A little behind the scenes here at the Archive: this blog is the province of a wide range of sub-groups, from books and partnerships over to development and collaborators. There’s usually a little traffic jam to schedule or make sure entries don’t go over each other, so this “sequel” post is being written before we return you to other Archive news.

The big announcement last week about the Internet Archive hosting Flash animations/games and making them run in the browser thanks to the Emularity and Ruffle made a huge splash. If you haven’t read that entry, you should definitely read it first.

Here’s some observations about Flash and the Internet Ecosystem from the last three rambunctious days. Obviously, the story of us including Flash doesn’t end here – we’ll continue to update Ruffle as it improves, and both users and collaborators are adding new animations at a pretty stunning clip. Be sure to keep checking the Flash Collection at the Archive for new additions.

What have we learned so far?

The Idea of Playing Flash in the Browser Past The End of The Year Is Very Popular

It was assumed, and has proven out, that being able to play Flash items, be they animations, toys or games, is an extremely popular idea: Tens of thousands of people have been flooding into the Archive to try things out. The “death” of Flash as a default plugin for browsers and the removal of easy access to it definitely had many people sad and concerned.

That said, assuming that Adobe and any other vendors were not going to throw the significant resources behind security and maintenance that Flash plugins would require, removing default support for it made sense. Sometimes these choices are not great for the historical Web, but sideloading in significant attack surfaces just because people like old games is not ideal either.

Ruffle is not Flash. It is an emulator that takes .SWF files (which worked with Flash) and makes a very good attempt to display what the file means to do. It is written in an entire other language with an entire other team of programmers, and is working with a specification and history that is ossified. In that way, it is hoped that the security issues of Flash can be avoided but the works can live on.

And are they living on!

Even in the very short time that this new feature has been announced, the news was picked up by Boing Boing, Engadget, The Verge, The Register, Gizmodo, PC Gamer, and dozens of other locations (and the top spot at Hacker News for a while). That increased the flood of visitors to our site and we’ve held up pretty well, due to the high compression rates and small file sizes of Flash.

People Have Very Strong Memories of Flash; For Some It Represents Childhood

Everyone has a different timeline with computers and the internet, but for countless people using their phones and connections today, Flash plays as critical a role in their childhood memories as a game console or television show. Students could sneak flash games into the computer labs, or trade USB sticks with Flash, or simply get around filters preventing “obvious” entertainment sites to find a single URL that gave them a racing or RPG game to while away an afternoon on.

And, most notably, not just as players, but as creators. There are, it turns out, a significant amount of professional artists and coders who count Flash and related technologies as their very first “programming language”. Going through our collection, you can find ten-person studio productions side-by-side a game made by a driven teenager at home, and the teenager will have gotten more popular. Intended to be used for creative works, the Flash environments over the years provided the launchpad for thousands of careers and creative outlets.

The Role of Flash Wasn’t Obvious To a Lot of People

An interesting situation as people come face to face with in some of these animations in the Flash collection are that many didn’t know they were Flash.

Video sites, such as Youtube, are a mid to late 2000s addition to the Internet. Previously, with dial-up modems as the main connection to the Internet, streaming video was a distant and hazy dream that seemed impossible to provide beyond a small experimental or well-connected crowd. Filling that need was Flash, which could compress down incredibly small (a full song and video to accompany it could be under five megabytes, or even one megabyte) and they even had quality settings for less powerful computers. Flash animation could “pre-load” the data required that was coming over a modem, giving an update as to progress or a small game to play, until the full “video” was downloaded. This has all been swept away into the dustbin of memory in a world where 4k 60fps video is possible (if still not to everyone).

With the jump to video in the mid 2000s, many Flash animations were transcoded into MPEG files, or animated GIFs, or uploaded to Youtube as fully-realized video, even though Flash was the original medium. As the more well-crafted works gained attention in this new space, the old formats were forgotten.

Since the Ruffle browser has a fullscreen option (right-click, soon to be a button to the right of the animation), if the Flash animation was done using vectors, they will scale up to 4k displays smoothly. Unlike old video, the original works will keep up with the newest technology very nicely and will give added appreciation for the efforts in the original piece.

Flooding All These Old Flash Works Has High and Low Moments

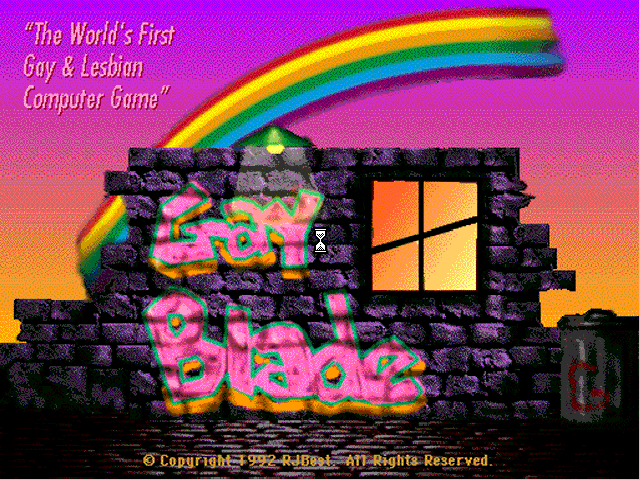

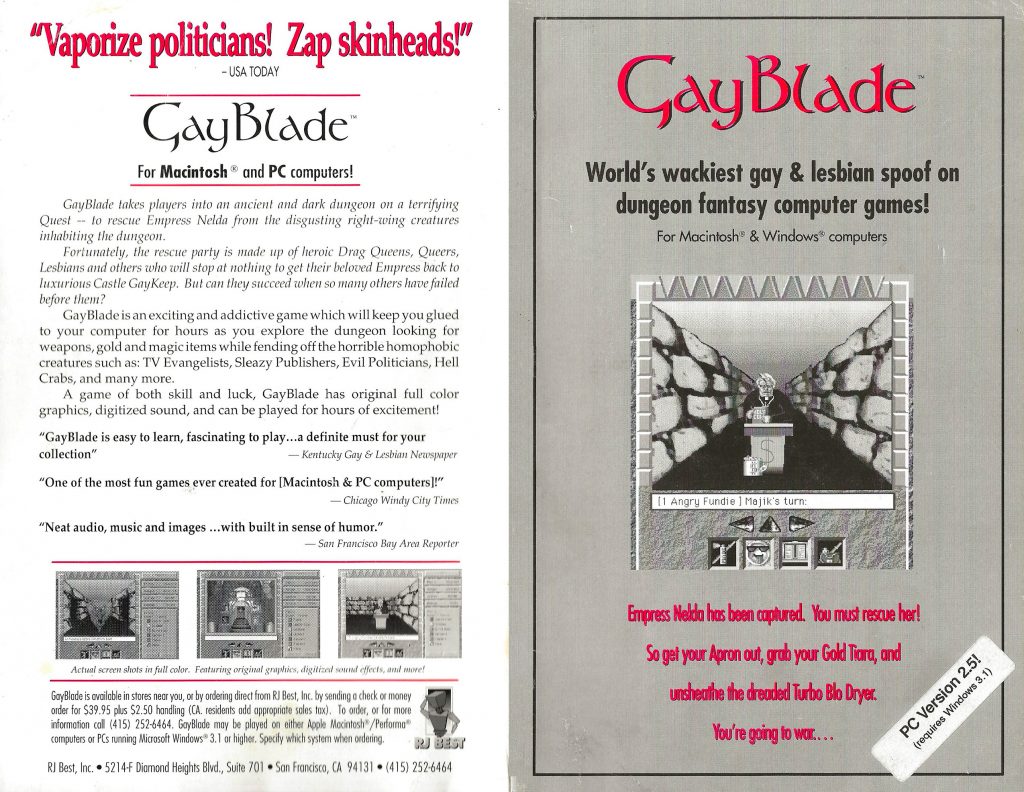

Because nearly anyone could create flash animations and games, nearly anyone did. It also meant that filters on quality, profanity, or unusual subjects were gone.

Sometimes that worked out very nicely: Imagine trying to pitch an animated film like The Ultimate Showdown of Ultimate Destiny to a studio or backers to make for film festivals. A game like Castle Cat is bizarre and a collage of pop culture but plays as well as a professional game at the time. (it even got a sequel.)

Other times, the works are clunky, poorly programmed, and full of offensive jokes and material. They could literally be after-school projects or whipped up in a weekend to make fun of someone or something and then get trapped in amber to the present day. Wandering the stacks, with what will soon be thousands of items, can be daunting.

As a result, the Showcase was created to highlight the best of the best, the handful that really universally stand out as entertaining, well-made, and uplifting (or at least, thought-provoking).

By the way, if the towering piles of Flash works seems daunting now, imagine what it was like 20 years ago for people slowly moving through page after page, taking minutes to download a given animation, and clicking on it with no idea what they’d be seeing next.

Adding Your Own Flash Is Difficult But Rewarding

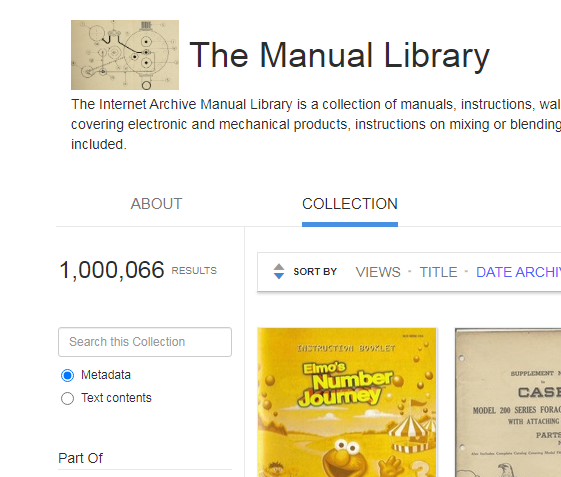

It is notably complicated to add new working Flash to our collection. This is a side effect of all the different components that need to be activated in the Internet Archive structure. By far, the best document to read about how to test, upload, and describe SWF files is this document by the Flashpoint project:

https://bluemaxima.org/flashpoint/datahub/Uploading_SWFs_for_the_Internet_Archive

(As a side note, the two most common mistakes are setting “emulator-ext” instead of “emulator_ext” (see the difference?) and not setting the item to be a “software” media type. A script has been written that checks new uploads to find common mistakes and will sometimes tweak the uploads to fix them.)

There’s Still A Long Way to Go To “Perfect” or Wayback Playback

We shoved this entire ecosystem into the Archive “hot”, with known gaps in support for Flash features, and with bugs still being ironed out. Most Flash animations used a rather small set of scripting commands within the potential list, and those have been focused on by the Ruffle team, so a lot of animations do just fine. But more than just a few times, a Flash item will go in and there will be a critical failure, be it the inability to hit buttons or missing video/audio. This reflects the continual improvement of the emulator but also that entire swaths of support are still a way to go.

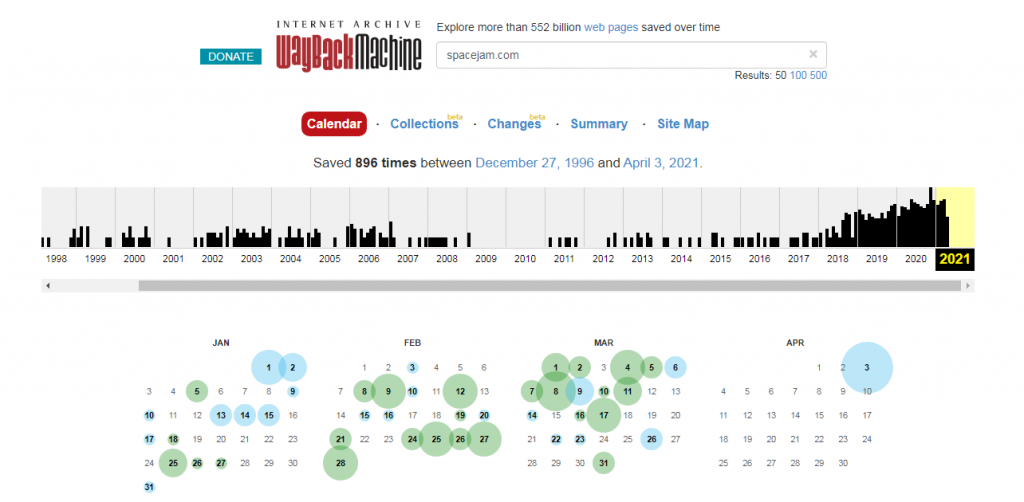

This also provides the answer to the question some are asking, which is how long before the Wayback Machine “just plays” old Flash items when you go to the page. Ruffle is still way too new to shove into the Wayback and the problems it would cause at this stage would be significant. Many improvements to Wayback and its reach have happened over the last year, with connections to Wikipedia, Cloudflare and Brave, but the day when you go to an old Flash-driven site and have it “just work” in Wayback is going to be a significant time in the future.

Which brings up another tangent:

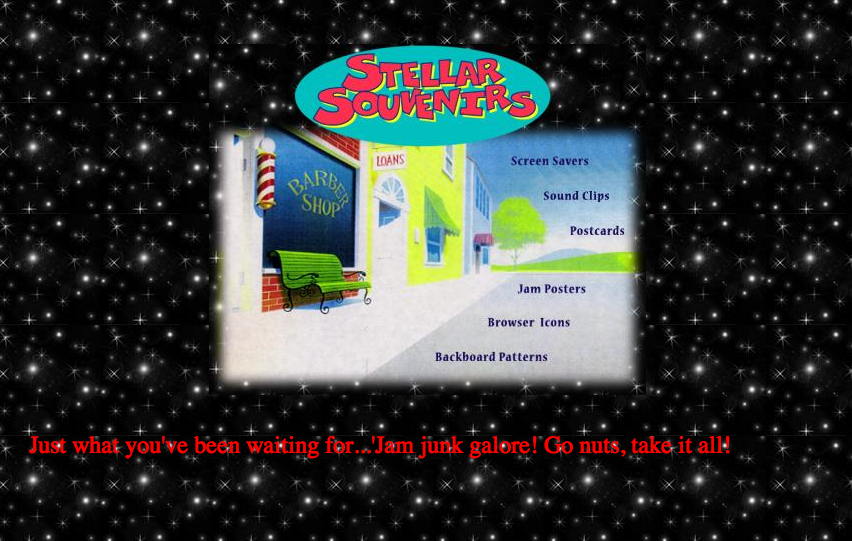

Flash Interfaces to the Web Were The Worst Idea

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s clear that the fad of making Flash boot up and be the “menu” or selections for a website were unusually cruel to anyone in need of portability or accessibility. What’s thought of as “Web 1.0” (HTML files and simple flat files provided to servers) was extremely good for screen readers and keyboard shortcuts, providing important access to blind or disabled users, as well as expanding the amount of devices and systems that could use the Web. Flash took a lot of that away in the name of.. well, Flashiness. As this small burst of interest in Flash has occurred, a not-insignificant amount of people dependent on accessibility have said “Good Riddance to Flash”, and they’re entirely right. Captured inside little boxes on Internet Archive as displays in a museum, they work fine enough. But the Web should never have depended on Flash for navigation.

When Flash Is At Its Best, There’s Nothing Like It On The Internet

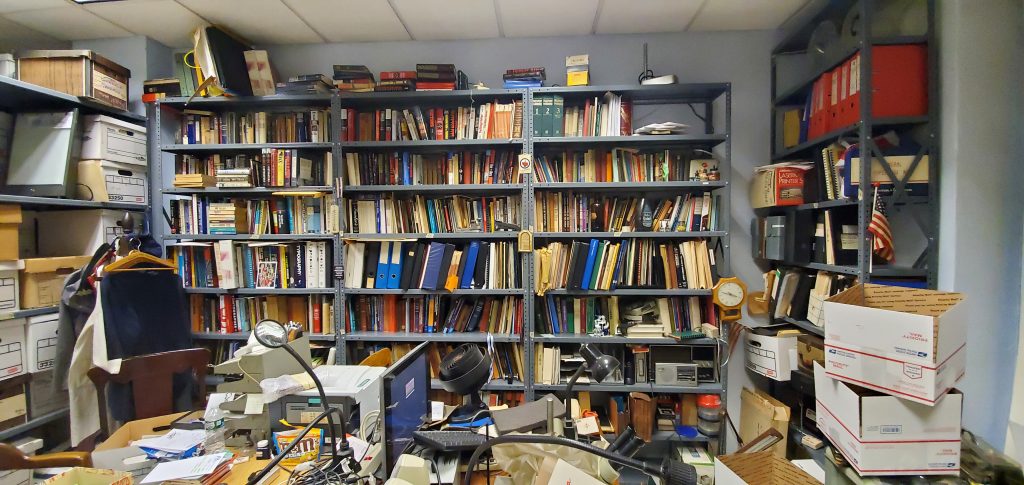

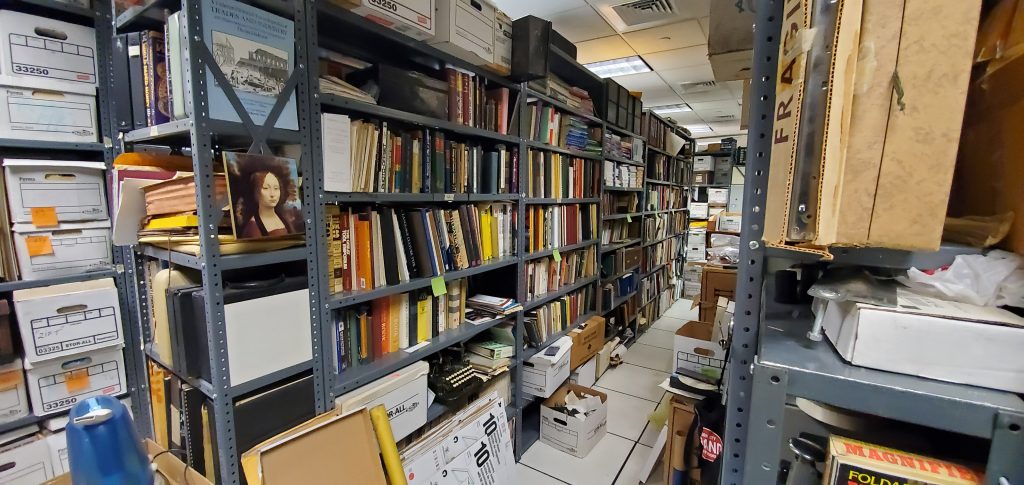

As people have been sharing the Flash animations they’ve found on the site, as well as providing their own additions, jewels have been coming to the forefront. Most inspiring have been artists and creators who did work 15 or 20 years ago and have been rifling through floppies and stored ZIP files to upload to our collection.

Watching this as they come in, it strikes us anew how much effort, artistic and otherwise, went into a good Flash animation. Crafting custom artwork, adding little touches and flair, and truly bringing something new into the world… this was the promise of Flash and every time someone in the modern age stumbles on a classic for the first time, all the effort is worth it.

Long Live Flash!

![[screenshot]](https://archive.org/serve/arcade_vliner/arcade_vliner_screenshot.png)

![[screenshot]](https://archive.org/serve/arcade_super21/arcade_super21_screenshot.png)

![[screenshot]](https://archive.org/serve/arcade_comg076/arcade_comg076_screenshot.png)

![[screenshot]](https://archive.org/serve/arcade_funcsino/arcade_funcsino_screenshot.png)

![[screenshot]](https://archive.org/serve/arcade_blkrhino/arcade_blkrhino_screenshot.png)

![[screenshot]](https://archive.org/serve/arcade_gnome_9/arcade_gnome_9_screenshot.png)