Guest post by Kay Savetz, professional web publisher and amateur Atari historian

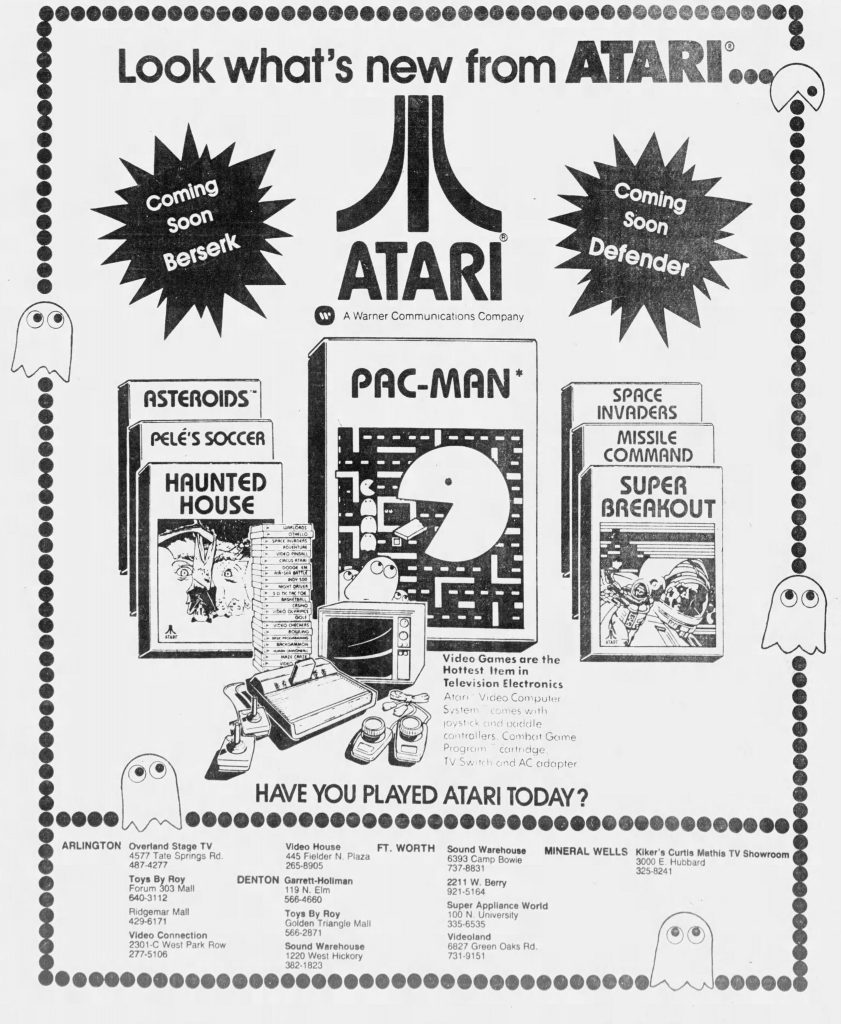

For years I hunted for the answer to the question: who wrote the adverting tagline “Have you played Atari today?” Atari started using it in print advertisements on April 1, 1982. Soon after, the words were sung in a jingle in many Atari TV commercials. As an Atari historian, the question plagued me: who wrote those words?

My computer historian colleagues didn’t know. I asked Nolan Bushnell, founder of Atari. He thought it might have come from their ad agency at the time, Doyle Dane Bernbach. But when both a colleague and I separately reached out to DDB, we hit dead ends. I searched Internet Archive, commercial newspaper archives, and library collections, all in vain.

In 2021 I created a script called TIARA — The Internet Archive Research Assistant — which searches Internet Archive every day for newly uploaded items that match my selected words and phrases. (You can get the script free from https://github.com/savetz/tiara). It diligently searched for “Have you played Atari today?” daily, with no hint to the answer to my question.

Until June 2022 — when there was a hit. A book called “Graphis New Talent Annual 2016” had been scanned just the day before by Internet Archive’s scanning center in the Philippines. The book was available for immediate online borrowing. I checked it out for an hour, and had the answer I needed in just a minute. There on page 7 is a bio for Robert Wain Mackall, which says that he wrote the “Have you played Atari today?” tagline while working at Doyle Dane Bernbach.

Finally, there was my answer! Internet Archive’s relentless scanning of books, its lending library, its full-text search capability, and my little TIARA script delivered a fact that I had been seeking for years.

—Kay Savetz

What are some things you’re exploring on the Internet Archive? Tell us in the comments!