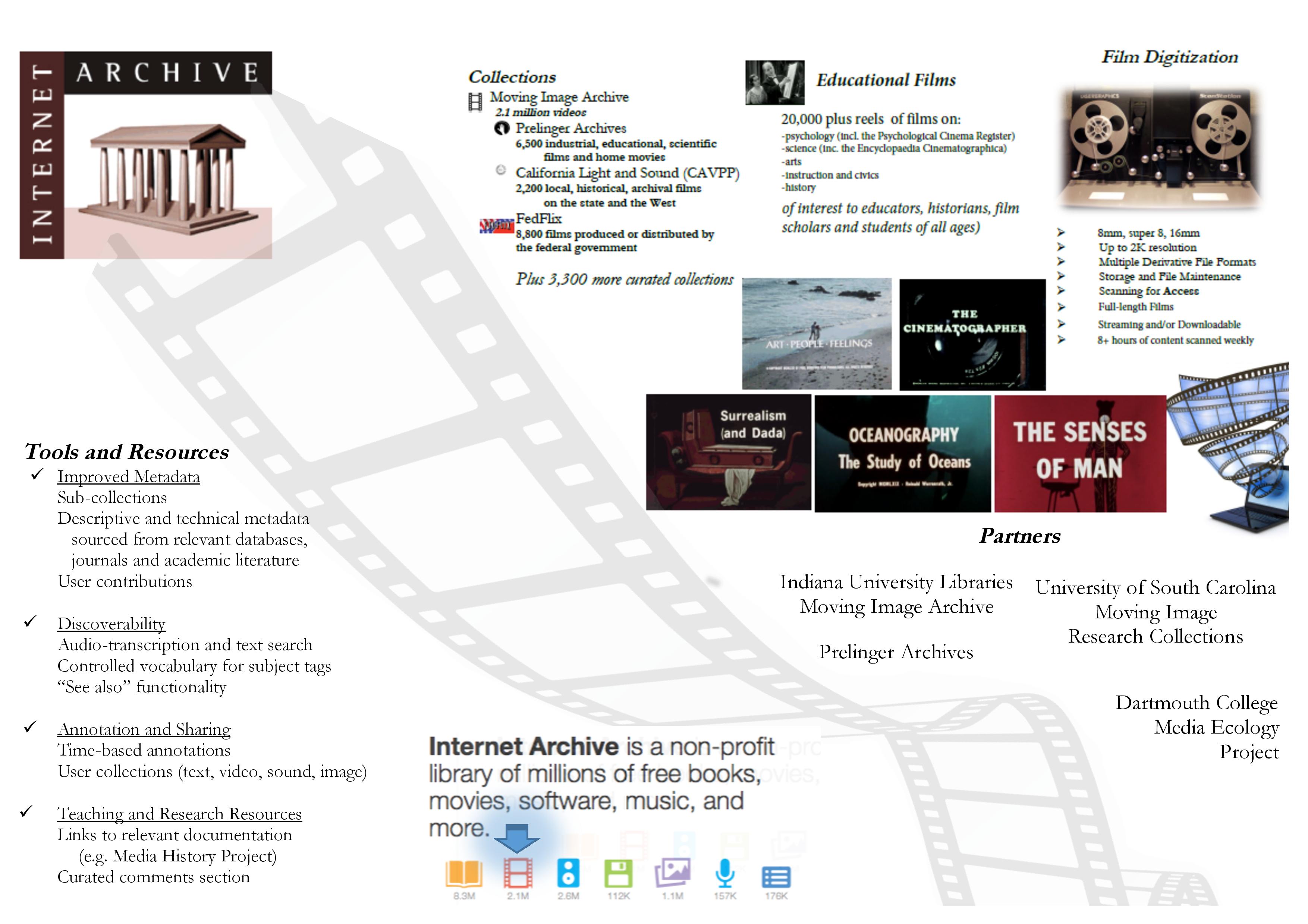

The Internet Archive is actively engaged in digitizing a wide variety of educational films on science, education, the arts, psychology, medicine and history. In this new blog series, we will highlight films that are newly digitized and available each week on the collection page, to provide visitors with a better idea of the breadth and depth of this quirky, informative and much-in-need-of-preservation medium: the non-theatrical film.

First up is Film Firsts a documentary in two parts (Part 1 and Part 2) covering the early history and development of the medium of motion pictures.

Our collection is rich in films about the film medium itself, whether aspects of its production (e.g. Cinematographer) or its history (e.g. Hollywood: The Golden Years and Hollywood the Dream Factory). Film Firsts, however, focuses on the early part of cinema’s developed the period usually described as early and silent cinema.

Produced for television audiences (ABC) but also screened for school groups and other non-theatrical audiences, the two-part, hour-long documentary does not exactly amount to a thorough and unbiased history but it is very representative of this reflexive sub-genre that dealt with the evolution of the motion picture. Often such films catered to the audience’s nostalgia in an era where memories of the nickelodeon and the picture palace were very much alive. They also provided a venue for studios to repurpose their library of films for the era of television. Finally, in a more implicit manner, they partook in an evolutionary rhetoric that cast the turn-of-the-century flickers as a primitive manifestation of an art and industry that by the 1950s and 60s had blossomed into a global entertainment empire.

While film historians have long pointed out the fallacy in such reasoning, it is still useful to consider these compilation/history documentaries for the narrative of film’s development that they provide, the moments along this trajectory that they choose to highlight and, just as important, what they obscure or gloss over.

Film Firsts has references to all the usual highlights: Edison’s Black Maria studio, Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, Melies’ Trip to the Moon, as well as a substantial section on early Westerns. This reflects the origins of the project in director Paul Killiam’s “Movie Museum” talks covering “films of historical interest illustrated by clips of vintage 1895 to 1915.” Many similar compilation films started as programs of the lecture circuit, reflecting a significant practice of the non-theatrical market.

Focusing on well-known “screen personalities” like Bronco Billy Anderson, but also delving into more idiosyncratic, behind-the-scenes aspects of the art and craft of moviemaking like special effects and animation, Killam compiles a list of “bests” and “firsts”: the first close-up, the first kiss, the first cartoon, the first western, the first use of lighting for effect, etc. Although, even with the resources that historians and archivists have today it is always perilous to claim any single example of an effect, practice or technique as “the first” of its kind, the authoritative voice of the documentary accurately represents an early vein of film historiography (see also works by Terry Ramsay and Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach in the same period). As the medium was entering its second half-century of life, it was taking stock of pioneers, sentimentally remembering great moments and stars of the past, and “leafing” through its own history, as one might leaf through an old scrapbook or album of photographs.

Film Firsts thus represents this early “scrapbook” phase of historiography, crucial in that it was conducted by the medium itself in an era where it’s viability was threatened by the popularity of television — which is here deployed in the service of the older medium. It was actually the first episode in a six-part series entitled “Silents Please! The History of the Motion Picture” that promised an overview of “the stars, thrills, laughter and heartbreak” of silent cinema. Whether a nostalgic look on a much-evolved medium, a semi-authoritative account of the people and technology that made the motion picture possible or a potpourri of clips and firsts for the consumption a television audience, the film is a valuable document of historiography in practice and as such a valuable addition to our collection covering the history of educational audiovisual media.

For more information on the film see:

http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1998-06-25/features/9806250371_1_silent-film-silent-era-killiam-collection

Dimitrios Latsis

CLIR-Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Data Curation for the Visual Studies, Internet Archive.