This is a guest post by Lawrence Wilkinson and Richard Whitt summarizing a conversation they led at the 2018 Decentralized Web Summit on the topic of the language and terminology we use to talk about the Decentralized Web.

“What do we mean exactly by X?”

As the conversation around the Decentralized Web has evolved, one persistent line of questions has been around the very definition of language we commonly use.

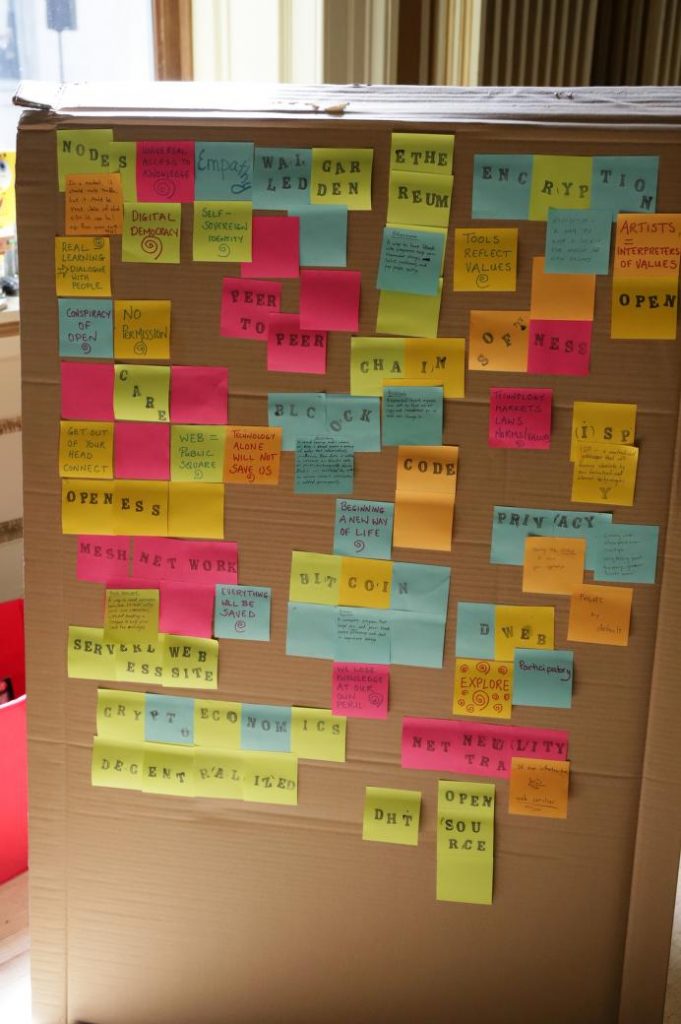

Over the course of the Builder’s Day, and the two days of the Decentralized Web Summit 2018, a group came together to parse this shared language. The terms “decentralized,” “federated,” and, perhaps especially, “open,” amongst others, were proffered for conversation, and the participants provided some excellent input.

The goal was not to codify or limit ourselves. One discussant made the excellent point that some ambiguity is not a negative thing at this relatively early stage of development. It was labelled a “Goldilocks problem” — too much ambiguity, and there is a failure to communicate and difficulty to cooperation; too little ambiguity, and there is little room for experimentation and happy accidents. The point, shared by others, is that we should want just enough of a shared understanding to allow us to move forward together, but still retain enough ambiguity to allow for innovation.

The Right Questions

By and large, there was agreement that we cannot all agree on what various terms mean with great precision. For example, for some the concept of being “decentralized” was the endgame, a goal unto itself. The consensus seemed to be, however, that “decentralization” refers variously to resources, or to functions, or to governance, and that each of these connotations in turn was a means to a larger objective. By contrast, the term “openness” generally was seen as the end goal — the why — while decentralized systems and protocols are the tools, the means — the how.

When the several groups worked through the nuances, there appeared to be some agreement on the following set of categories based upon a specific line of questions that were being asked: in essence, what role is the particular term or concept intended to serve?

What

- Web, Internet, Network, Protocol, Application, Blockchain, Server, End Point, Holographic Storage

How

- Decentralized, Distributed, Federated, Interoperable, Self-steering, Generative tensions, Immune system response, Communication

Who

- Users, Communities, Governance, Community-Governed, Builders, Founders, Ecosystem

Why/To What Effect/To What End

- Privacy, Security, Open, Agency, Trust, Sustainable, Scalable, Global Consensus, Alignment, Provenance, Permissionless, Same opportunity for everyone, Tyranny, Manipulation, Stalked, Facts, Competitive with Centralized Systems, Who Loses, Self-Sovereign Data, User-Controlled, Effects on/For Users, Risks of Current Situation, Unrealized Benefits

“Constructive Conflict” as a Feature, Not a Bug

Our glossary of terms, once our group established roughly which question a given term sought to answer, took a fascinating turn from trying to precisely define each term to doubling down on our shared sense that, at present, definitional confusion or fuzziness was less a bug and more a feature.

As the Decentralized Web endeavor matures into a field, the terminology will settled into firmer and more widely-accepted definitions. But in the meantime, such perspective creates a “space” in which different understandings of a term can generate constructive conflict and lead to surprising advances.

Ambiguity, in this instance, is the friend of creativity, encouraging questioning, learning, and innovation. And at this stage in the development of the D Web, creation is the main event.

EDITORS NOTE: We will continue to wrestles with these issues at DWeb Camp, July 18-21, 2019. We hope you will join us.

Lawrence Wilkinson Wilkinson is Chairman of Heminge & Condell (H&C), an investment and strategic advisory firm. Through H&C, Lawrence is involved in venture formation work, and as a director and counselor to a number of companies that he helped create over the years, among them: Wired, Oxygen Media, Broderbund Software, Ealing Studios, Colossal Pictures/USFX, Design Within Reach, and Public Bikes. As co-founder and president of Global Business Network (GBN), Lawrence helped develop and spread the scenario planning approach to long-term planning, now one of the most widely-used techniques by organizations globally; he continues to offer strategic counsel to a number of corporate clients, NGOs, and governments around the world. His recent work includes leading strategy projects for The Internet Archive, Mozilla, Wikimedia, EFF, Code for America, KQED, and Public Radio (NPR/PRI/CPB), all focused on the Future of Civil Discourse. He serves as Chair of The Institute for the Future (IFTF), Vice-Chair of Common Sense Media (which he co-founded), and a director of Landesa, Public Radio International, Public Architecture, and The Global Lives Project; as an advisor to The Library of the Future Project at The Bodleian Library, Oxford; as a Visitor at Harvard University Libraries; and as a Fellow of the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics. He is a graduate of Davidson College, Oxford University, and Harvard Business School.

Richard Whitt Whitt is an experienced corporate strategist and technology policy attorney. Currently he serves as Fellow in Residence with the Mozilla Foundation, and Senior Fellow with the Georgetown Institute for Technology Law and Policy. As head of NetsEdge LLC, he advises companies on the complex governance challenges at the intersection of market, technology, and policy systems. He is also president of the GLIA Foundation, and founder of the GLIAnet Project.

Richard is an eleven-year veteran of Google (2007-2018). Most recently he served as Google’s corporate director for strategic initiatives, working with Vint Cerf, Hal Varian, and other Googlers on policy and ethical issues related to Internet of Things, machine learning, broadband connectivity, digital preservation, and other emerging technologies. A notable achievement was negotiating successfully with the Cuban government for permission to build the country’s first free public WiFi hotspot for Internet access. From 2012 to 2014, Richard was chosen by Google management as the Corporate Vice President and Global Head of Public Policy at newly-acquired Motorola Mobility.

Prior to his executive role with Motorola, Richard served as Google’s director and managing counsel for federal policy, overseeing strategic thinking on privacy, cybersecurity, intellectual property, Internet governance, and free expression. Previously he led the Company’s substantive advocacy on issues such as network neutrality, broadband deployment, “unregulation” of Internet applications, and spectrum policy. In particular he headed up Google’s open Internet policy on a global basis, guided the Company’s participation in the FCC’s 700 MHz auction, helped secure TV White Spaces spectrum allocation, and collaborated on the nationwide launch of Google Fiber.

Before joining Google in 2007, Richard spent twelve years in the legal department at MCI Communications. He most recently headed up MCI’s DC office as vice president for federal law and policy.

intersting. Useful post for me. thank you

Hello to all, because I am genuinely keen of reading this webpage’s post

to be updated regularly. It consists of pleasant data.

Thank You for share great information…

Hi all. I am new guy here. Hope to be friend with all

Very interesting! More people should know about this!

Thanks for share this…

Thank You for share great information…

thanks