By Frances Sawyer

With a sharp yip and a deep ‘Ohhh’ cried into the Pacific evening sky, Kanyon “Coyote Woman” Sayers-Roods welcomed hackers, activists, artists, policymakers, and engineers from around the globe to the California Coast, traditional land of the Ohlone & Amah Mutsun peoples, to share in a week of learning, building, and dreaming a better web.

Held on a farm near Pescadero, California, the first ever DWeb Camp brought together more than 375 campers from six continents to workshop, relax, build, and strengthen the community working on the decentralized web. The camp followed in the footsteps of the 2016 Locking the Web Open Summit at the Internet Archive and the 2018 Decentralized Web Summit held at the S.F. Mint, but with a new spin: what would happen if we brought this deep conversation about technology to a sublime, wind-whipped farm on the coast and over the course of a week, built a temporary, remote, networked community of ideas and ambition in nature?

It was a week of radical creation! A little bit Burning Man, a little bit Chaos Communication Camp, DWeb Camp proved raucous, thoughtful, experimental and energizing for all involved.

Here are a few highlights from the week:

The Mushroom Farm

After scouting a half dozen sites, Wendy Hanamura, leader of the DWeb organizing team had a feeling: The Mushroom Farm, could become the perfect place for this gathering. It didn’t matter that the farm didn’t quite yet have strong Internet connectivity. Or that the bathrooms weren’t scaled to 300 people’s needs. The philosophy and ethos of the farm and its stewards were absolutely aligned with those articulated by decentralized organizers — it was time for our communities to grow together to help foster deep connections within ourselves, our communities and the planet.

A few miles south of Pescadero, in sight of the waves on Gazos Beach, The Mushroom Farm was once home to one of Campbell Soup’s industrial mushroom farms — producing 70,000 pounds of mushrooms per week. More than a decade ago, it was sold in a distressed asset sale and, in the intervening years, its 700+ acres have been nurtured back to life to create a gathering place for disruptive thinking on renewable energy, regenerative agriculture, technology, and wellness.

Home to native, perennial grasslands, an experimental vegetable and hemp farm, old warehouses filled with redwood beams, and more, as a site, it channels a strain of futurism that has long been cultivated on the western edge of the U.S. For DWeb Camp participants, it proved the ideal setting to encourage long-form thinking, open dialogue, and reflection on the evolution and design of technology.

The Big Build: By Community, For Community

Four days before most participants arrived, a crew of 50+ volunteers descended upon The Mushroom Farm to muck the bathrooms, set up three sprawling tent sites, paint signs, prep food, build the camp’s shared spaces, and put the final touches on the site before the crowds arrived.

These volunteers provided the final push after months of preparations by The Mushroom Farm, DWeb organizers, experts from Custom Camps and the Internet Archive.

Together, they created an ethos of openness and respect, articulated in the DWeb Camp Pillars:

These pillars were affirmed in those first days as participants from across the globe —old friends and those who had never met— forged deep connections in the process of building the camp. From posting friendly warning signs about local ticks and poison oak crafted by Companion-Platform designers Calvin Rocchio and Lexi Visco to working with the chefs (including several Esalon kitchen alums) to enlarge the outdoor kitchen, volunteers went to work to establish a sense of community that would last throughout the week. Each night, the volunteer crew gathered for a hearty meal of local produce and cheeses, getting excited to welcome the hundreds of newcomers later in the week.

Installing the Mesh

Against this stunning natural backdrop, what’s the first thing the builders of the next web did? They built a mesh network, of course!

Several weeks before the crowds arrived, Network Coordinator, Benedict Lau of Toronto Mesh and an army of volunteers, many from People’s Open Network, scampered across the Mushroom Farm from the Mesh Hall to the campsites with zip ties, cables, routers, and wireless radios to build a working mesh network throughout the camp footprint. With 6 nodes across camp, this network allowed for full peer-to-peer connectivity for camp participants.

This early team of volunteers laid the groundwork of six nodes for the system and throughout the week, construction continued as more users were added with each arriving device. As participants arrived, they were given an introduction to the network, joined with the open credentials, then given the tools to teach others about its operation by our team of Network Stewards. On the final day of workshops, the team led the installation of the 7th node, completing the “Mesh Playground.” Soon, all were up and running full speed ahead, linking phones and laptops across the camp to Raspberry Pis in the Mesh Hall, running decentralized apps such as a Matrix Homeserver, and opening a Secure Scuttlebutt Pub on the local network — a decentralized web come to life!

Soon, supporting the mesh and teaching people about their own experiences in building community networks were leaders from around the globe: Nico Pace and cynthia el khoury, coordinators from Association for Progressive Communications helped gather community network leaders from around the world. Soledad Luca de Tena, a director at South Africa’s first community network, had flown in from Cape Town. TB Dinesh, a mesh specialist, came from Bangalore. Hiure Queiroz, Marcela Guerra and their baby Amina travelled together from Brazil. All week, Luandro Vieira smiled as he typed away and troubleshooted the network expansion, leveraging his experience in building a community network in Moinho, Quilombola village Brazil. At their side were co-creators from People’s Open in Oakland, Toronto Mesh, Guifi.net, the Internet Archive, and more. They highlighted the LibreRouter, an important open hardware being launched to address long-standing hardware problems for rural connectivity.

Opening the Gates

With the campsite and mesh ready to go, the gates of the Mushroom Farm opened Thursday afternoon and the first eager participants arrived. They had signed up without quite knowing what to expect, but as head Weaver, Kelsey Breseman noted, “anything you can be excited about without knowing what to expect is cool.”

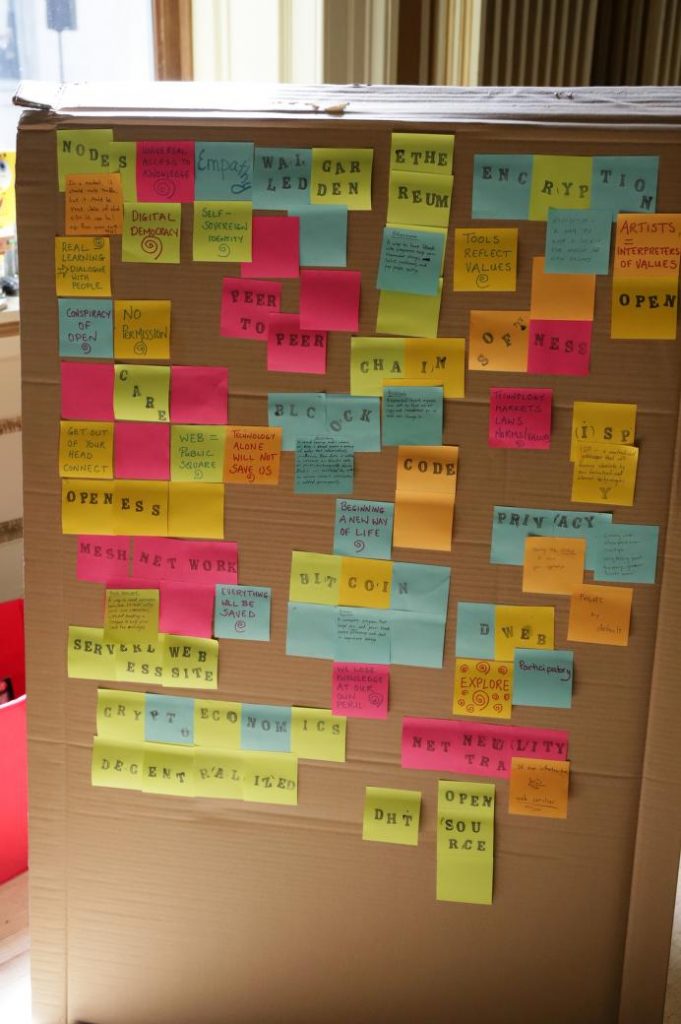

As they entered, participants were assigned a campsite and immediately welcomed into imaginative world created by the organizers. There was the Mesh Hall, the whirring, technical heart of the first ever DWeb Camp. Cables flying (neatly), drones disemboweled on tables, Oculus headsets, white boards covered with concept designs and welcome signs for mini-workshops on just about any decentralized topic imaginable.

A bit further into the campus hub, and the blockchain courtyard contained a photo-booth where participants could take a selfie with a Secure Scuttlebutt-networked camera, paint a sign about their project, or sit in the shade beneath verdant natural awnings. A few steps further, and the Universal Access Hall, where comfy low mattresses lined the walls and participants sipped tea while joining one of hundreds of small group conversations.

Hidden in different pockets throughout this space, experts from the Electronic Frontier Foundation talked policy, Secure Scuttlebutt creators imagined a new form of decentralized social media, and representatives from Consensys, Holo, Orchid, Web 3, Coil, Gun, Dat, Web Torrent, Jolocom, Protocol Labs, and Solid held court on infrastructure design, new protocols and data structures. There were spaces to talk about archiving where the Internet Archive showcased its model of a miniaturized version of its collection and the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative demoed their latest thinking on data infrastructure and political risk.

Outside the hall, the sprawling outdoor picnic area crests the bluff alongside a hang out area with a make your own name-tag button station, an outdoor kitchen, and picnic areas with countless ongoing conversations, all framed by a bonfire pit and the Dome of Decentralization. In this space, participants settled into the whimsy, the creativity, the ethos of the land. Then, for the next three days, leapt into thinking, experimenting, and creating against the backdrop of the relentless pounding of Pacific waves.

Experiments Galore!

In such a setting, experimentation reigned!

Participants brought ideas, projects in prototype, and ready to break demos, excited to have their solutions picked apart by their brainy peers. A thirteen-year-old boy, Jasper, chaperoned by his dad, worked with older coders to create a 3D map of the farm using customized software and patterned drone flights. Tables in the Mesh Room held rotating conversations about projects across the network stack: Kyle Drakeshowcased his recreation of Geocities, complete with MIDI sound files playing happily in the background. Just across the room, Bryan Newbold invited participants to print or take away some 10 million journal articles. Throughout the week, the ten DWeb Camp Global Fellows were easy to find, leading discussions on building community networks and P2P apps and sharing their experiences as local leaders of decentralization. Every once in awhile, these conversations were interrupted by a new murder as a campus-wide game of ASSASSINS played out.

The energy of the hacker space permeated the whole of the conversation and constantly reminded participants that the theories discussed, values articulated, and ideas for a better web were not simply abstract wish lists, but services that can and should be built.

Old Guard & the New

For the young creators in attendance, there was inspiration and caution offered by a host of the early pioneers of the Web. Sir Tim Berners Lee was in attendance, offering the history of the World Wide Web. Mary Lou Jepsen, who held senior product roles at Google and Facebook, hosted a conversation on privacy and the emerging central role of big data in the biomedical field. Brewster Kahle hosted a data swap, diving into conversations about the Internet Archive, archiving, and the evolution around the decentralized web conversation.

The last evening, an impromptu gathering of the “Old Guard” as they self-branded took place long into the night. What was it like when the web was just starting? What worked and what didn’t? They told and retold the origin stories of the field, leaving younger participants with the tingling feeling that history was not so removed, but pulsing, present and a part of us.

Wayback Wheel & A New Ethos for the Web

The southern end of the campsite was framed by a very sacred space, the Wayback Wheel. This piece, a beautiful canopied structure framing an open fire built by Joshua Tree, originated at Standing Rock and then traveled to Burning Man. Only before DWeb Camp did it find its home on the Mushroom Farm. Oriented toward the cardinal directions, this piece was programmed throughout the week by the artistic-technological educator Andi Wong and proved a centering sculptural home for conversations around the values of decentralized technology and building a world with respect for the elements and earth.

At the Wheel, the camp worked to center indigenous voices — beginning with Kanyon’s opening welcome and threaded throughout with indigenous and tribal representation from across the globe present. There Andi also hosted hands-on activities for the children in attendance, whose ages ranged from a few months old to teens, helping them make art and create their own world within the camp. It also corralled conversations with Earth Species Project founders, Brit Selvitelle and Asa Raskin on whether and how we could use neural nets and machine learning to understand animal communication. Over cocktails one night, about 20 attendees gathering to discuss the rapidly changing climate — and the role technologists have in contributing toward solutions.

By design and thanks to the supportive setting, this conversation about values permeated throughout the week. In a dynamic, well-attended talk in the Hyper Lounge, Asa Raskin and Tristan Harris from the Center for Humane Technology gave a talk about how lightspeed advances in technology (and particularly ad-based business models) have overwhelmed our natural evolutionary defenses. Later, they listened intently to a group of Web 3.0 builders and brainstormed solutions to making more human-centered technologies. These global ethicists came to learn how decentralization could play a role in that better future.

The importance of these big conversations were wonderfully framed by Mai Ishikawa Sutton in her blog post, “Transforming Ourselves to Transform Our Networks” at the beginning of camp. And perhaps the greatest gift of DWeb Camp to its participants was that it created a relaxed, thoughtful space that could build the trust needed to have these hard conversations.

Onward: Homeward Bound with a Call To Action

Whether dancing away by firelit to SF Airship Acoustic, sharing stories over a cup of hot cacao, or laughing riotously during the talent show, participants at DWeb Camp fostered the relationships that will only strengthen this movement toward a better web. The space offered by the Mushroom Farm and cultivated by the DWeb Camp creators and all its partners proved natural home to the kind of slow conversation that creates lasting friendships. It was a place that returned those of us engaged in decentralization to our first principles and democractic ideals, clarified by sunshine and sharpened by the cold and salty Pacific.

Now, participants have scattered across the world — they have become, again, decentralized — but the community built above the crashing waves of Gazos Beach is living on, imagining, designing, and building a better shared future through technology and community.