By Paul Soulellis

We usually think about archives as places of abundance. Deep, rich sites that house a multitude of perspectives. This can certainly be true, but archives are also sites of erasure, allowing some voices or perspectives to be minimized and excluded when they don’t fit into normative narratives.

Traditionally, stories involving people of color, queer people, and other historically-marginalized voices have been left out of archives, or diminished, because of ignorance, homophobia, and racism. Histories aren’t “discovered” in archives; rather, we use archives to actively construct versions of history, stories that accommodate our own subjective positions and ideologies. All too frequently, these stories favor the familiar structures of oppressive power—whiteness, patriarchy, and capitalism.

Likewise, the public domain is a remarkable construction that allows us to define who is or isn’t included in normative narratives. The public domain proclaims certain material as property owned by no one; cultural material in the public domain, theoretically, belongs to everyone. As copyright law enables new content to enter the public domain each year, it’s important to look closely at which voices are amplified in the celebration of open culture. There is no actual public domain. There is no site or territory or designation that reflects an authentic condition of “making public.”

Rather, it’s a complex, evolving structure defined by the institutions that serve as portals to cultural material—museums, libraries, courts, and archives like this one. They carry a responsibility to give (or deny) access to materials that traverse in and out of the public domain. But as an institutional construct, the public domain can easily fail to reflect any true nature of “the public;” without careful consideration, access to the public domain ends up repeating and perpetuating, in a highly predictable way, the same oppressive structures that govern society and culture.

What can be done? It’s crucial that we carefully examine our archives and search for lost voices, stories of failure, non-linear trajectories, and other non-conventional perspectives. We must refuse to accept traditional timelines at face value, and work to amplify marginalized material that has otherwise gone unnoticed, or erased. When confronting an archive or any presentation of historic cultural material, it’s irresponsible not to ask urgent questions like: What forces shaped this? Who was excluded? Who else should be included here in order to better understand the material at hand? Once engaged, we can actively work to change the shape of history, giving it dimension and depth and greater representation for all who were involved. This is what I’ve been calling queer archive work.

I’m really grateful to the Internet Archive for inviting me to help shape their effort to present newly available material in the public domain. During my residency here, for the last 3 weeks, I’ve been searching archive.org for forgotten material — in particular, evidence of African-American culture, Native American culture, early LGBTQ voices, and other artifacts from 1923 that in the past would have been forgotten or actively left out of celebrations of open access culture. If something seemed to be missing, I tried to find it elsewhere and upload it to archive.org. Remarkably, I found the first openly lesbian book of poetry ever published in North America, On A Grey Thread, by the Bay-area poet Elsa Gidlow, from 1923. It had never been digitized, but a PDF from the author’s estate was sent to me for this project and is now online, as of a few days ago.

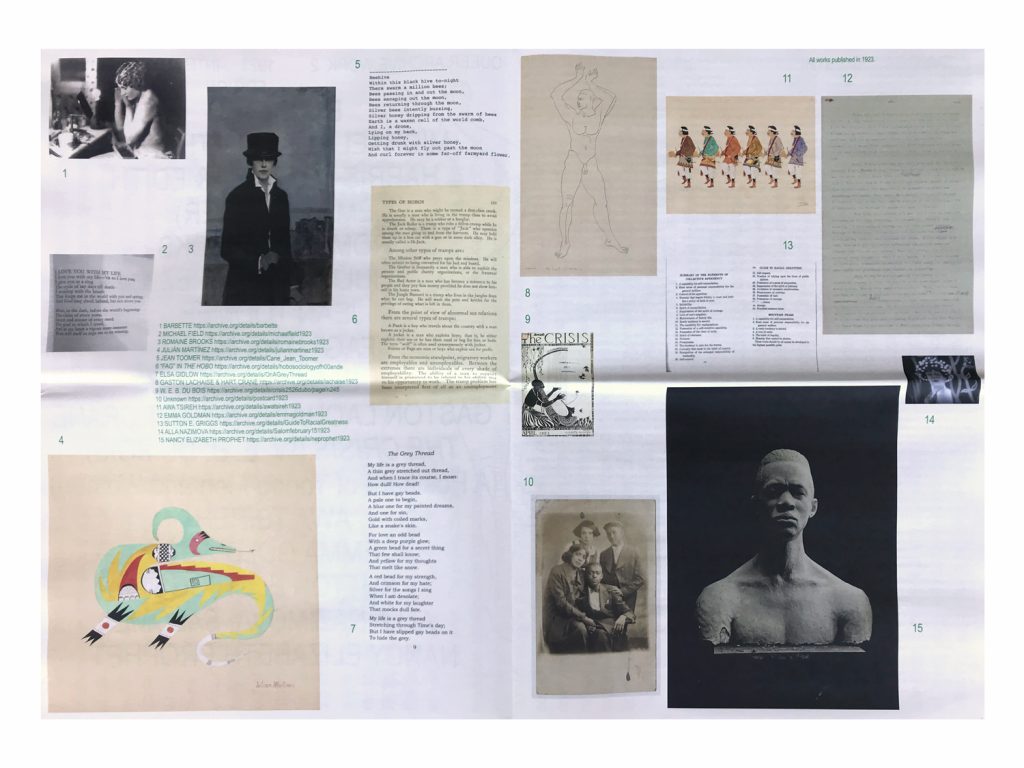

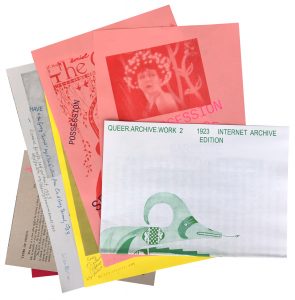

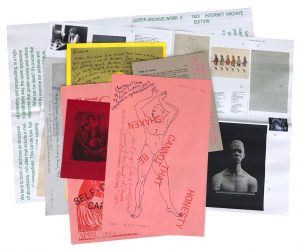

The result is QUEER.ARCHIVE.WORK 2, 1923 INTERNET ARCHIVE EDITION. It’s an edition of 100 copies that I edited, designed, and printed myself at a small press in Berkeley, and it features 15 lesser-known historical artifacts. All of it is now available on archive.org. I’m very proud that the Internet Archive enabled me to create this project. By bringing these items together in a loose assemblage, in the form of a publication, my hope is to create a place for forgotten voices to co-mingle. I think by doing more of this work, we can challenge what we think or assume we know about the early years of the 20th century, and imagine other kinds of histories.

For more see:

http://soulellis.com

http://queer.archive.work

https://queer.archive.work/2/index.html

https://archive.org/details/soulellis

It’s such a good thing that the internet archive exists, right?

I would really thank you to Brewster Kahle for the hard work making this. Keep up the good work preserving content

I’m so glad that this exists. I look forward to my students finding this when they explore the site for their Public Domain project.

Brewster you brought me back to the libraries.

The love of books renewed, which was 30 years afar.

Of course the variety has changed from fiction to others.

Thanks to the team with you.

Pingback: Conference report: A Grand Re-Opening of the Public Domain - Hanging Together