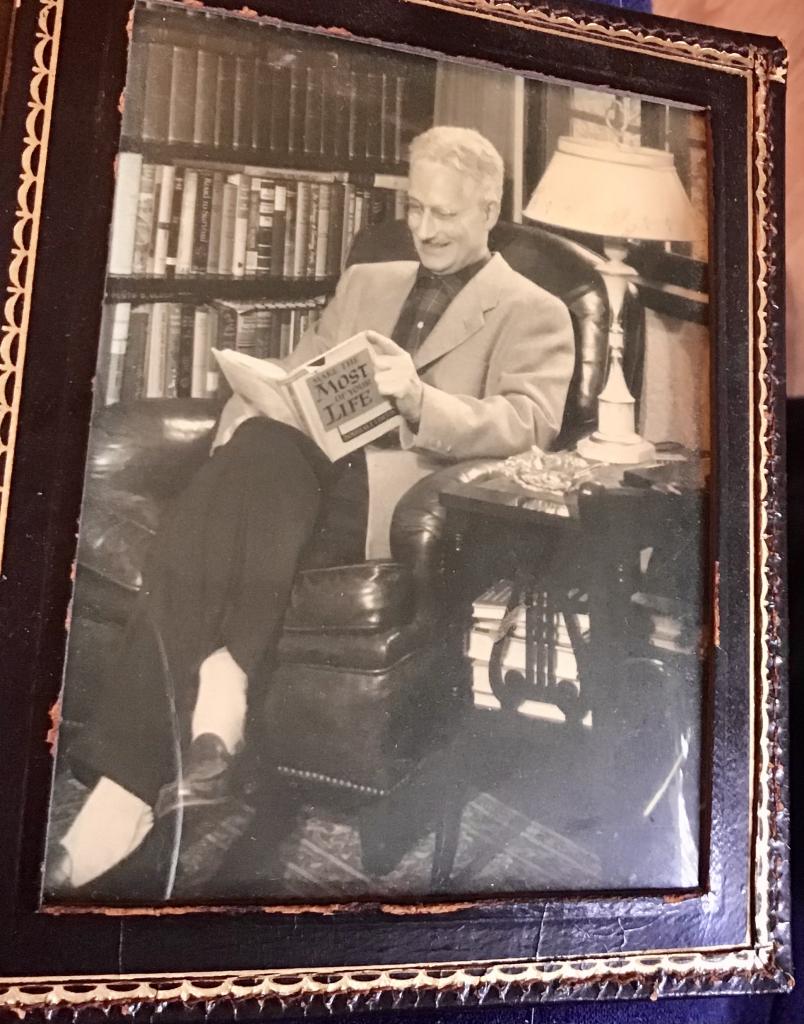

I want to end this talk with a personal story– my grandfather Douglas Lurton was a publisher and an author who died before I was born. Last weekend I searched for his name using full text search in the 20 million texts now on the Archive and found this quotation from him in a newspaper from West Sacramento: “Take the tools in hand and carve your own best life.” — Douglas Lurton

Now, I would like to extend my grandfather’s advice. “Let us all take our tools in hand, and together, carve our own best future.”

Let’s keep the trust.

Certainly these are the people who can do the most to help digitize, and nothing beats more than unity.

great post

Its not specifically any advancement in technology that has caused such misinformation, but it has been greatly fueled by advertisers. I don’t necessarily mean advertisers directly, but the algorithms created by advertisers in order to deliver content which matches the individual using secret perfect data about them. The algorithms are content neutral and, (as we all know), will consistently promote the most polarizing content for clicks in addition to content which reinforces the world view of the user.

Furthermore, I’d say traditional monetization models, specifically intellectual property is the biggest obstacle in the way or achieving ultimate freedom of information. We live in a post scarcity age for data and information. Things can be copied in seconds with minimal effort or resources. Intellectual property can not keep up with this and is holding us back. How can anyone own information or ideas? Markets depend on scarcity, but when it comes to computer data, there is none, so the only way to make money is through arbitrary, (and what I view as illegitimate), paywalls. You can argue renting access to data in some cases is fine, and I might agree, but paying for a file which takes no effort to copy is a rip off.

We could literally have all the worlds information, art, and entertainment that has ever been archived in the palms of our hands, in every house hold humans live, but we are holding ourselves back for the sake of arbitrary things we take for granted in our society. I’m afraid it may already be too late.

Libgen is taking great steps in this direction

Yeah Libgen.fun has done a great job by moving over to the decentralized web.

Libraries may begin as collections, but the proof is in the sharing, the circulating, the access. Good essay, happy anniversary.

I just made a donation, and answered the question of why I had done so by saying “Some day maybe we’ll learn the lessons of history if somebody remembers what actually happened…”

We keep making the same mistakes over and over, and the reasons why keep getting whitewashed.

Perhaps this noble effort can bring some transparency, as well.

At the end of the day it is ourselves to blame for the wrong that we do in this world.

No one should dedicate themselves to be a separatist of the world that we live in.

No Cap, Wall Text(s) are addictive let’s try to reduce the Wall Text(s).

When it comes to archiving, a major obstacle to overcome is personal prejudice and small mindedness on the curator’s part. I see it all the time with special collection libraries and museums I deal with. Many times the digital material I’ve tried to place as a donation with special collection libraries has been refused because I have it or a portion of it online. And what happens down the road? The prejudiced people that run some of these online sites remove it. Now where is it?

But besides that, there is no comparison with having material at your fingertips, on disc or or the server when it comes to searching through it as compared to trying to search through it online or try to download it with slow and spotty internet service that some of us have. In addition, these small minded archives would have the hi-resolution digital material in their collection and not the lower resolution material that is online. And they could provide a backup to the online material as well. But they just don’t get it.

And since I brought up resolution, keep that in mind with your archival work. I see a lot of things archived that are terrible resolution. Sometimes we have no choice and low resolution is all that we can get. But if you have a choice, archive in decent resolution online. Use resolution that could make a decent facsimile, if one day all that is left for the historical record is your last extant copy.

Daniel D.Teoli Jr. Archival Collection

Daniel D.Teoli Jr. Small Gauge Film Archive

Daniel D.Teoli Jr. Advertising Archive

Daniel D.Teoli Jr. VHS Video Archive

Daniel D.Teoli Jr. Audio Archive

Daniel D.Teoli Jr. Social Documentary Photography

Libraries may begin as collections, but the proof is in the sharing, the circulating, the access. Good essay, happy anniversary.

You are right– access is the goal

Are you wining the lawsuit yet.

thanks a lot

great post dear kahle

Another of my ideas is to teach these important things to children from an early age

Concerning the preservation of history – how is the longevity of the Wayback Machine data being ensured?

We all should be endlessly grateful for Mr. Kahle’s presence of mind and foresight, back when he decided that this might be something worth archiving. Amazingly, nobody else did, and now the Internet Archive holds the only record of this massive part of what made up the past quarter century of human history. And the thought that this is only kept and guarded by one organisation frightens me. This is a huge part of our society’s and humanity’s heritage in the digital age. Its preservation should be a major international concern. Frankly, I’m surprised that world leaders, foundations, philantropists, don’t see the spindly legs this currently stands on as something that needs addressing, urgently!

I can’t count the areas and projects, both personal and professional, in which I have relied on finding information that only the Wayback Machine still holds on to. If, heaven forbid, it should disappear – such as through a misguided, frivolous lawsuit from an obsolete industry trying to throw us all back into the pre-Internet age – there will just be a big gap where this part of human history used to be.

Why are governments and national libraries around the world not urgently looking into partnering with the IA to create their own copies, and contribute to the effort? Geographically, politically, financially decentralised, as it should be.

thanks for text