Patrons come to the Internet Archive’s software collections for many reasons, and among the major reasons are some manner of playing historical software in our in-browser emulation environment. Well over a decade old now, the Emularity gives near-instant access to functional versions of what would otherwise be dormant software packages. If a patron wants to go from idly thinking they’d like to try something to playing a 2011 Pac-Man clone running in an obscure DOS graphics resolution, they can be experiencing it in anywhere from seconds to under a minute.

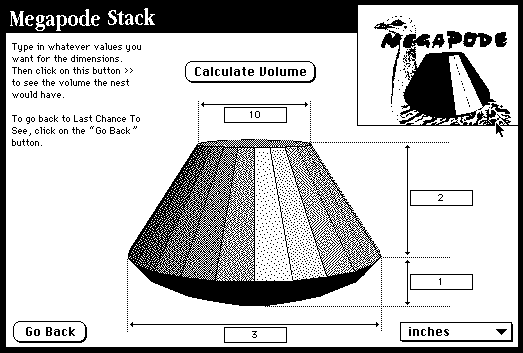

Naturally, “near-instant” is a nebulous, and inaccurate, portrayal of the time required to spin up the Emularity’s environment – a Webassembly runtime with an emulator embedded in it will come through, followed by whatever the total time to download the software itself afterwards. This playable version of Apple Macintosh System 7.0.1 requires 10 additional megabytes to download the hard drive image it is booting. That data will either snap down instantly on your fast connection, or be achingly slow on a less robust one.

Cooked into everything digital and online this present day is the fact that speed and efficiency win out over authenticity and reality. We go from thinking we’d like to hear a piece of music to hearing it (or never hearing it, as we can’t find it), in brisk flashes, a few clicks and a momentary pause. But listen to a track of music written decades ago, and a mass of assumptions by the creators of how you would experience these works no longer apply.

We’re not indicating the only way to enjoy Dark Side of the Moon is to see it mentioned in a magazine or fanzine in 1973, wander down to your local record store, see them stacked up near the front of a rack, and then buy one and take it home, gently unpacking the stickers and poster while playing the album in headphones or on speakers, cross-legged on your shag carpet.

…but they probably thought you were going to at the time.

Such it is, in the emulated world of software, that the way these works will be primarily enjoyed through all of time to come is as discrete blocks, loaded into a waiting process or slot, and then turned on moments after being selected. This is right and good – it’s a decent argument that many people would not want to sit through the “realistic” amount of time it would have taken to boot up software at the time of its release.

But maybe some of you do.

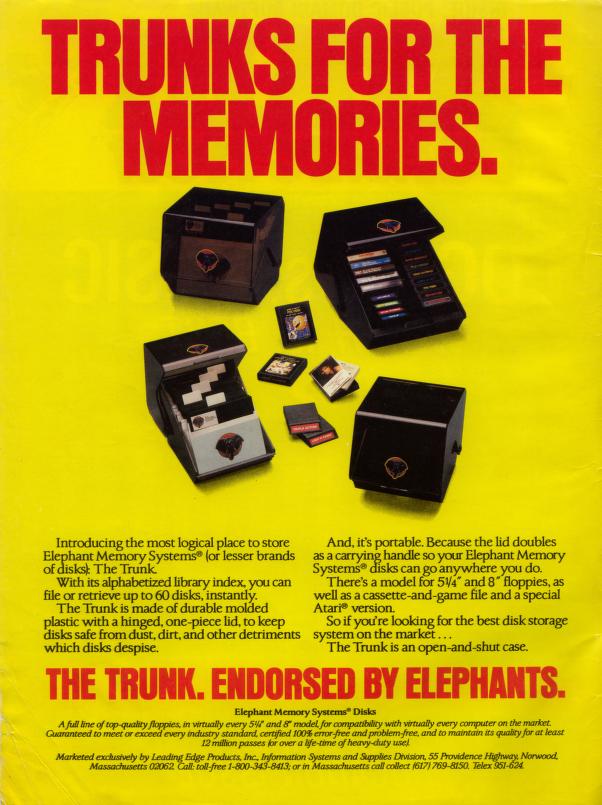

Most people who use computers know that they once loaded from floppy disks, plastic cartridges with magnetic plastic rings inside that could hold some small amount of data. Slow, weird, but the aesthetic experience of the floppy disk has, to some small amount, bubbled up into the present day. It’s seen as a “save icon”, or a reference to times long past, and there’s even a notable amount of “old floppy disks” found in family storage, where younger generations find them in the same way you might find an old smoking pipe or a saved wedding invitation.

But nestled in a relatively short span of time is the era of cassette-based loading, where actual audio tapes could have data stored on them, and played back to load into computers.

In terms of adoption, the cassette-based software period is marked by people entering it and almost immediately clawing their way out of it as soon as they can afford to. The combination of time consuming playback, limited data storage, and lack of read-write ease ensured that as soon as anything better came along, a user would leap to it.

As a result, it has become the case that not only are there people who consider themselves computer enthusiasts who have only a light glancing memory or awareness of cassette-based software – there are people who are not aware this ever even happened.

So, let us begin.

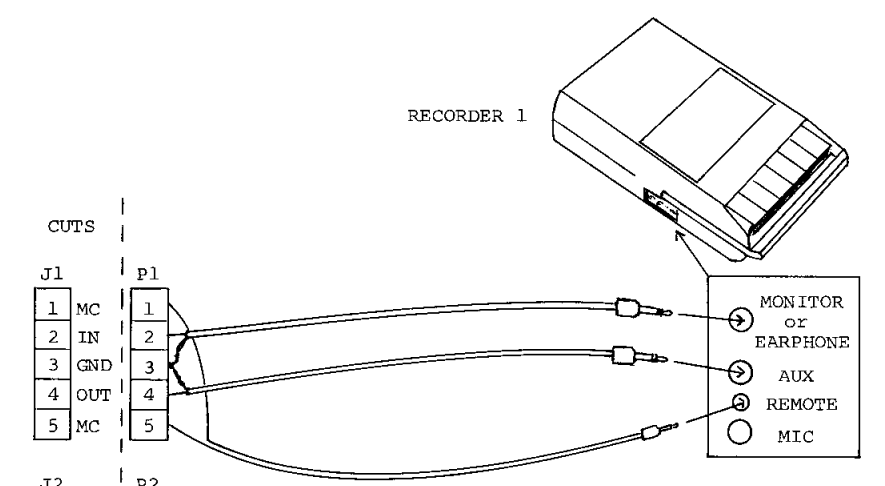

In the wild and wooly days of kit computers, where one of the major options was to be sent a pile of parts and instructions to screw, solder and assemble them into a functioning beast, the option of saving your code into a cassette tape machine was one of the possible storage options. And by “cassette tape machine”, we’re bringing back a dozen memories of schoolchildren in the 1970s:

And this is exactly what it sounds like, using the headphone and microphone jack of these machines that would normally provide language education and field recordings, and attaching them to circuit boards either recording to or listening to standard audio cassettes.

So, an expensive ($27.99 is $151 in today’s dollars.) machine to hook up but due to the dropping costs of blank cassettes, themselves manufactured in the millions to satisfy a range of customers, you could now tinker and toy on these computer kits and save out your digital creations to a medium with a fairly high chance of recovering them again.

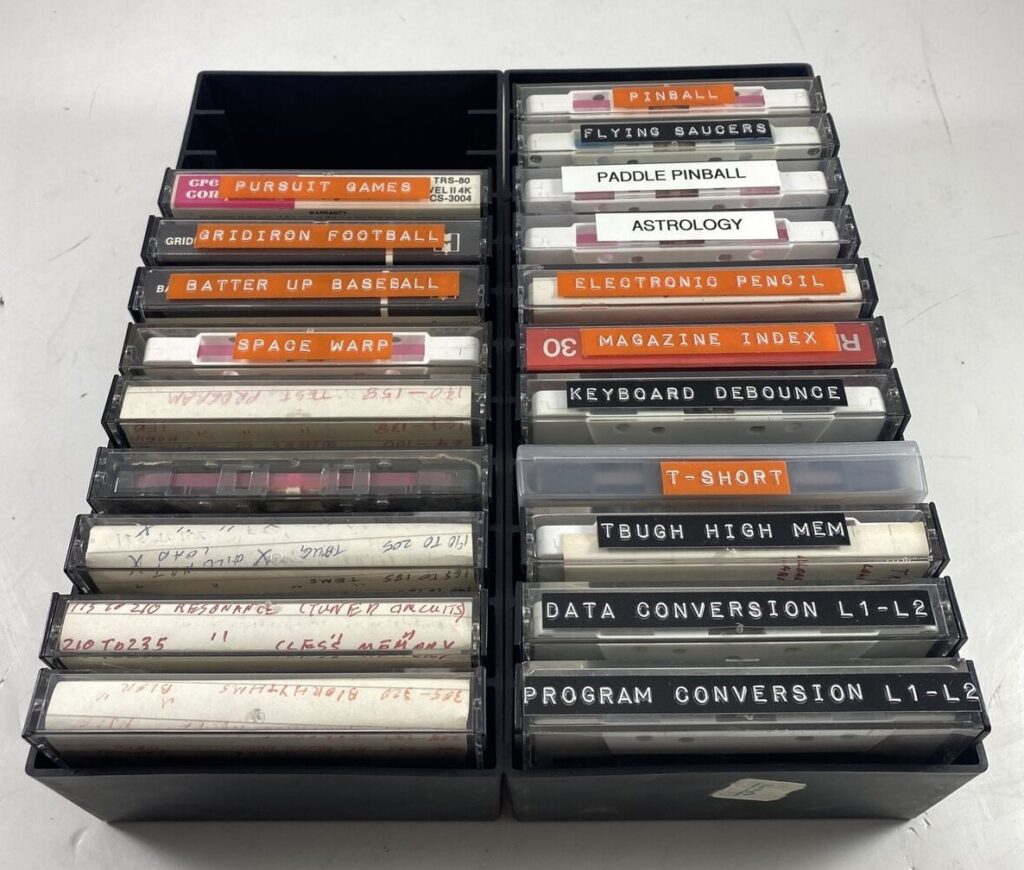

Combine the simplicity of the programs involved, the often-cheap tape medium being bought, and the use of labelmakers to create adhesive labels to describe the inside program, and you get a very memorable, very evocative 1970s-1980s aesthetic that will either confuse the new or warm the heart of the old:

As a side note on our introductory tour, it would be possible to save multiple programs on these tapes, but you had to be very careful about where on the tape counter each program was placed, so your works didn’t override each other, an art far above the head of the impatient or unwilling to rewind to the beginning of the tape and carefully watch a rising counter number to find fresh fields of data.

And the result, not obvious otherwise, are these glyphs providing you a possibly cryptic map of “dumps” (writing of the programs into the tape, following the counter as you would go). Note how in the label, a failed/broken program has to be left where it is on the tape; a combination of hearing the old program under an overwritten one, as well as not being able to predict how many feet down the tape a new program will take, means the road to data dumps is littered with broken memories.

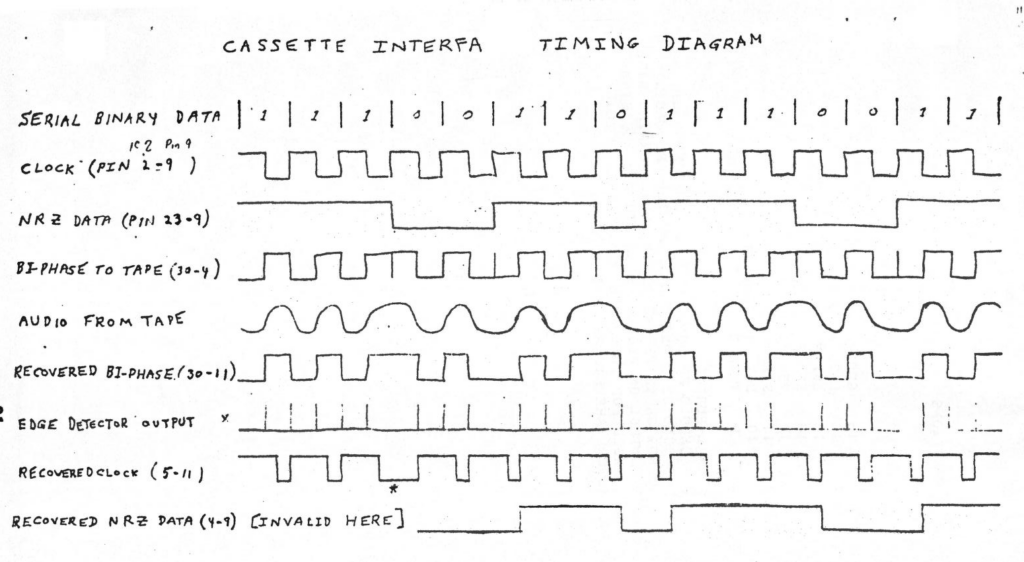

But what is exactly ending up on these audio cassettes (now considered to be data cassettes, or datasettes)?

Particularly curious folks can read up about examples like the Tarbell Cassette Interface and Protocols here in the bitsavers collection. But in more general terms, a variety of standards (and not-so-standards) had emerged where pulses of sound went onto an audio cassette, and these sounds reflected individual data that could then be interpreted coming back off the tape. The distinction is important here – these were not digital signals, but digital information encoded as analog/audio recordings. Think of someone shouting the word “42!” instead of digitally encoding up-down on-off data like “101010”.

The questions that might come to mind are probably myriad.

This sounds like it’s incredibly slow. Why yes indeed. The tarbell format/interface linked above brought in data at a screaming 187 bytes per second, that is, a couple short sentences worth of words. Compare that with a capability of 200,000 bytes per second of an early floppy drive and you can see why people would jump. (Naturally, modifications to the Tarbell format and alternative cassette tape electronics could increase the transfer rate to 540 bytes per second and above, but you’re adding complications.)

What even is a “Tarbell”? Oh, you mean Mr. Don Tarbell, creator of the interface in question, who wrote an extensive article about his work in Kilobaud magazine. (RIP to Mr. Tarbell, who died in 1998.)

Won’t it take a very long time to dump and read this data, at such a slow speed? Why, yes! That is the crux of this already-long article, coming up.

Is this the only way people ended up saving and loading data to cassette tapes? Why, no!

In the late 1970s-early 1980s, a myriad of cassette-tape based storage systems started being sold as an option for the “home computer” market, the plastic-wrapped, cheaper but all-in-one-already-built computers being sold by various companies in a bid to become dominant in the market. (Even the ultimately-winning IBM PC had a cassette port, although the system was generally sold with a floppy drive and it’s unlikely any significant number of people used it.) Each of these systems had slightly different approaches to how they wrote data on tape, and read it back, with speed differing notably between them.

By the late 1980s, it was rapidly becoming unusual to depend on data tapes to read and load to home computers, and the jump to floppies and ultimately hard drives and CD-ROMs came with mass adoption in the 1990s.

But it wasn’t completely gone, either.

In this zone, this Venn Diagram of a market of computer end-users with this exhausting set of possible media input devices, commercial creators had a heck of time. Intent on reaching every market they reasonably could, multiple formats meant multiple releases of the same programs.

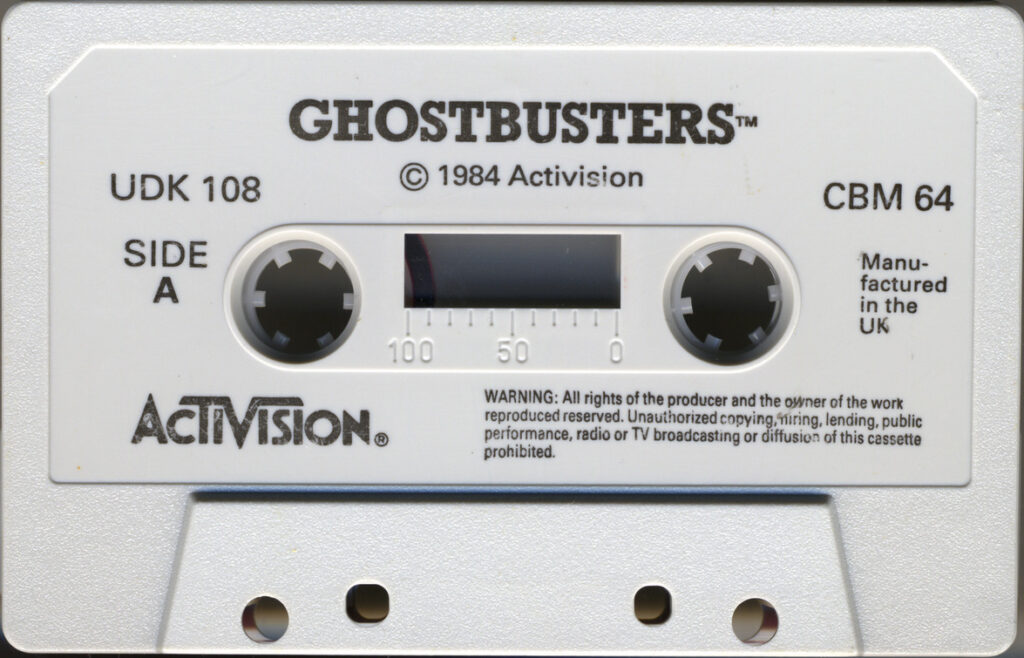

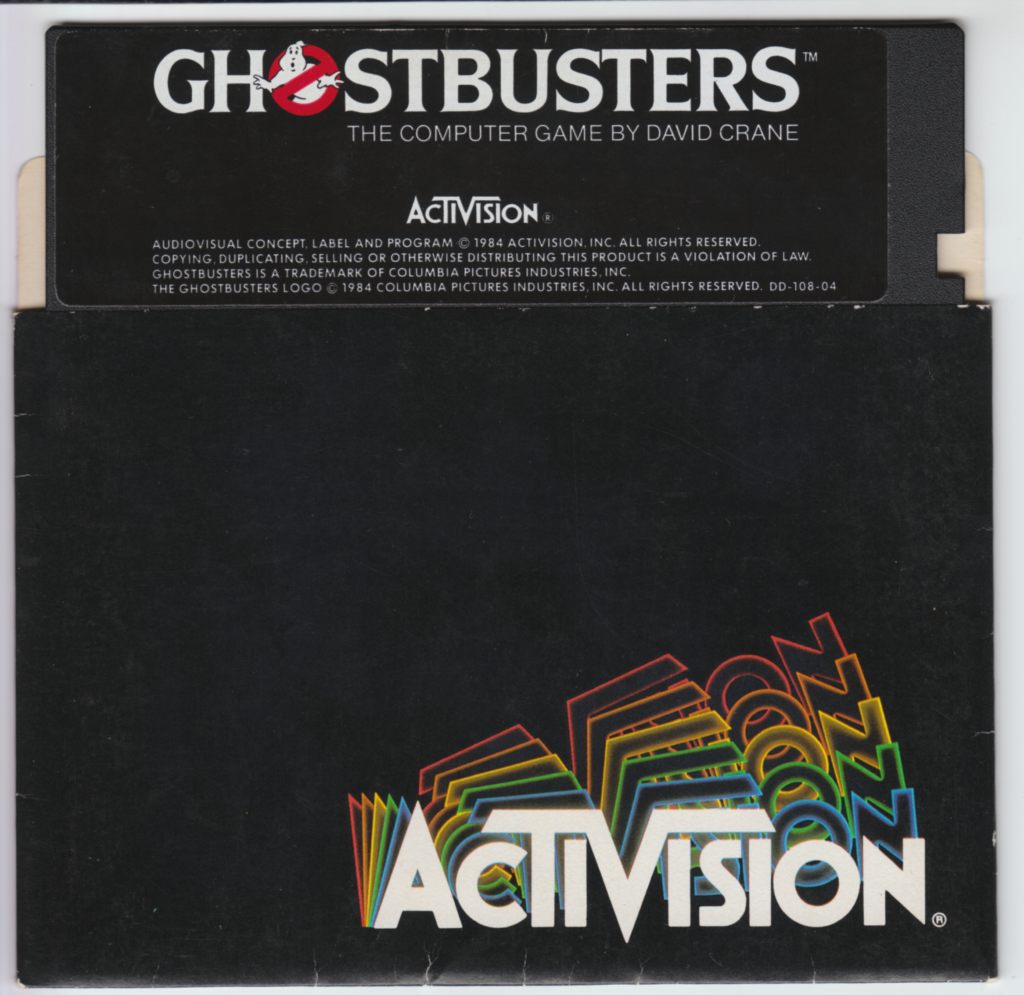

Does this mean that Activision had to spend the money to make a floppy disk version and a computer cassette version of the game Ghostbusters for Commodore 64? Yes, in fact they did. (One distributor, HES, even made a cartridge version, which was an Australia-only hack that put the contents onto a cartridge and forced a loading as if it was a floppy.)

For someone playing these games, the choice (or lack of choice) of medium meant their memories, experiences and consideration of the programs was very different, reflections of what configuration they could afford.

All these moments of time, washed away like spools of tape.

…unless you seek them out.

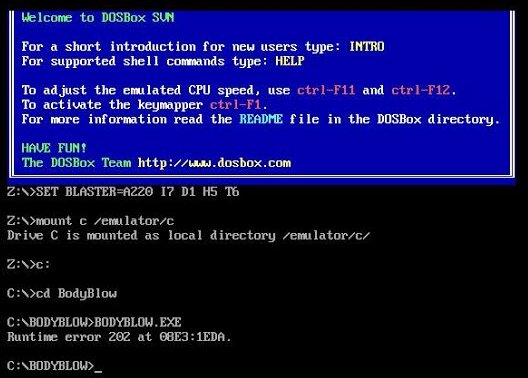

Emulation at the Internet Archive is designed to be fast, easy, and a snap between first thought and trying the software out. In general, this is the case; you decide you want to play a game and a very short time later, you’re playing that game.

This is an absolute gift, if your intention is to browse a lot of obscure, weird, or possibly-bad games, giving them minimal amounts of time while discovering what you were looking for. With a few clicks, you run down the massive lists of potential stops, watch the program come up, and give it a quick regard as to whether it’s worth your time or what you were seeking. As a finding and exploratory environment, it’s the way to go.

This comes at a cost, one which a lot of media/content is experiencing, now – your personal investment (time, patience, effort) is miniscule, meaning you will probably switch away in milliseconds if anything is annoying or non-intuitive. Annoying sound? Hard-to-figure-out key mappings? Slow title screen? Onto the next thing.

Loading cassette tapes of data is slow, slower than a modern person might consider reasonable. By using a variety of tricks, providers of older data tried to mitigate this by converting tape data, which would be a slow drip of data, into a single finished, packed set of instructions. The Z80 format, for example, is the result of a snapshot of the memory banks of a Sinclair computer, so if you visit the stacks of Sinclair ZX programs, you’re not loading in data the “old” way – you’re spinning up an already-loaded machine that is just starting off from the moment it all finally loaded in. Dropped off at the finish line, it still feels reduced in speed from today, but that’s just the (intended) experience of the machine it is running on.

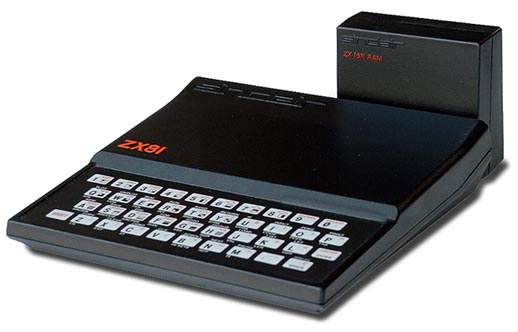

Two platforms at the Internet Archive currently provide the experience of loading programs from cassette tapes: The Sinclair ZX-81 and the Commodore 64. Both of these home computers flourished in the early 1980s, with use of them continuing longer based on the available hardware to users up until the 1990s. The ZX-81 itself faded before the C64, and the C64 saw transition to a (slow-reading) floppy drive that made cassettes fall out of favor as the decade moved on.

In both cases, there is the original data provided in a straightforward file; for the ZX-81 a .p or a .tzx tape data compilation, very small and compact. For the Commodore 64 cassette version, a .tap file with the information less compact, because the programs on the Commodore 64 could be significantly bigger.

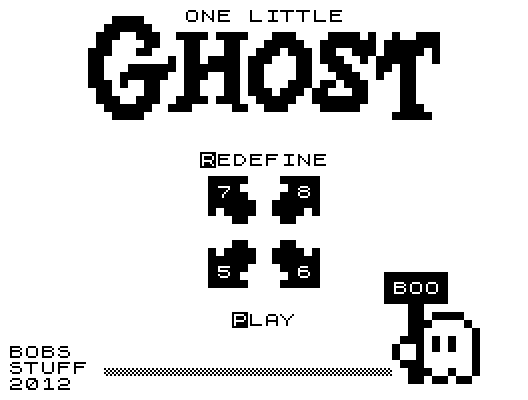

To this extent, loading a program on the ZX-81 emulation can be demonstrated on the program One Little Ghost, a 2012 retro-make version of Pac-Man that stuffs a whole lot of game into a very limited system. Going to this emulation and starting it, you are faced with not an instantly loading, black and white remake of Pac-Man, but this:

Incomprehensible! Mysterious! Uninformative! Welcome to home computing in the 1980s!

This is the gap between today’s fast-food version of computer history, and trying to get things running in the original days of the hardware. We’re not even addressing the peculiar aspects of the ZX-81’s RAMpack, an externally attached device for increasing memory, that was legendary for just falling off while using the machine.

To make this interaction of software-emulated machine and actual machine at all clear, instructions were added to the items added to the Archive’s collection, including this intimidating set of movements and keypresses to be able to set a cassette loading:

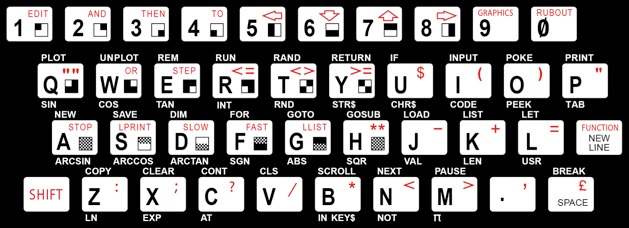

“Currently, emulation for this item does not auto-start. To load the ‘cassette’ this program is located on, press the following keys: j (which will appear as LOAD), shift-p shift -p (Which will appear as double quotes) and then ENTER/RETURN. Then press SCROLL LOCK on your keyboard, and the F2 key. If all is working properly, the system will bring up a box showing the cassette tape loading into memory. It will stop when complete and the emulation can be interacted with normally. Some games will run by themselves after cassette loading, while others can be started by pressing the r key and ENTER to run.”

As one last piece of intimidation, the instructions have to include a picture of what the ZX-81 keyboard even looked like:

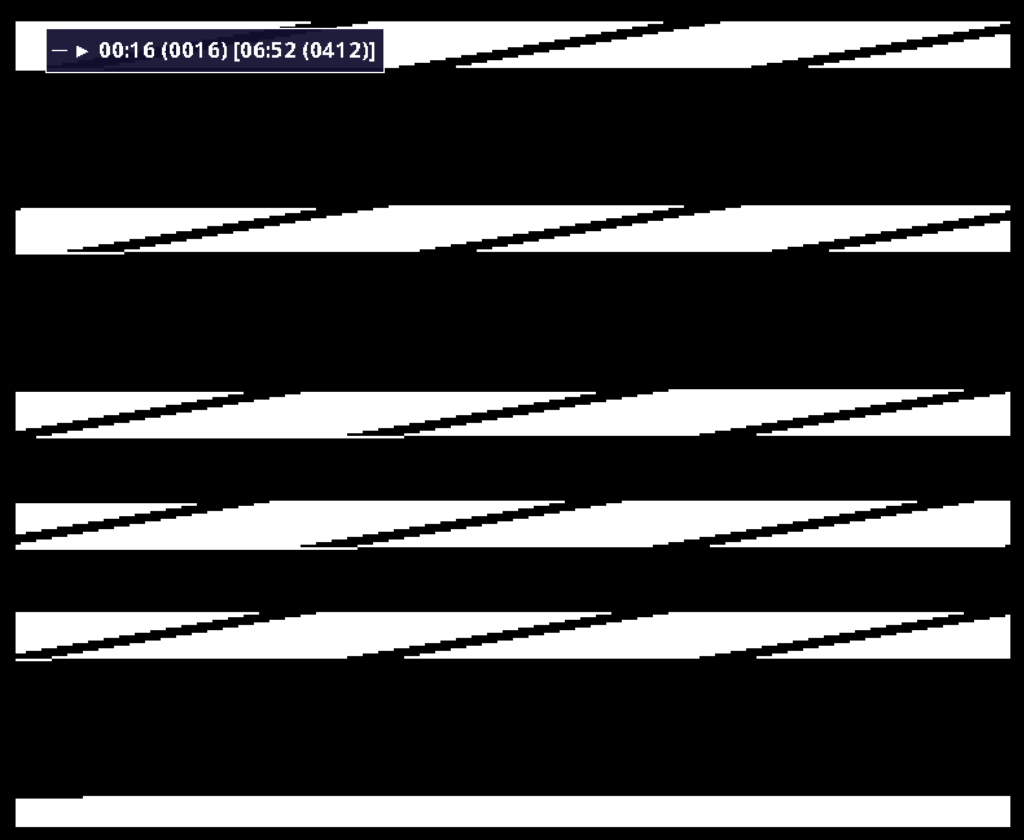

Once you negotiate the instructions, press all the requested commands, and sit back, the emulation rewards you with a screen not unlike this:

What is happening here is an honest-to-goodness cassette loading sequence. The constantly flashing graphics are an ancient hack to allow the end-user to know things are “working”, that the data is being successfully read off the tape. An additional convenience is provided by the emulator: on the top left is an overlay window indicating that it is 16 seconds into the loading of the data, and that there are six minutes and fifty-two seconds of loading to be done, for a total of 412 tape tick counts. Yes, you are reading that correctly: loading this program will take seven minutes of real time.

Perhaps it becomes obvious why so many shortcuts begin to arrive in emulation and why so many people were willing to spend the equivalent of a short vacation to bring their machines into the floppy age.

You can browse the ZX-81 collection of programs and see preview screenshots of the games. The good news is that a human didn’t generate them – a script called SCREENSHOTGUN started up, “pressed PLAY on the cassette player”, and then waited until the whole thing was loaded, and then removed most of the “loading” screenshots to bring you the result. That is a lot of saved misery.

Which brings us to the Commodore 64.

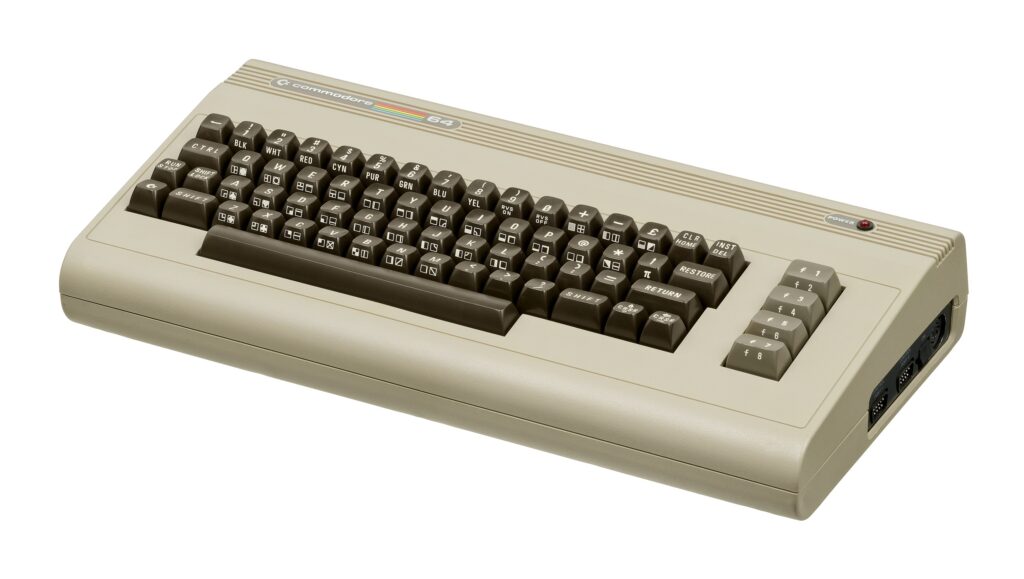

The Commodore 64 stands to live in fame forever as the most-sold, unchanged home computer in history. From 1982 to 1994, with no substantial changes in its configuration or capabilities, the C64 plowed on through multiple generations of industry standards, providing an inexpensive and dependable on-ramp for families and individuals to acquaint themselves with this “computer in the home” nonsense taking over the general populace.

While much can be made of its shortcomings, most of these have faded into a quaint memory of working around them. The breadth of software, the utter domination of understanding of the ins and outs of the machine’s quirks, and the toil of many millions of users means that the Commodore 64 is a giant in computer history.

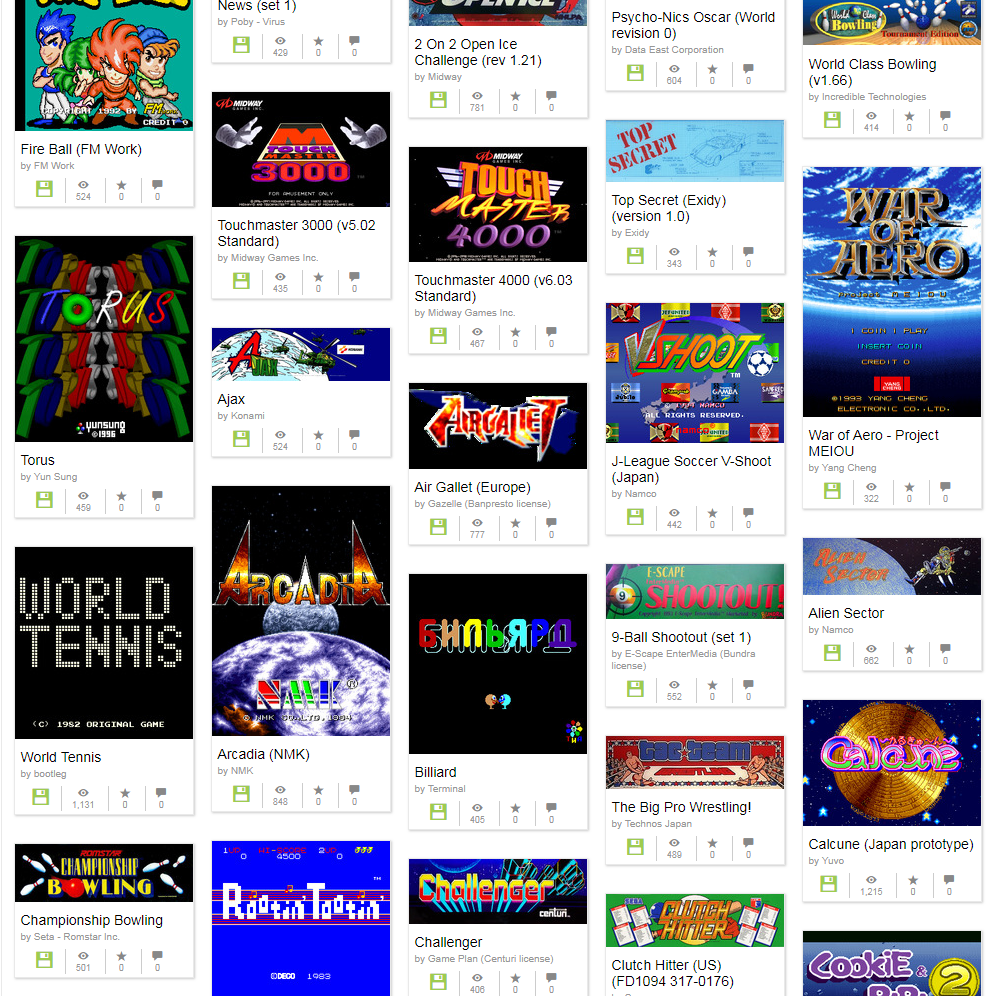

This long-lived history is reflected in the sheer mass of programs, games, applications and demonstration programs for the Commodore 64, numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

And to that end, a group has been working hard to preserve that most odd, increasingly rare-to-find subset of C64 works: the cassette-based commercial products that flourished in the beginning of its life.

And here we find ourselves, a significant number of paragraphs later, to what inspired this walk down tape-loading memory lane: the forgotten minutes-long time of the experience of loading these tapes on the Commodore 64, and the many different ways that companies tried to keep buyers from restlessly complaining the tapes weren’t “working” and giving up before the long loading times revealed the programs.

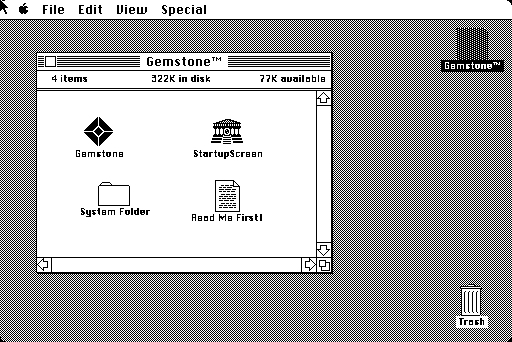

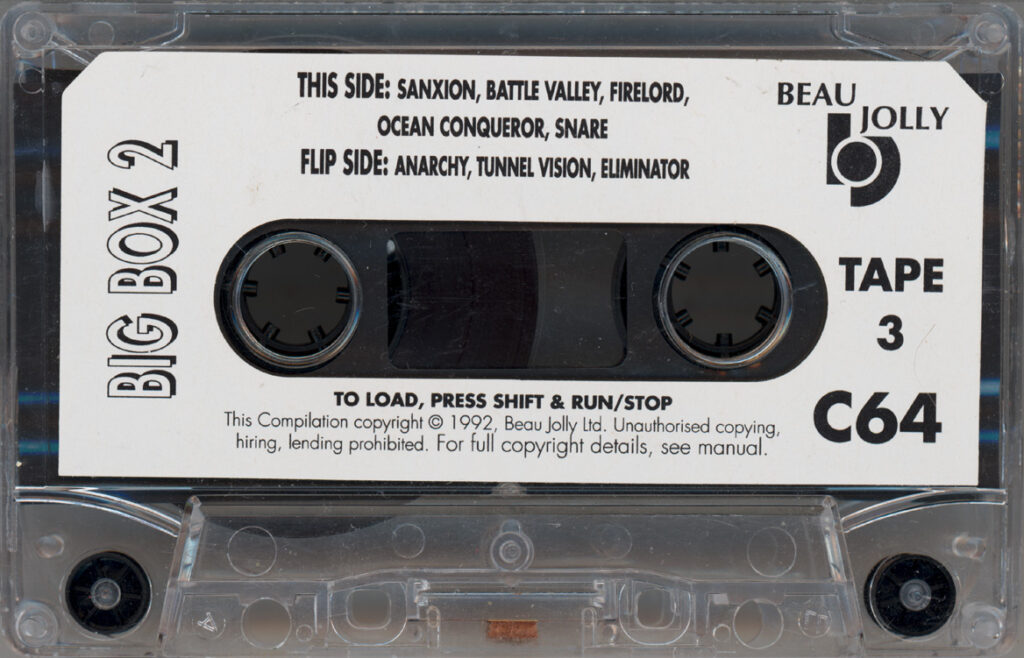

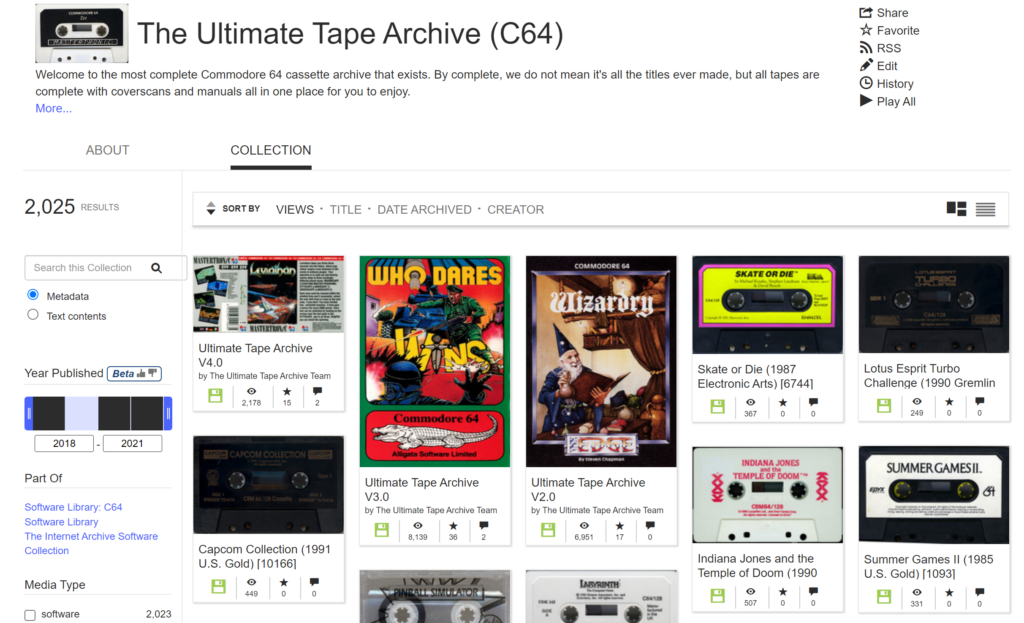

The Ultimate Tape Archive is an effort to preserve these cassette-based titles, including the data on the tape, scans of the tapes themselves, and of the cassette case inserts, papers inside the case, that provided instructions or cover art. The group behind this project have been tirelessly approaching the acquisition and preservation for years, and as of this writing, version 4.0 contains over 2,000 individual tapes.

To honor their work and provide the final step in experiencing them, it is possible to visit the Ultimate Tape Archive on the Internet Archive and emulate these items in the browser. Doing so, however, will be committing the slow burn, the steady and time-consuming cassette loading of the programs.

Luckily, for this essay, a machine stepped forward to do the work.

Utilizing the SCREENSHOTGUN program, the thousands of cassettes from this collection were “inserted”, “loaded”, and “played”, over the course of a month, to allow a later quick assessment of the experience of loading them. The reasoning behind this was that companies employed not just clever, but inspiring ways to distract end-users.

What follows are some of the highlights.

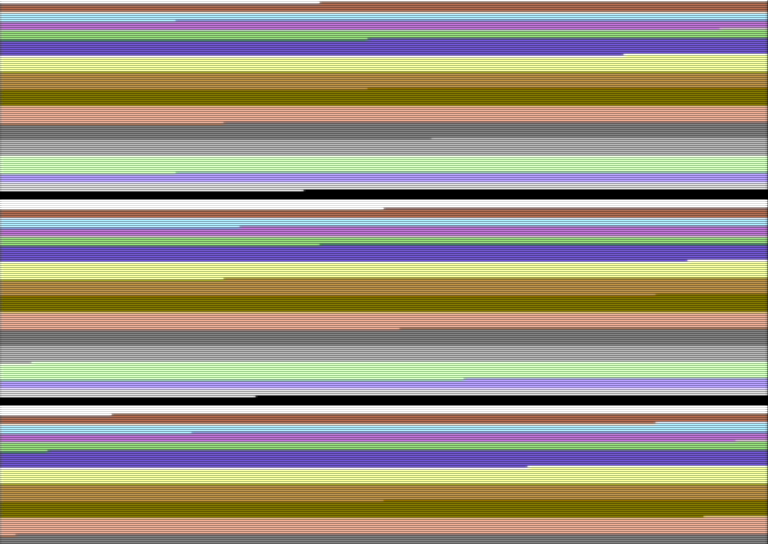

In most cases, the loaders will use the same trick we saw with the ZX-81, except with color: a rapidly pulsating, moving set of lines reflecting that something is happening, and data is coming in. A sense of “hold on, everything is working”, not requiring a lot of machine time to provide, and swapping between colors for a few minutes before a burst of music and graphics came at the end of a reward.

The main variations are the use of different lines or arrangement of lines to reflect this. For example, this thinner and more “high resolution”-feeling version:

This was more than sufficient for most cassette-based titles. But some wanted to go a little further to inform the user.

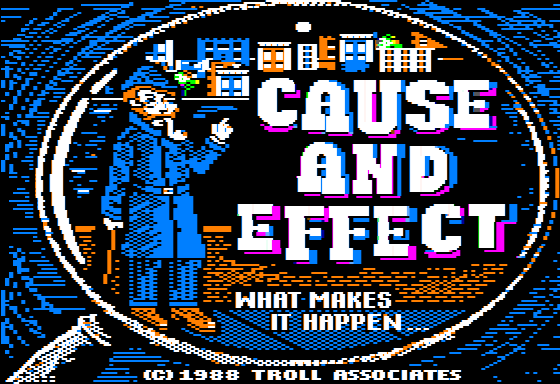

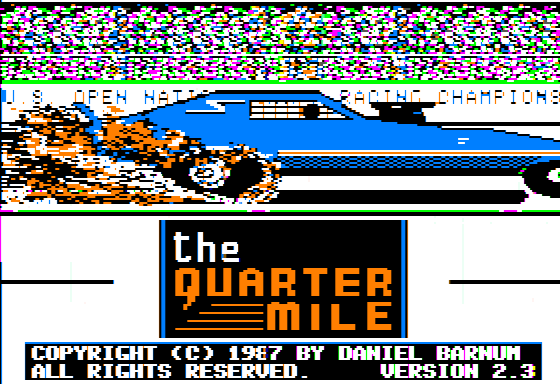

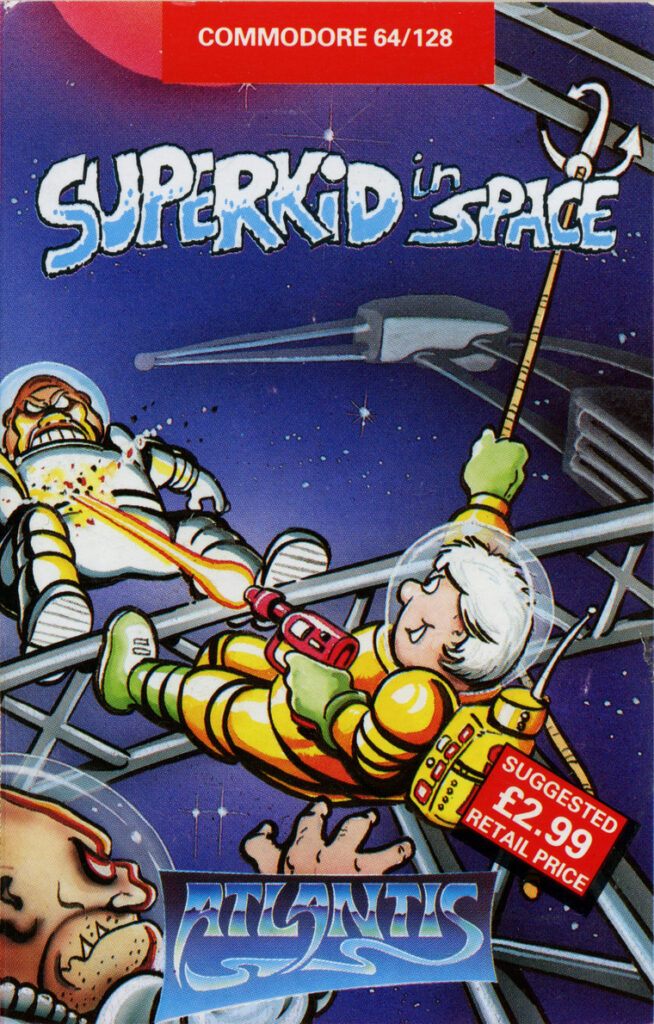

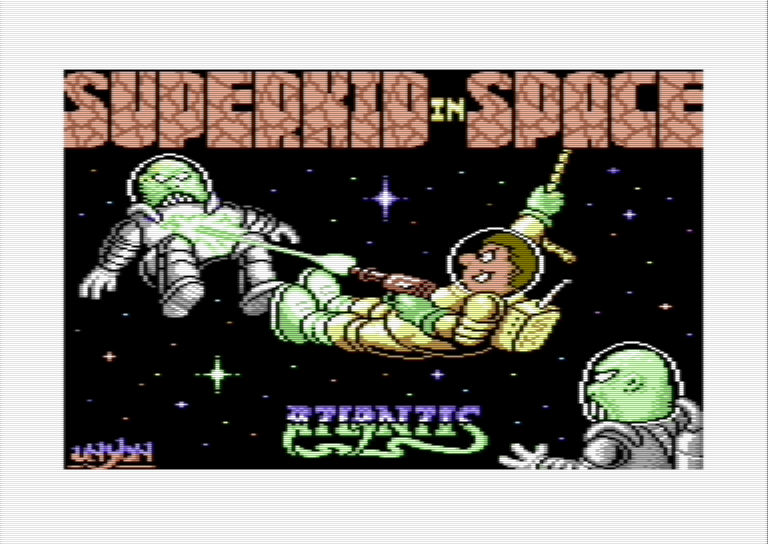

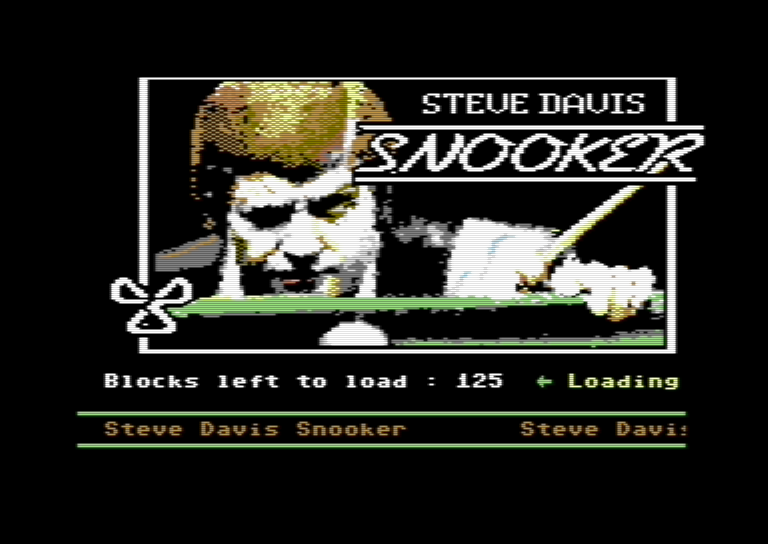

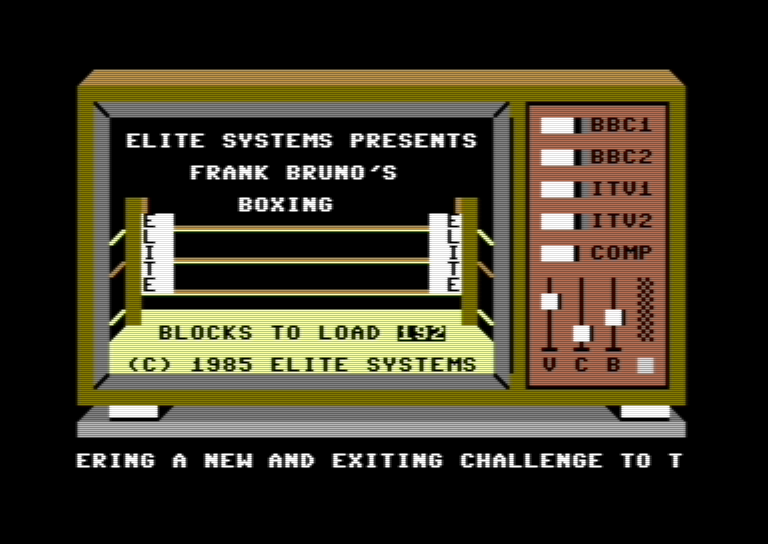

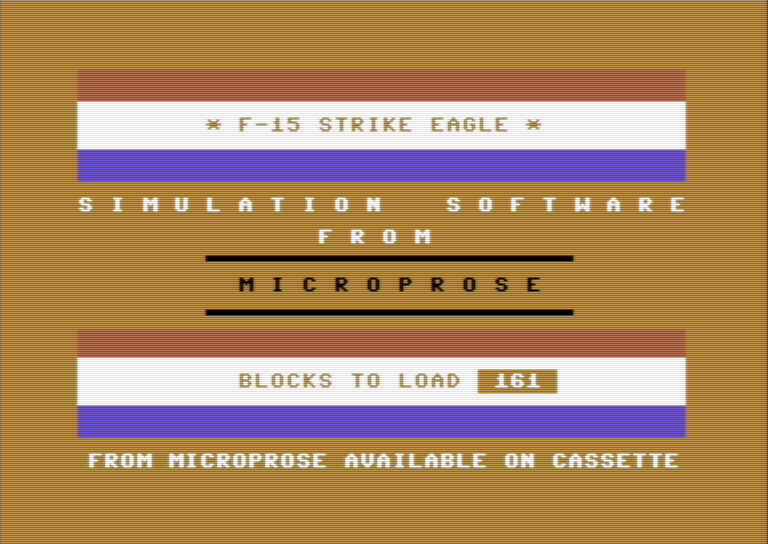

A significant upgrade was adding a sort of “loading screen” to the process, where the lines would still move, but around a “title card” that informed you what was “coming soon” to your computer. Some had nice graphics to accompany them, representing some attempt at recreating the printed artwork on the cassette insert.

An impressive upgrade, but not something to leave well enough alone to a generation of tinkerers.

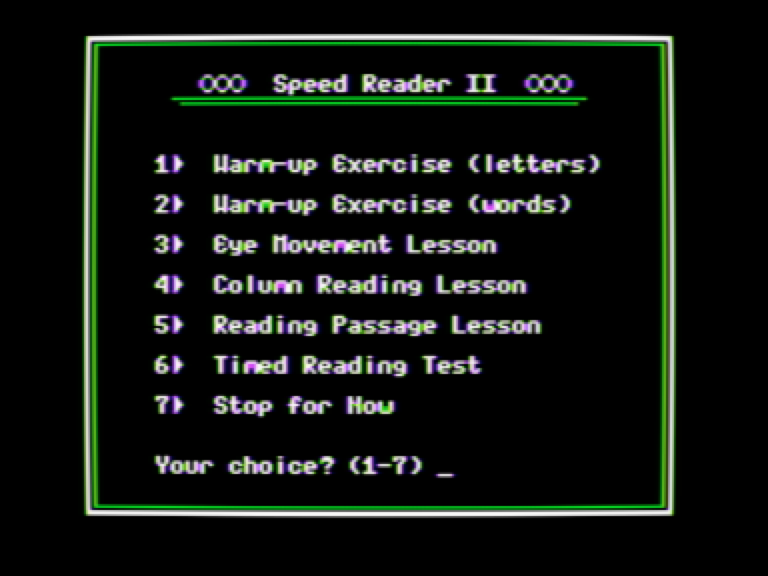

To give an answer of “are we there yet?”, some titles included calculated countdown timers to tell users how long they had to go before the game would go:

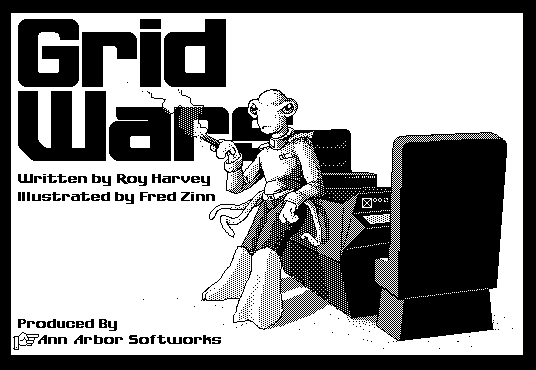

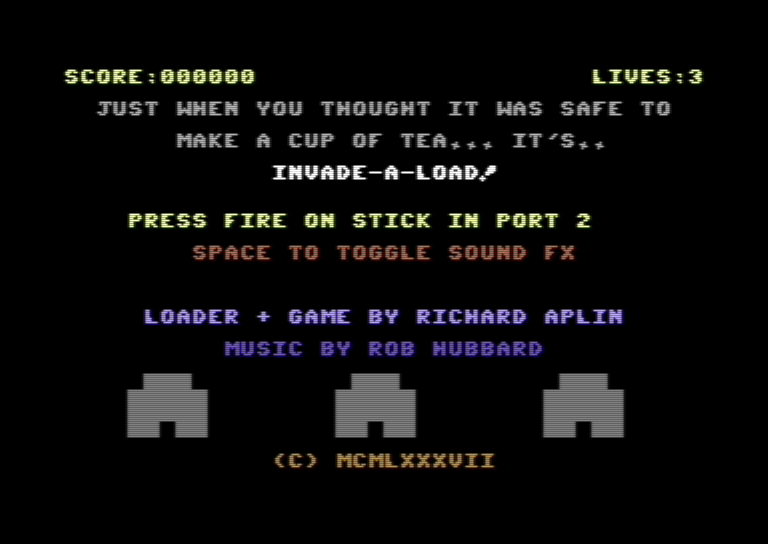

And again, this would have been a favorable solution to the “sit and wait” problem, but a handful of instances exist of the most rare of tape-loading systems: The Loading Games. Games that would be booted up by the system, that would then load the actual programs in the background while you played an amusement, either a song or a smaller game while waiting.

These are harder to discern using the screenshotting system, but a few are clear:

Perhaps not surprisingly, this clear and available innovation in software loading was ignored when Namco created a “play while you load” system in the 1990s, and they were granted a software patent that killed innovation in the bud for years. The epic story of the software patent for a game while waiting for a game to load was covered extensively by the Electronic Frontier Foundation upon its expiration in 2015.

We are, as a whole, incredibly lucky at how the state of in-browser emulation, built on open standards and persisting through most modern browsers, allows us easy insight into historical software and either experiencing or re-experiencing these bright lights of brilliant code. But we must also realize that a lot of what we are interacting with in the present day are, top to bottom, towering piles of shortcuts and “we’ll just skip ahead”, trying to accommodate a type of user that has no time or patience for how things were once. And this new type of user, ignoring or unaware of the lost minutes any choice could be, find it harder and harder to relate to what came before, the environment that those creations were made in.

Perhaps if you have a spare few minutes, a lull in your day, you might consider browsing the stacks of the Ultimate Tape Archive and finding a compelling cassette tape cover, look over the JPG scans of the cassette inlay and printed instructions, and “press play on tape”, feeling some moments of anticipation as another gifted person’s efforts provided you with a chance to experience a very complex joy emanating from a very simple machine.