In early March 2020, much like the rest of the United States, the staff of the Internet Archive transitioned to fully remote work in anticipation of the prolonged pandemic. This change was monumental and, like all workplaces, we discovered the challenge of sustaining a feeling of connection, morale, and joy within the team.

Recognizing this challenge, our Director of Media & Access, Alexis Rossi, came up with a creative solution. It was already part of our workplace culture to have two weekly all-staff meetings—one at 10am PT Monday morning, and another at Friday lunch. As everyone moved to joining those meetings from home, Alexis began hosting short concerts before them by performers, particularly musicians, to uplift our team’s spirits. These concerts provided not only entertainment, but also a means of keeping our team engaged and the performers booked during uncertain times.

The initiative began with a performance by Alexis’s friend, Jefferson Bergey, whose talent for musical theater and captivating stage presence set the stage. At the time, we envisioned organizing these concerts for just a few months, as none of us could predict the duration of the pandemic.

Fast forward several years and our work world has undergone a profound transformation. Encouraged by the overwhelmingly positive response from our now mostly remote staff, we decided to continue the program, thus giving birth to “Essential Music Concerts From Home.” As we approach our fourth anniversary in April, we reflect on how this simple yet impactful idea has helped sustain our remote workplace culture through the years. We thought it would be fun to offer you a glimpse into some of the unique musical encounters enjoyed by the Internet Archive staff with some exceptionally talented musicians.

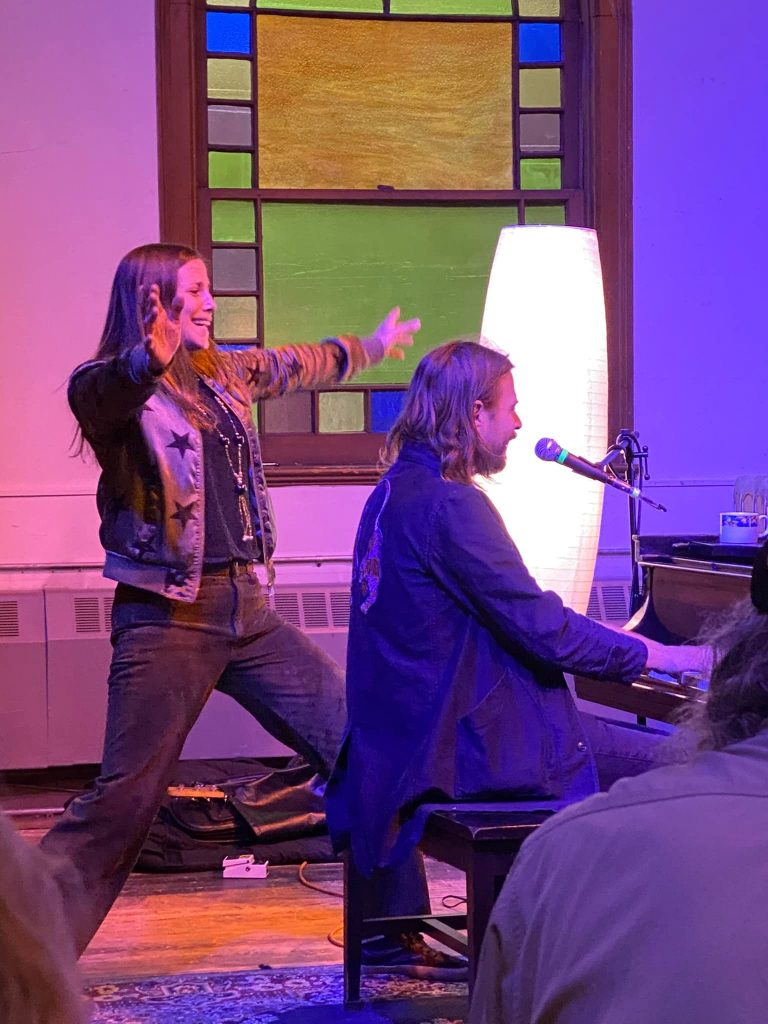

Jefferson Bergey

Jefferson Bergey is a professional musician and cherished figure in the Bay Area, known as “Fun for Hire.” His musical style epitomizes versatility, adapting to any desired vibe or genre with ease. Drawing from the rich foundations of jazz, blues, pop, folk, bluegrass, and rock, his songs are crafted with a distinct flair for musical theater. He is such a popular Bay Area performer, there’s even a burger named after him.

Jeanie & Chuck Poling

Jeanie & Chuck Poling have been making music together since 1982. Their act, Jeanie and Chuck’s Country Roundup, specializes in honky tonk and bluegrass tunes played on acoustic instruments. Their performances are known for blending music, humor, and showmanship to entertain audiences. Additionally, Chuck has served as the emcee at the Rooster Stage at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass since 2012.

Joliet

Joliet, hailing from Kansas City, is an independent singer/songwriter and live music streamer. Her vocal style is both distinctive and commanding. With her bold and expansive sound, Joliet offers up heartfelt and captivating charm. She plays live on platforms such as Smule and Twitch, where she has introduced her original compositions to audiences worldwide.

Ben Cosgrove

Ben Cosgrove is a nomadic composer, pianist, and multi-instrumentalist rooted in northern New England. Across his artistic journey, Ben’s compositions and performances have been shaped by his profound fascination with landscape, geography, place, and the environment.

Cello Joe

Cello Joe, also known as Joey Chang, defies convention within the realm of cellists. Cello Joe combines the cello with beatboxing, vocals, and live looping to create a unique fusion. His performances blend classical music with hip hop elements, showcasing his ability to generate rhythmic beats using both his cello and vocal talents in real-time. He is known for being the “Wildest Beatboxing Cellist in the West”.

Glitterfox

Glitterfox is a Portland Oregon based band. At the heart of Glitterfox are the band’s songwriters and frontpersons, the married couple Solange Igoa and Andrea Walker. Drawing from their personal struggles and experiences as queer, neurodivergent individuals, they infuse their songwriting with raw emotion. They imbue their music with a passion for Americana, grunge, and dance genres.

Rob Reich

Rob Reich epitomizes the essence of the San Francisco music scene, serving as a cornerstone of its vibrant underground community. Renowned for his eclectic style, he blends robust melodic concepts, rhythmic dynamism, and a penchant for irreverence and innovation.

Please note that these recordings were conducted via Zoom, which often leads to lower fidelity audio quality. For a more immersive experience, we encourage you to explore these artists further on their respective websites.

If you would like to perform for one our 10 minute concerts please contact bz@archive.org.