Our library is still strong, growing, and serving millions of patrons. But the publishers’ attack on basic library practices continues.

Last Friday, the Southern District of New York court issued its final order in Hachette v. Internet Archive, thus bringing the lower court proceedings to a close. We disagree with the court’s decision and intend to appeal. In the meantime, however, we will abide by the court’s injunction.

The lawsuit only concerns our book lending program. The injunction clarifies that the Publisher Plaintiffs will notify us of their commercially available books, and the Internet Archive will expeditiously remove them from lending. Additionally, Judge Koeltl also signed an order in favor of the Internet Archive, agreeing with our request that the injunction should only cover books available in electronic format, and not the publishers’ full catalog of books in print. Separately, we have come to agreement with the Association of American Publishers (AAP), the trade organization that coordinated the original lawsuit with the four publishers, that the AAP will not support further legal action against the Internet Archive for controlled digital lending if we follow the same takedown procedures for any AAP-member publisher.

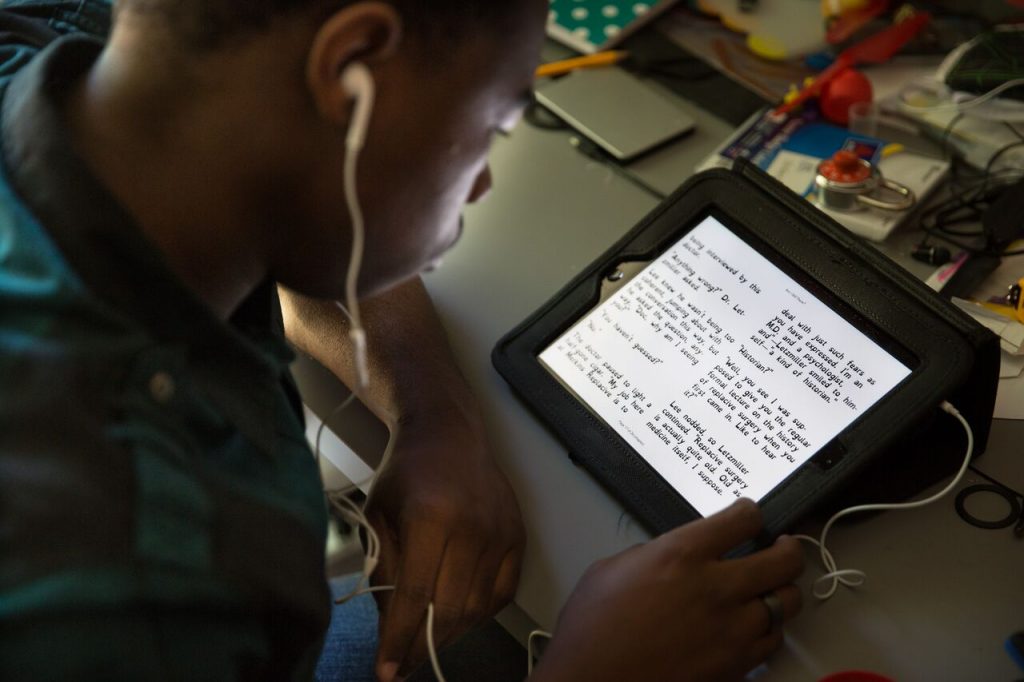

So what is the impact of these final orders on our library? Broadly, this injunction will result in a significant loss of access to valuable knowledge for the public. It means that people who are not part of an elite institution or who do not live near a well-funded public library will lose access to books they cannot read otherwise. It is a sad day for the Internet Archive, our patrons, and for all libraries.

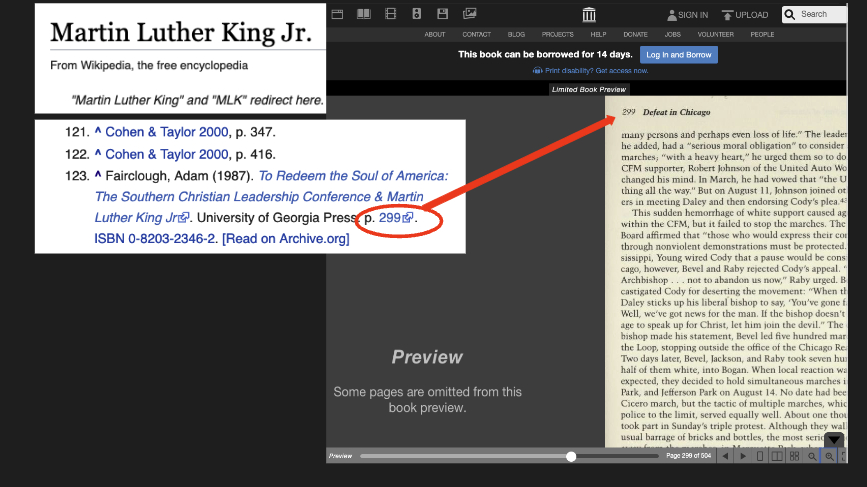

Because this case was limited to our book lending program, the injunction does not significantly impact our other library services. The Internet Archive may still digitize books for preservation purposes, and may still provide access to our digital collections in a number of ways, including through interlibrary loan and by making accessible formats available to people with qualified print disabilities. We may continue to display “short portions” of books as is consistent with fair use—for example, Wikipedia references (as shown in the image above). The injunction does not affect lending of out-of-print books. And of course, the Internet Archive will still make millions of public domain texts available to the public without restriction.

Regarding the monetary payment, we can say that “AAP’s significant attorney’s fees and costs incurred in the Action since 2020 have been substantially compensated by the Monetary Judgement Payment.”

Thanks to your continued support, our library is still strong, growing, and serving millions of patrons.

Libraries are going to have to fight to be able to buy, preserve, and lend digital books outside of the confines of temporary licensed access. We deeply appreciate your support as we continue this fight!