This is the third in a series of guest blog posts exploring the real-world implications of the Decentralized Web Principles.

By Kelsey Breseman

Kelsey Breseman is a Rita Allen Civic Science Fellow at the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative, where she works on environmental accountability, data ownership models, and intentional community. Kelsey has founded and managed tech startups, and has a history of activist leadership for progressive causes. She has a B.S. in Neural Engineering from Olin College and is currently working on a M.S. in Data Science from UT Austin.

I originally entered the decentralized web space through a problem with trust and power. I’m a member of the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative (EDGI), an organization that sprang up in the wake of the Trump administration in an effort to prevent a climate-denialist administration from reducing public access to critical government-held data about the environment. In the EDGI working group then called Archiving, we were looking at ways to back up datasets such that scientists would be able to use them as proof — implying a strong chain of provenance — even if the original source were to remove access.

The question was, how could we ensure that data for the protection of the environment was owned by the people in a trustworthy way? The decentralized web offered broad distribution and a blockchain-backed provenance. So the decentralized web can — at least theoretically — help to protect the environment through the preservation of critical data.

But oft-cited statistics show Bitcoin proof-of-work transactions use energy at rates higher than some nations. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which made headlines as they exploded in use in the digital art market, similarly nudge our already beleaguered climate further toward apocalypse (this was discussed at the DWeb meetup this past May). Regardless of whether you see the projections as overblown or realistic, it is certainly true that, as with any new and growing tech, there is significant energy use from decentralization technology.

The basic pattern is the same across the technologies: proof-of-work is an inherently and intentionally energy-inefficient process that is the basis for Bitcoin’s stability as a currency; as the value of the currency rises, mining (which performs the energy-intensive proof-of-work process) becomes financially incentivized; high energy consumption increases carbon emissions, oil and coal extraction and burning, and so on. And so, decentralized web technology contributes to the destruction of habitability on our planet. Most articles you’ll find about this discuss cryptocurrency and NFTs, but our use case of decentralized and highly duplicated file storage isn’t immune. Aren’t we asking for more files to be stored on more servers, with more aggregate uptime and thus more energy use?

In this context, do we now need to protect the environment more directly from the decentralized web?

The Decentralized Web principles released earlier this year by the Internet Archive, DWeb Nodes, and other members of the Decentralized Web community include:

Ecological Awareness

- We believe projects should aim to minimize ecological harm and avoid technologies that worsen environmental health.

- We value systems that work towards reducing energy consumption and device resource requirements, while increasing device lifespan by allowing repair, recycling, and recovery.

Though this principle could apply equally to any project — of course we should minimize ecological harm — it’s worth a brief exploration of the implications in the decentralized web space.

Energy use is an acknowledged issue with the decentralized web, and especially decentralized ledger (cryptocurrency) technologies, so there is a fair amount of writing in this space. Here, I’ll break down the most common takes I’ve seen folks bring up to address the ecological (usually energy-centric) impacts of this tech:

Carbon-Neutralize the Approach

This is the idea that the high energy use of decentralized web technologies is okay as long as you make sure the energy comes from renewable resources. In practice, this looks like the Renewable Energy Buyers Alliance, the Crypto Climate Accord, or the Energy Web Foundation: leveraging the collective power of energy users to create a demand for low-carbon energy that triggers a transition of the grid to renewable infrastructure. You’ll often see the phrase “net zero” — we’ll emit carbon, but then try to balance it out.

Transition to renewables is absolutely necessary, but as an answer to high energy use, it falls short. In grid-level discussions of renewable energy adoption, we see a lot of celebration that renewables are a growing percentage of our energy source. For example, U.S. states set “renewable portfolio standards” (RPS) defining a percent-renewable energy source for their grid infrastructure, and it’s fairly common for states to exceed their targets. California, for example, had a goal of 33% renewables by 2020 which they had already exceeded by 2018.

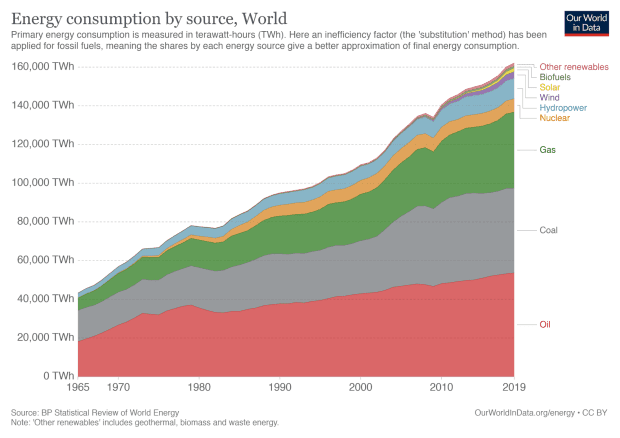

What often gets passed over however, is that year over year, energy demand grows so much that this typically means a growth across all sectors of energy generation, from solar to coal. What we’re celebrating, then, is not a displacement of coal/actual reduction in carbon emissions, but that new demand is being covered by proportionally more renewable sources than we’re used to.

Growth in global energy demand, from BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy showing a general trend of growth across all sectors, including coal — even as renewables grow disproportionately.

And of course, even renewable infrastructure has an ecological cost (e.g. materials extraction) — so though decarbonization of our energy infrastructure is an important objective, any proposed solution that doesn’t attempt to decrease energy demand is underwhelming.

Try Something with Less Energy

As mentioned above, cryptocurrencies traditionally rely on energy-intensive proof-of-work as a mechanism for stability. Like the gold standard, the currency works because it is difficult to obtain, and increasingly so over time. Also like the gold standard, it’s something we may have the choice to move on from, hopefully in ways that serve our values.

The most famous foray into this change is proof-of-stake. Proof-of-work relies upon calculations that increase in complexity as the blockchain grows, requiring miners to purchase hardware and electricity as a cost of mining. Proof-of-stake is a more direct form of reinvestment; it ties up a miner’s existing coins as stake against the transaction.

Proof-of-stake is most touted for its much lower energy profile than proof-of-work. Altcoin uses it; Ethereum is switching to it; Bitcoin may or may not ever make that transition. These choices tend to be values-based. Proof-of-work’s original claim to fame was as a solution to the problem of double spending, where the same coins could be spent twice, destroying the integrity of the currency. Adherents to proof-of-work over proof-of-stake cite the importance of Bitcoin’s long-running stability across years of worldwide usage. Proof-of-stake is newer and less widespread; it’s impossible to declare it equally reliable yet, though it seems plausible that it might be. If so, the energy reduction would be worthwhile.

Make a Judgment Based on Values and Worth

Rather than asking in isolation how much carbon emissions decentralized web technologies create, many re-frame to draw a baseline. They ask, how do emissions from cryptocurrencies compare to emissions from traditional banking?

I haven’t come across a truly excellent breakdown of ecological cost for cryptocurrencies versus centralized banking, or even a hint of an attempt to compare emissions per dollar equivalent. However, there does exist some good comparative discussion, both of the costs of the two industries and of the value they provide (here’s an article from NASDAQ, for example).

I’m pleased to see the discussion. Cryptocurrencies are in many ways a practical protest against the power and control of traditional banks and government control. If the aim is to disrupt and displace, it’s important to compare the impacts of the two industries.

There’s much to critique in traditional banking. Quite apart from the ecological costs of day-to-day business, fossil fuel divestment has been a critical strategy of the climate movement, whether at the university endowment level or the personal ask to stop using Wells Fargo in response to their financial involvement in the Dakota Access Pipeline. People argue from both ecological and justice perspectives that disruption of traditional banking is a net positive. Others accept the ecological cost of decentralized finance tech as worthwhile, even if only for the trust and security of a chain of provenance.

When we create something new, we hope to make a meaningful improvement. We hope at worst that the cost of our prototype yields something worthwhile: an important learning. It should encapsulate a way of thinking that is different, in some critical way, from what exists. I remain attracted to the decentralized web space because I see so many people in it who are both thoughtful and taking action. People are reading books about power, about money, about justice, and making new protocols — both technical and human — that seem like they could fundamentally change the way our world works, and the way we work together within it.

But how can you know what is a sci-fi fantasy and what is grounded truth? As an expatriate of the Silicon Valley tech world, I know how easy it can be to get embroiled in the pitch: working so hard to earnestly convey that your startup is the key to changing the world. It’s a machismo-filled drive to oversell in order to stand out, to raise your VC seed, such that you yourself become over-convinced that the niche technology you’re developing is the one true way to save the world.

Take a second. Breathe. Think about busyness as a tool of oppression: the urgency that keeps you from ascertaining the full truth, taking the time to determine which systems are most in need of dismantlement. I know, I’m a radical; this is our language. But from what I’ve seen, most people get into DWeb for reasons that are at root more political than technological: you want some kind of change, some kind of power to people (decentralization), some kind of accountability (blockchain) and some way to claim identity-centric control (crypto). Admitting that, it’s not too much more radical to double-check the theory of change: do our technologies really serve the goods they claim to? How, and how can we ensure they do?

The DWeb principle at hand doesn’t make a value judgment with respect to energy use; its entreaty is awareness. It takes conscious work to think through the potential impacts of your (technical) choices, and I would ask that of you: slow down. Think it through. Make a decision about worth and value, rather than letting the flash and urgency of innovation sweep through you. The only way to know is to take the time to find out.

Nice