Guest post by Dylan Gaffney, Information Services Associate for Local History & Special Collections, Forbes Library.

This post is part of a series written by members of the Community Webs program. Community Webs advances the capacity for community-focused memory organizations to build web and digital archives documenting local histories and underrepresented voices. For more information, visit communitywebs.archive-it.org.

Forbes Library has been a member of Community Webs since its inception in 2017. At that time, we were hopeful that the program would allow us to create an archive which more fully represented the community in which we live, and provide a more diverse history/record of our region and the people we serve. This project inspired archives staff to examine the many silences in our archives, and make plans for the ethical collection and preservation of materials that would help fill in these gaps in our historical record. At the same time, the library had begun to shift its focus toward collaboration with other local historical and community organizations.

In the years following the kickoff of the Community Webs Project, Forbes library co-hosted multiple series of exhibits, films, workshops, walking tours, and community reads on themes of mass incarceration, the Underground Railroad, and the history of slavery in our region. These events, and the passionate response of the community to them, inspired us to continue seeking out collaborations, large and small, and solidified our view that surfacing stories of people who had been underrepresented in the archives should be a core value in our work as an institution.

This work inspired Forbes Library, Historic Northampton, UMass Amherst, and the Pioneer Valley History Network to take lead roles in the 2021 Documenting Early Black Lives in the Connecticut River Valley project, which seeks to gather the fragmentary information about Black lives from the wide range of sources and archives in Western Massachusetts so that a whole might be perceived that is larger than the sum of those parts. The project, to date, has surfaced over 3500 records or references to people of color, enslaved and free, in Western Massachusetts from the 17th through 19th centuries. These histories are being made available through the project’s database and on the project website. We contributed an essay titled Searching for Black History in a Public Library Archive to the Project Handbook on the experiences and takeaways of doing this work from a public librarian’s perspective.

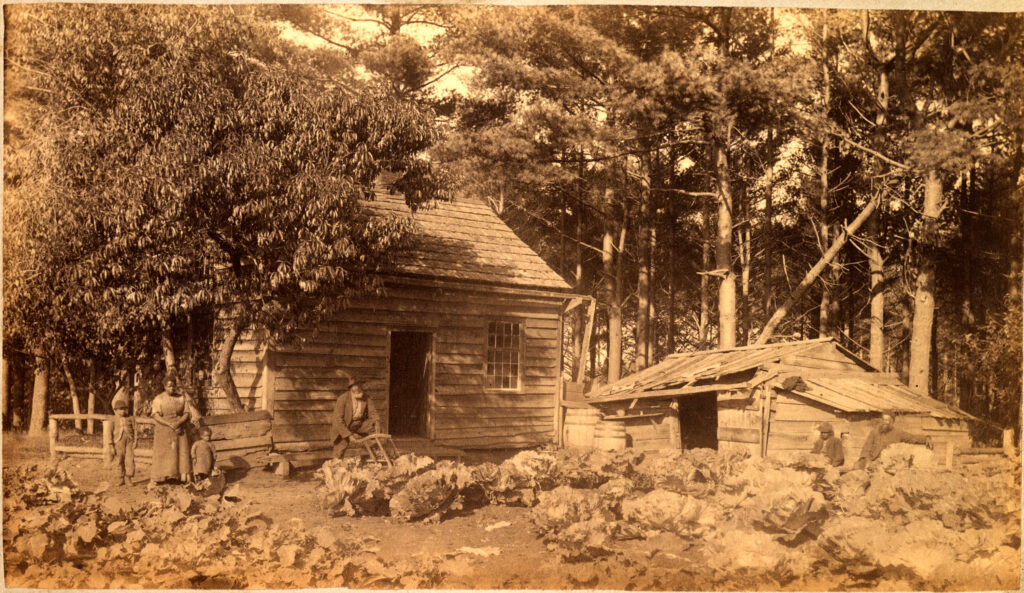

We know too little about Black lives in rural and small-town New England, and the places Black residents were able to carve out for themselves in these communities. With this project, we hoped to uncover names, details of their lives, and some small sense of how people of color survived in the Connecticut River Valley before and after the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts in 1783. At the kickoff event for the project, UMass Amherst professor Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina mentioned challenging the assumptions of others (sometimes called Gatekeepers) who “might be quick to discourage a researcher interested in Black History, reporting that they don’t have much…or not thinking about ways that records of white families might be useful to this research” Gerzina remarked that researchers, curators, and librarians should ”start from the perspective of presence.”

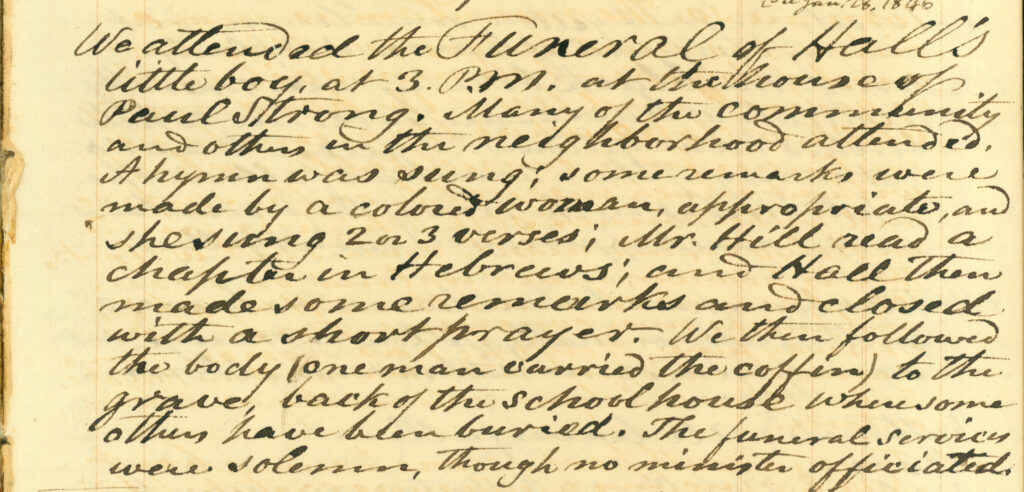

As the Documenting Black Lives project was undertaken with grant funding, and the time thus limited, we needed to develop an approach that would be productive right away. We identified several collections in the library’s Hampshire Room for Local History that we expected could be productive resources for identifying enslaved people in the area. The most promising of these was the Judd Manuscript Collection, a collection of 60+ volumes created by local newspaper editor and historian Sylvester Judd in the 1840s. The manuscript was originally purchased from the Judd estate by local historian James Trumbull and subsequently sold to the trustees of the library. It has been the property of the library since 1904, but use has been limited to a small group of academics and local historians who were aware of the contents and could physically visit during our few open archives hours. Those who knew of its tremendous historical value had discovered that it features content documenting Indigenous lives, enslaved people, and free Black people in New England and had used it to research Indigenous culture, the history of colonial settlement, enslavement, and the early abolitionist movement in the area.

Public Historian and Author Marla Miller on the value of Judd:

“Sylvester Judd, in his transcriptions of historic documents as well as the conversations he described with local residents, preserves extraordinary details that survive nowhere else. Because of Judd’s meticulous, wide-ranging work, I was able to gain insight into the lives of laboring people that would never otherwise have been possible…Judd’s notes preserve genealogical information about enslaved people that is found nowhere else. The Judd manuscript is almost archaeological in nature, with shards of evidence that can be unearthed via careful scrutiny. As he records, for instance, who had the first piano in town, who laid the first carpet, the sound of the geese squawking through Sunday sermons, and a hundred other small details of daily life, a picture emerges that simply cannot be found in any other kind of more formal or systematic archival material. These pages, filled from edge to edge with his notes, cross references, sketches, and other materials, simply teem with the kinds of details that historians crave, but cannot hope to find—except in Northampton.”

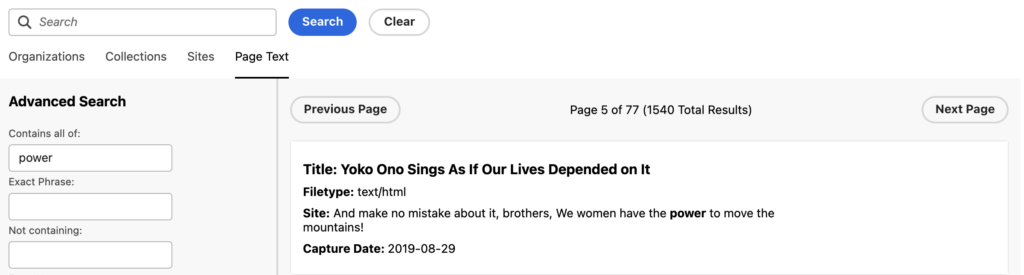

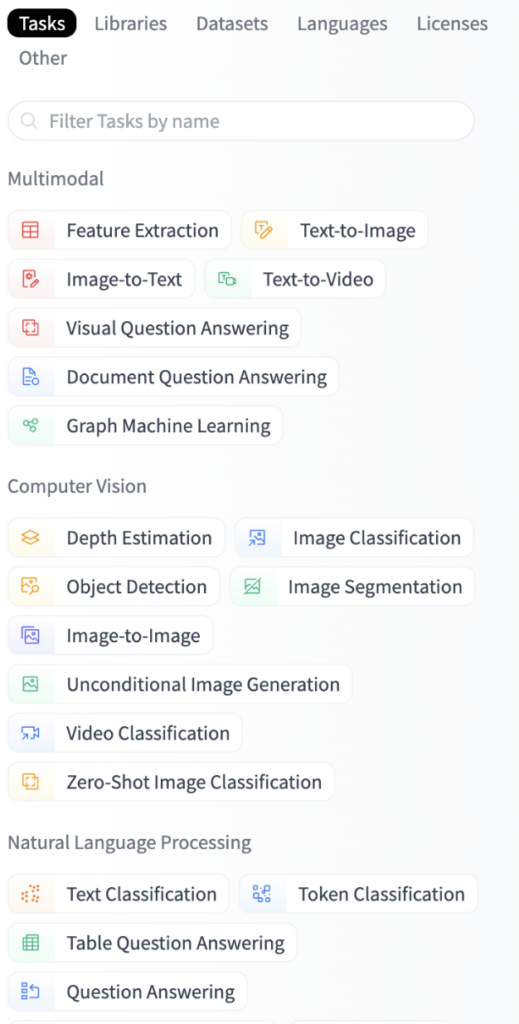

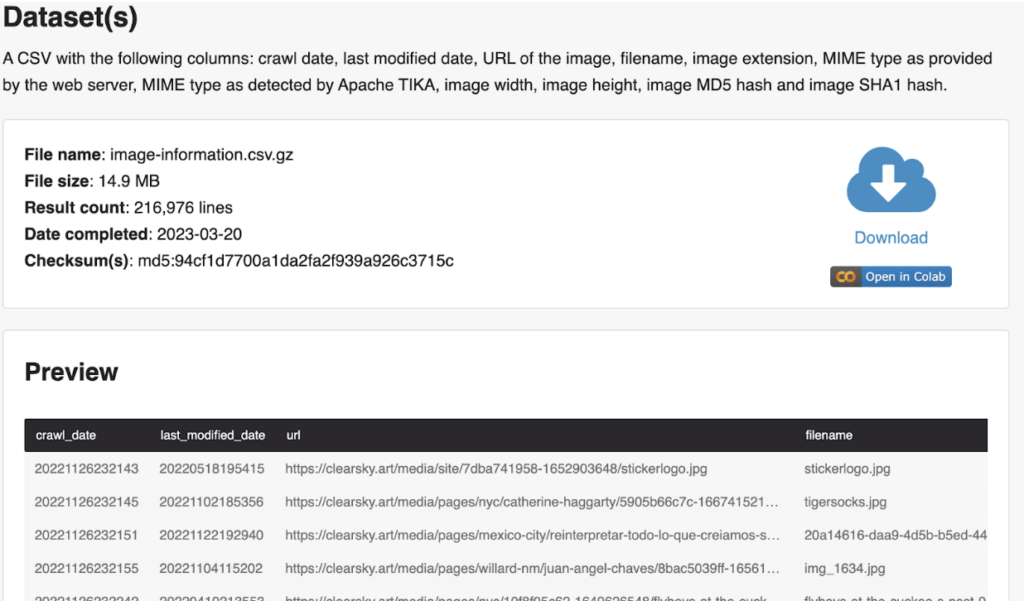

If we start from an assumption of presence (of underrepresented people both in the community and in the archives), the primary obstacles to discovering and surfacing information in collections like ours, often revolve around issues of access, and methodologies for search and discovery. We had long dreamed of digitizing all 60+ bound volumes of the collection to make them available to a wider group of researchers and the public at large. When the Community Webs program began to explore funding for a digitization program dedicated to expanding the amount and diversity of locally-focused community archives available online to users, the Judd Manuscript Collection seemed a good fit.

Now that the volumes have been digitized, our mission is to spread the word about their value and availability, so that the materials within can inform and inspire new research and discovery. As an illustration of the value of the collection and its contents, it is useful to look at how the increased availability of this resource could lead to new discoveries in long hidden collections. As an example, I will examine how Judd enriched our understanding of one local Black family.

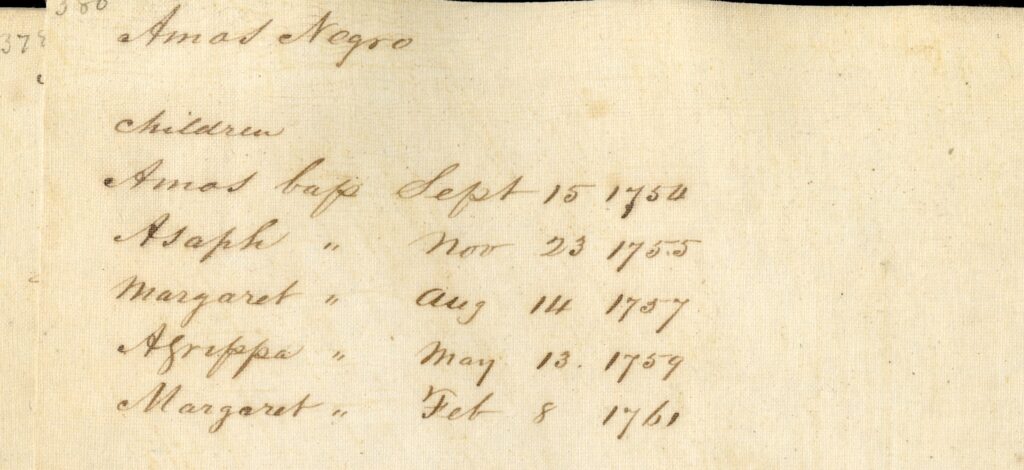

Judd entry for the Hull Family. Northampton Genealogies Volume 4, p. 380.

Judd devoted entire volumes to genealogies of local families, but the 600+ page volume on Northampton Genealogies contains, to our knowledge, only two Black families, both listed without last names. The work we had done in the Documenting Black Lives project enabled us to compile a list of 3500+ entries for Black residents of the region in the period between the 1650-1900. We recognized these names as those of Amos and Bathsheba Hull and their children. Bathsheba can be found elsewhere in our own archives as a member of the Church of Christ during Jonathan Edwards ministry between 1729-1750, in records recorded by Jonathan Edwards own hand.

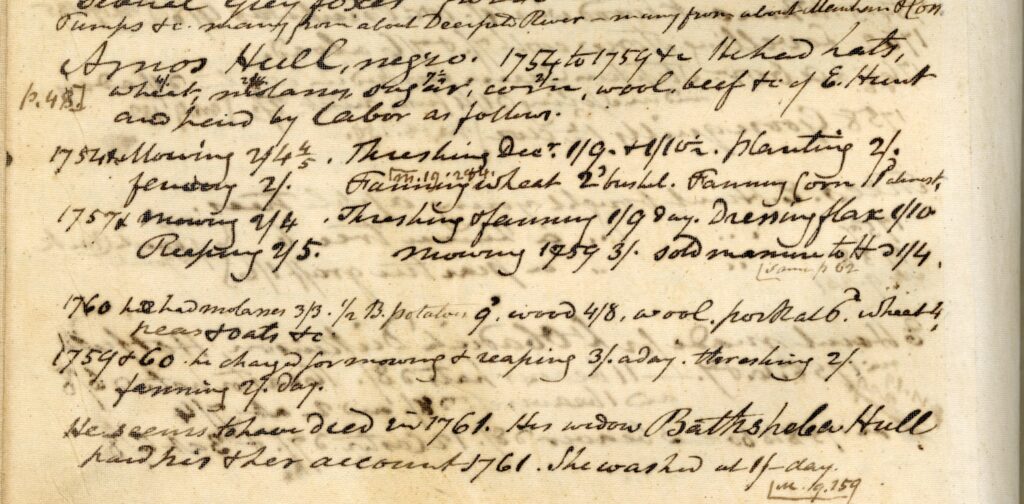

This entry transcribed from a local merchant’s account book shows items purchased by Amos Hull, the services he would perform in exchange for goods received, and the rate at which he was paid. It notes that in 1761, the same year their daughter Margaret was born, Amos Hull died. Afterward, his widow Bathsheba paid for his and her accounts by washing. Bathsheba surely would have a difficult time supporting multiple children without her husband, and documents subsequently found elsewhere in our archives and in other institutions prove this to be the case.

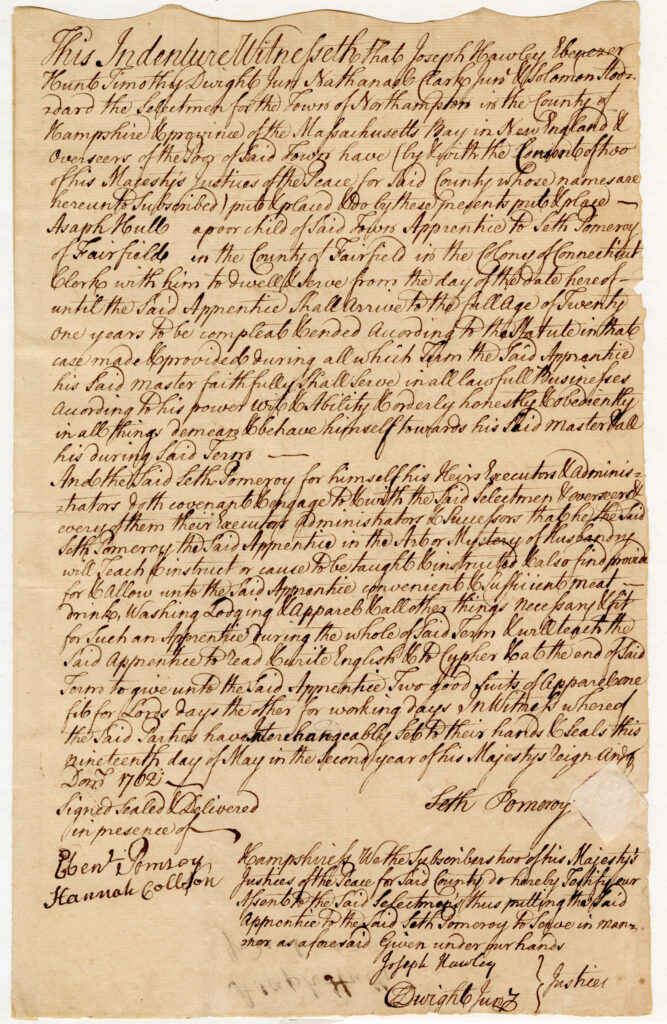

Asaph Hull’s 1762 Indenture Record. Northampton Manuscript Collection.

By 1762, a document found elsewhere in our archives records their son Asaph indentured to Seth Pomeroy, who is well known for his service in the French and Indian War and would go onto fight at the Battle of Bunker Hill and achieve the rank of Major General.

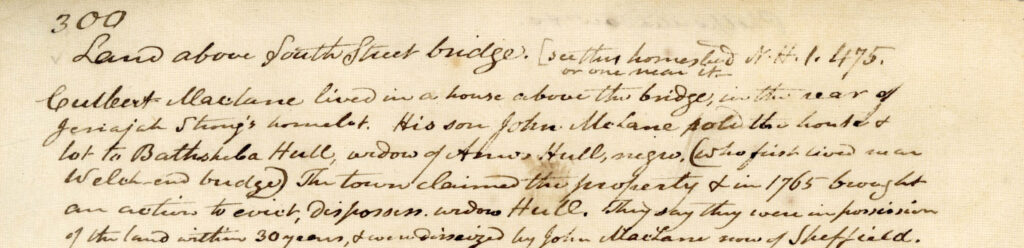

Judd entry describing the town seizing Bathsheba Hull’s land. Northampton Vol. 2, p. 300.

Bathsheba and her family come up again in several entries in Judd, including multiple mentions of the town seizing her land and displacing her from it in 1765. This cruel act forces Bathsheba and her young children from the town. Bathsheba and her son Agrippa would relocate to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. It is in Stockbridge where Agrippa Hull would enlist in May of 1777, and served for the remainder of the Revolutionary War in the Continental Army, including witnessing the surrender of British General John Burgoyne at Saratoga, New York, enduring the winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge and was part of the battle at Monmouth Courthouse, New Jersey in June 1778. He then served as a personal assistant for the famed Polish general, revolutionary and engineer Taddeusz Kosciuszko and became a close friend of the General, during their years of War Service together. Agrippa’s story and friendship with Kosciuszko, along with Kosciuszko’s friendship with Thomas Jefferson is examined in Gary Nash and Graham Hodge’s 2012 book “Friends of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson, Tadeusz Kosciuszko, and Agrippa Hull”.

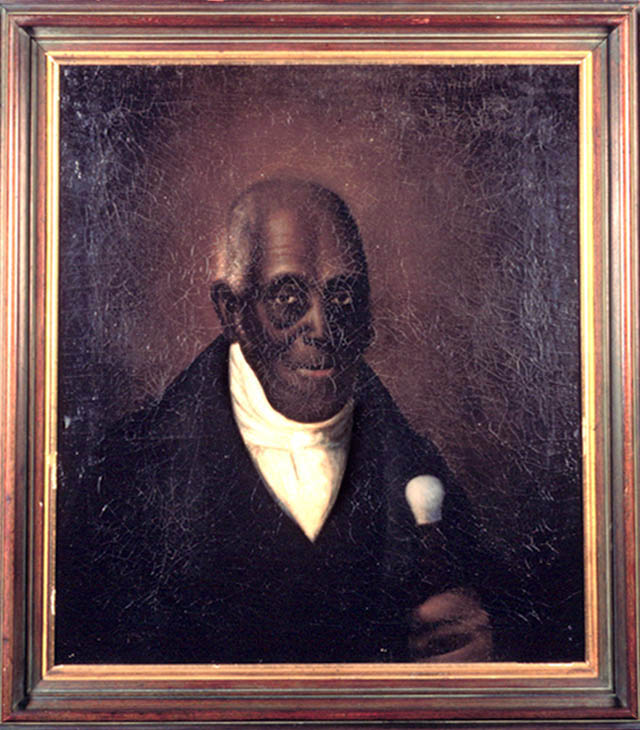

Portrait of Agrippa Hull, Courtesy of the Stockbridge Library, Museum & Archives.

Agrippa Hull went on to become the most prominent black landowner in Stockbridge MA and is buried along with his wife and children in Stockbridge Cemetery. His brother Amos Hull, Jr. also fought in the Continental Army, and surfaces in Belchertown MA records recorded as part of the Documenting Black Lives project.

This is just one brief example of the elaborate web of information that can be revealed when we prioritize the surfacing of stories that had previously been hidden in our collections, increase access through digitization, and collaborate to research and promote the information within.

As Marla Miller wrote in her letter of support for the NHPRC Archives Collaboratives grant:

“ We can hardly wait to learn— alongside the many other academic and avocational historians whose work will be enriched and transformed by these records—what else remains to be discovered. Once available in digital form, available for scouring by researchers with their own wide range of questions, these materials will certainly spark, inform, and enrich generations of new research, from student papers to dissertations to academic monographs. It is almost impossible to predict all the ways the volumes might reshape historiography, as well as conventional historical wisdom, because the contents at present are comparatively difficult to ferret out. But to be sure, these volumes have the potential to transform local and regional historical understanding, and once digitized, will certainly come to the attention of researchers nationwide.”

Click here to browse the Sylvester Judd Manuscript Collection on archive.org.

The Internet Archive and Community Webs are thankful for the support from the National Historical Publications & Records Commission for Collaborative Access to Diverse Public Library Local History Collections, which will digitize and provide access to a diverse range of local history archives that represent the experiences of immigrant, indigenous, and African American communities throughout the United States.