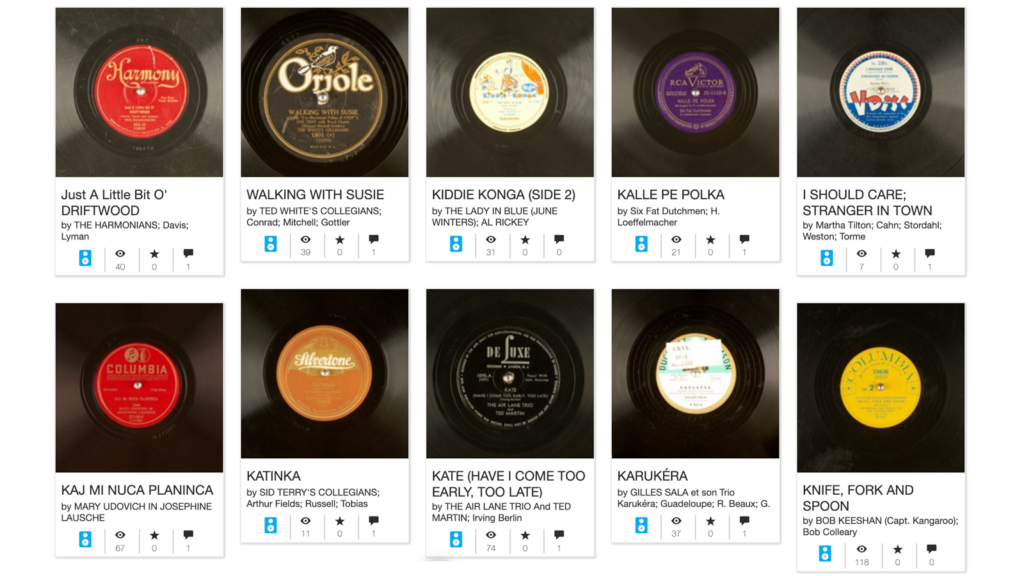

BGSU Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives partners with Internet Archive to provide digital access to thousands of historic recordings

The BGSU Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives, one of the largest collections of popular music at an academic institution in the United States, has partnered with the Internet Archive’s Great 78 Project to digitize thousands of records made in the early 20th century.

The University’s collection of over 100,000 of these discs represents one of the largest collections processed by the Internet Archive’s Great 78 Project, a program dedicated to the preservation and dissemination of these early recordings.

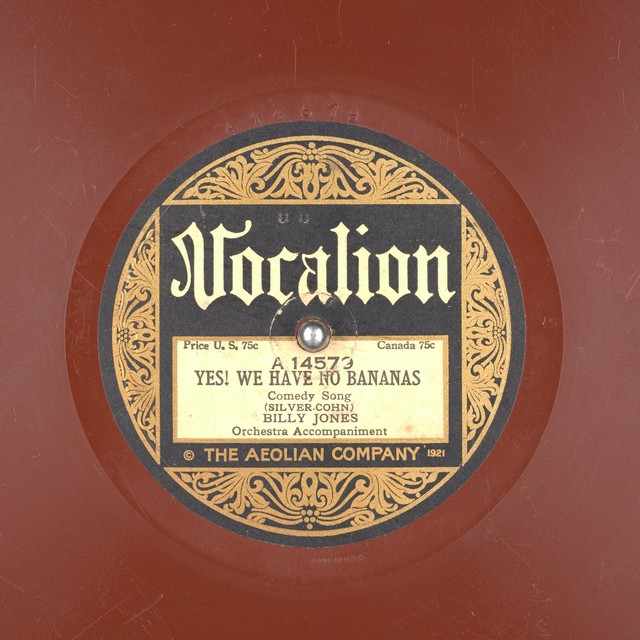

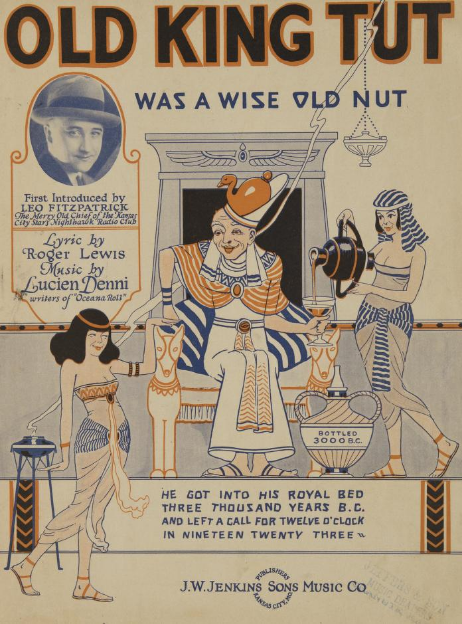

The recordings from the BGSU Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives’ collection trace the history of the recording industry in the United States, including many standard popular and jazz tunes, as well as more niche materials.

Many of the less-common items, such as recordings made by and for immigrant and minoritized groups in the United States, children’s recordings and novelty records, are only available on the original recordings since they were never released on LP, CD or digital streaming services. The collection establishes a digital record of underrepresented artists. It also reflects the cultural and political atmospheres of each time period in which the original material was pressed, meaning that some of the materials included reflect stereotypes and language that may be offensive to today’s listeners. These materials do not represent the values of Bowling Green State University, University Libraries, and Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives.

Digital versions of these records created through the partnership make it easier for BGSU to provide on-campus access to the recordings while adding those digital files to the thousands already digitized by the Great 78 Project.

Early phonograph records were made to spin at 78 revolutions per minute (rpm) and were the most common format for sound recordings in the United States from the early 1900s until the early 1950s. Because of their age and the developing practices of the early sound recording industry, these discs require specialized equipment for modern playback and, unlike modern LPs, often require the attention of a professional audio engineer to coax optimal sound quality from the aging records.

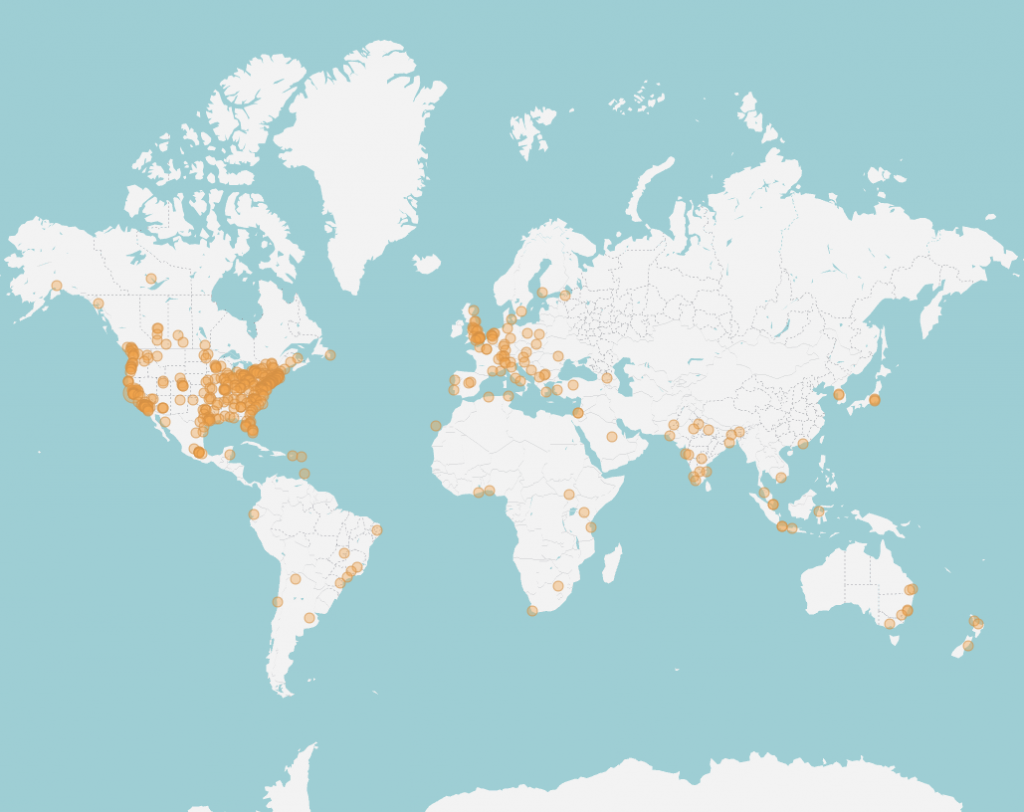

“The pace at which George Blood LC, the vendor working with the Great 78 Project, began processing and digitizing the collection was astounding,” said Dr. David Lewis, a former sound archivist at the Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives. “Within two months, they had digitized and uploaded thousands of recordings to the Bowling Green 78 rpm Collection page. That same work would have taken years longer to complete in-house at BGSU. Working with the Great 78 Project has the added benefit of contributing the University’s materials to a global network of fans, researchers and listeners alongside many other collections of 78 rpm discs.”

The digital files created from BGSU Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives’ 78 rpm discs will be preserved by the Internet Archive and made available for online listening and downloading from the Internet Archive’s BGSU collection page.

In addition, staff at the Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives will begin work to preserve copies of selected digital items from the project at BGSU, providing additional safeguards for Ohio-related content and other rare and unique recordings that align with major collecting areas in the sound archives as well as faculty research and teaching.

The wide access provided by the Internet Archive’s Great 78 Project, combined with the rare and unique material contributed to the project by BGSU, will add to the depth and breadth of material available both on campus and through the Internet Archive.

Reposted with permission from BGSU News.