Jason Scott presents Internet Memes of the last 20 Years at the Internet Archive’s 20th anniversary celebration.

——–

It’s always going to be an open question as to what parts of culture will survive beyond each generation, but there’s very little doubt that one of them is going to be memes.

Memes are, after all, their own successful transmission of entertainment. A photo, an image that you might have seen before, comes to you with a new context. A turn of phrase, used by a politician or celebrity and in some way ridiculous or unique, comes back you in all sorts of new ways (Imma let you finish…) and ultimately gets put back into your emails, instant messages, or even back into mass media itself.

However, there are some pretty obvious questions as to what memes even are or what qualifies as a meme. Everyone has an opinion (and a meme) to back up their position.

One can say that image macros, those combinations of an expressive image with big bold text, are memes; but it’s best to think of them as one (very prominent) kind of a whole spectrum of Meme.

Image Macros rule the roost because they’re platform independent. They slip into our lives from e-mails, texts, websites and even posted on walls and doors. The chosen image (in this example, from the Baz Luhrman directed Great Gatsby) portrays an independent idea (Here’s to you) and the text compliments or contrasts it. The smallest, atomic level of an idea. And it gets into your mind, like a piece of candy (or a piece of grit).

It can get way more complicated, however. This 1980s “Internet Archive” logo was automatically generated by an online script which does the hard work of layout, fonts and blending for you. When news of this tool broke in September of 2016 (it had been around a long time before that), this exact template showed up everywhere, from nightclub flyers to endless tweets. Within a short time, the ideas of both “using a computer to do art” and “the 1980s” became part of the payload of this image, as well as the inevitable feeling it was even more cliche and tired as hundreds piled on to using it. The long-term prospects of this “1980s art” meme are unknown.

It can get way more complicated, however. This 1980s “Internet Archive” logo was automatically generated by an online script which does the hard work of layout, fonts and blending for you. When news of this tool broke in September of 2016 (it had been around a long time before that), this exact template showed up everywhere, from nightclub flyers to endless tweets. Within a short time, the ideas of both “using a computer to do art” and “the 1980s” became part of the payload of this image, as well as the inevitable feeling it was even more cliche and tired as hundreds piled on to using it. The long-term prospects of this “1980s art” meme are unknown.

And let’s not forget that “memes” (a term coined by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene) themselves go back decades before the internet made its first carefully engineered cross-continental connections. Office photocopies ran rampant with passed along motivational (or de-motivational) posters, telling you that you didn’t need to be crazy to work here… but it helps! Suffering the pains of analog transfer, the endless remixing and hand touchups of these posters gave them a weathered look, as if aged by their very (relative) longevity. To many others, this whole grandparent of the internet meme had a more familiar name: Folklore.

And let’s not forget that “memes” (a term coined by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene) themselves go back decades before the internet made its first carefully engineered cross-continental connections. Office photocopies ran rampant with passed along motivational (or de-motivational) posters, telling you that you didn’t need to be crazy to work here… but it helps! Suffering the pains of analog transfer, the endless remixing and hand touchups of these posters gave them a weathered look, as if aged by their very (relative) longevity. To many others, this whole grandparent of the internet meme had a more familiar name: Folklore.

Memes are therefore rich in history and a fundamental part of the online experience, passed along by the thousands every single day as a part of communicating with each other. They deserve study, and they’ve gotten it.

Websites have been created to describe both the contributing factors and the available examples of memes throughout the years. The most prominent has been Know Your Meme, which through several rounds of ownership and contributors has consistently provided access to the surprisingly deep dive of research a supposedly shallow “meme” has behind it.

But the very fluidity and flexibility of memes can be a huge weakness — a single webpage or a single version of an image will be the main reference point for knowing why a meme came to be, and the lifespan of these references are short indeed. Even when hosted at prominent hosting sites or as part of a larger established site, one good housecleaning or consolidation will shut off access to the information, possibly forever.

But the very fluidity and flexibility of memes can be a huge weakness — a single webpage or a single version of an image will be the main reference point for knowing why a meme came to be, and the lifespan of these references are short indeed. Even when hosted at prominent hosting sites or as part of a larger established site, one good housecleaning or consolidation will shut off access to the information, possibly forever.

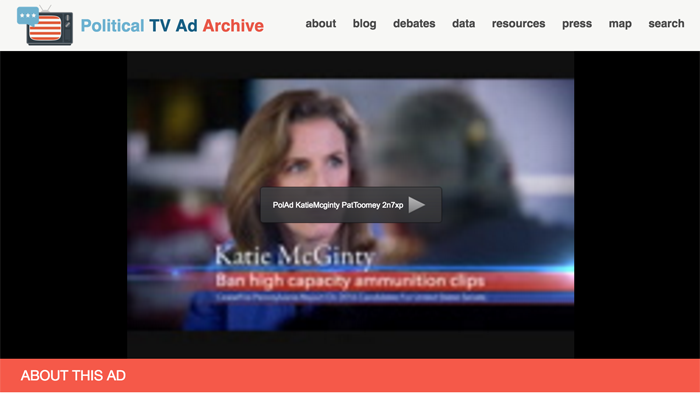

This is where the Internet Archive comes in. With our hundreds of billions of saved URLs from 20 years stored in the Wayback Machine, a neutral storehouse of not just the inspirations for memes but examples of the memes themselves are kept safe for retrieval beyond the fleeting fads and whims of the present.

The metaphor of “the web” turns out to be more and more apt as time goes on — like spider webs, they’re both surprisingly strong, but also can be unexpectedly lost in an instant. Connections that seemed immutable and everlasting will drop off the face of the earth at the drop of a hat (or a server, or an unpaid hosting bill).

Memes are, as I said, compressed culture. And when you lose culture, you lose context and meaning to the words and thoughts that came before. The Wayback machine will be a part of ensuring they stick around for a long time to come.

Mnemosyne was the Greek muse who personified memory. She was a Titaness who was the daughter of Uranus (who represented “Sky”), the son and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth. When you break it down, Mnemosyne had a deeply complicated life, and ended up birthing the other muses with her nephew, Zeus. Ancient Greek myth was quite an incestuous place, and every deity had complicated and deeply interwoven histories that added layers and layers of what we would now call “intertextuality.” Look at it this way: a Titaness, Mnemosyne, gave birth to Urania (Muse of Astronomy), Polyhymnia (Muse of hymns,) Melpomene (Muse of tragedy,) Erato (Muse of lyric poetry,) Clio (Muse of history,) Calliope (Muse of epic poetry,) Terpsichore (Muse of dance,) and Euterpe (Muse of music). It’s complicated. Mnemosyne also presided over her own pool in Hades as a counterpoint to the river Lethe, where the dead went to drink to forget their previous life. If you wanted to remember things, you went to Mnemosyne’s pool instead. You had to be clever enough to find it. Otherwise, you’d end up crossing the river under the control of spirits guided by the “helmsman” whose title translates from the Greek term “kybernētēs” across the mythical river into the land of the dead aka Hades. What’s amazing about the wildly “recombinant” logic of this cast of characters is that somehow it became the foundation of our modern methods for naming almost every aspect of digital media — including the term “media.” Media, like the term data is a plural form of a word “appropriated” directly from Latin. But the eerie resonance it has with our era comes into play when we think of the ways “the archive” acts as a downright uncanny reflection site of language and its collision between code and culture.

Mnemosyne was the Greek muse who personified memory. She was a Titaness who was the daughter of Uranus (who represented “Sky”), the son and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth. When you break it down, Mnemosyne had a deeply complicated life, and ended up birthing the other muses with her nephew, Zeus. Ancient Greek myth was quite an incestuous place, and every deity had complicated and deeply interwoven histories that added layers and layers of what we would now call “intertextuality.” Look at it this way: a Titaness, Mnemosyne, gave birth to Urania (Muse of Astronomy), Polyhymnia (Muse of hymns,) Melpomene (Muse of tragedy,) Erato (Muse of lyric poetry,) Clio (Muse of history,) Calliope (Muse of epic poetry,) Terpsichore (Muse of dance,) and Euterpe (Muse of music). It’s complicated. Mnemosyne also presided over her own pool in Hades as a counterpoint to the river Lethe, where the dead went to drink to forget their previous life. If you wanted to remember things, you went to Mnemosyne’s pool instead. You had to be clever enough to find it. Otherwise, you’d end up crossing the river under the control of spirits guided by the “helmsman” whose title translates from the Greek term “kybernētēs” across the mythical river into the land of the dead aka Hades. What’s amazing about the wildly “recombinant” logic of this cast of characters is that somehow it became the foundation of our modern methods for naming almost every aspect of digital media — including the term “media.” Media, like the term data is a plural form of a word “appropriated” directly from Latin. But the eerie resonance it has with our era comes into play when we think of the ways “the archive” acts as a downright uncanny reflection site of language and its collision between code and culture. Until the internet, the term cyber was usually used to measure words about governance and then later evolved to how we look at computers, computer networks, and now things like augmented reality and virtual reality. The term traces back to the word cybernetics, which was popularized by the renowned mathematician Norbert Wiener, founder of Information theory, at MIT. There’s a strange emergent logic that connects the dots here: permutation, wordplay, and above all, the use of borrowed motifs and ahistorical connections between utterly unassociated material. I guess William S. Burroughs was right: the world has become a mega-Cybertron, a place where everything is mixed, cut and paste style, to make new meanings from old. With people like Norbert Wiener, cybernetics usually refers to the study of mechanical and electronic systems designed at heart, to replace human systems. The term “cyberspace” was coined by William Gibson, to reflect the etherealized world of his 1982 classic, Burning Chrome. He used it again as a reference point for Neuromancer, his groundbreaking novel. A great, oft-cited passage gives you a sense how resonant it is with our current time:

Until the internet, the term cyber was usually used to measure words about governance and then later evolved to how we look at computers, computer networks, and now things like augmented reality and virtual reality. The term traces back to the word cybernetics, which was popularized by the renowned mathematician Norbert Wiener, founder of Information theory, at MIT. There’s a strange emergent logic that connects the dots here: permutation, wordplay, and above all, the use of borrowed motifs and ahistorical connections between utterly unassociated material. I guess William S. Burroughs was right: the world has become a mega-Cybertron, a place where everything is mixed, cut and paste style, to make new meanings from old. With people like Norbert Wiener, cybernetics usually refers to the study of mechanical and electronic systems designed at heart, to replace human systems. The term “cyberspace” was coined by William Gibson, to reflect the etherealized world of his 1982 classic, Burning Chrome. He used it again as a reference point for Neuromancer, his groundbreaking novel. A great, oft-cited passage gives you a sense how resonant it is with our current time:

J Spooky’s work ranges from creating the first DJ app to producing an impactful DVD anthology about the “Pioneers of African American Cinema.” According to a

J Spooky’s work ranges from creating the first DJ app to producing an impactful DVD anthology about the “Pioneers of African American Cinema.” According to a

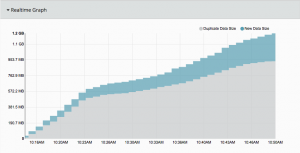

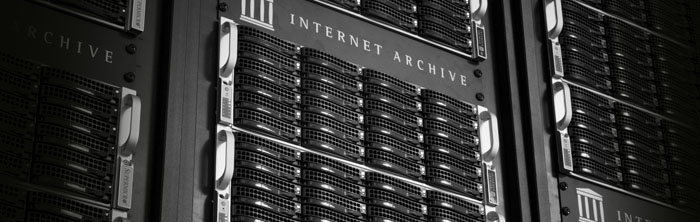

Our data mirroring scheme ensures that information stored on any specific disk, on a specific node, and in a specific rack is replicated to another disk of the same capacity, in the same relative slot, and in the same relative datanode in a another rack usually in another datacenter. In other words, data stored on drive 07 of datanode 5 of rack 12 of Internet Archive datacenter 6 (fully identified as ia601205-07) has the same information stored in datacenter 8 (ia8) at ia801205-07. This organization and naming scheme keeps tracking and monitoring 20,000 drives with a small team manageable.

Our data mirroring scheme ensures that information stored on any specific disk, on a specific node, and in a specific rack is replicated to another disk of the same capacity, in the same relative slot, and in the same relative datanode in a another rack usually in another datacenter. In other words, data stored on drive 07 of datanode 5 of rack 12 of Internet Archive datacenter 6 (fully identified as ia601205-07) has the same information stored in datacenter 8 (ia8) at ia801205-07. This organization and naming scheme keeps tracking and monitoring 20,000 drives with a small team manageable.