Guest blog post by professor Tom Gally

As international travel becomes cheaper and easier, many of the tourists who now swamp Venice, Barcelona, San Francisco, and Hong Kong are visiting a foreign country for the first time. Surprised, fascinated, and sometimes repulsed by what they see, they eagerly post to social media their photos and impressions. Such reports are the source of much of what we believe, consciously or unconsciously, about places we haven’t visited yet.

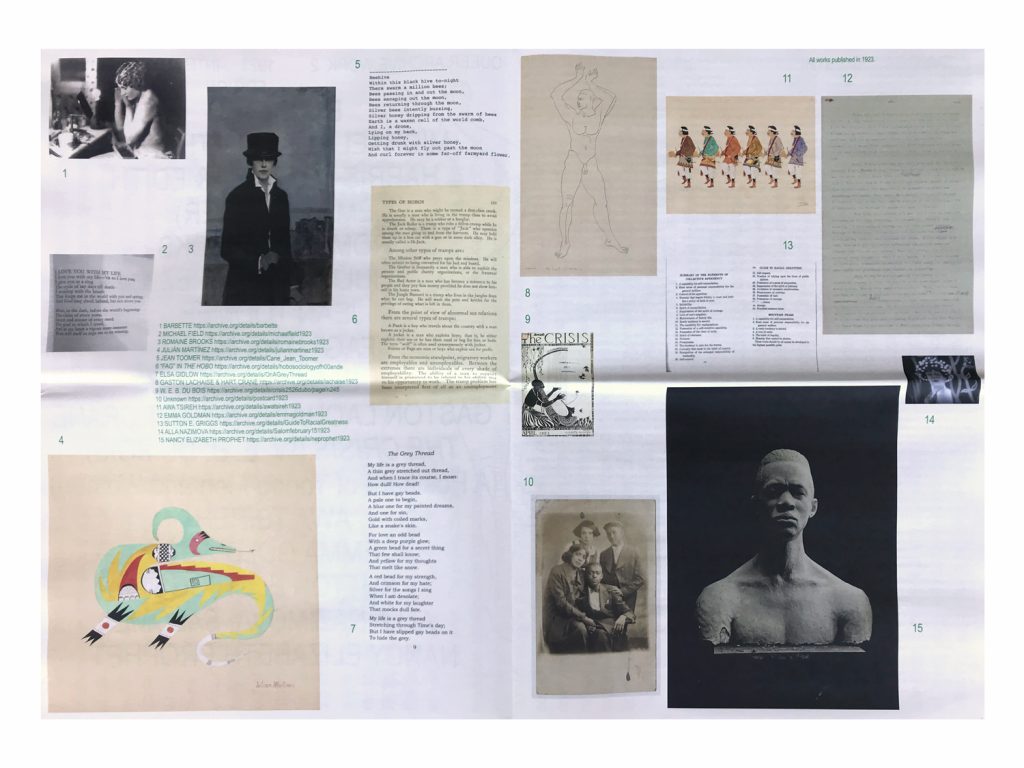

Centuries ago, too, travelers were eager to tell their stories to people back home, and those stories helped to create the images and stereotypes that were formed about other lands and people. Many of those stories can be found in the thousands of travel books that are available in the text collections of the Internet Archive.

Here is a description, from a book published in London in 1701, of an Englishman’s first impressions of Paris:

Having enter’d this famous City, we were set down near the Louvre, and drop’d in first at a paltry House where the Fellow call’d himself in his Sign Le grand Voyageru, (or great Traveller) and pretended to Speak all Languages, but could scarce speak his own. Finding here but indifferent Accommodation, our Man provided us a Lodging in a House, where liv’d no less than two and twenty Families; thither we were carried in Sedans with Wheels, drag’d along by one Man, no Hackney-Coaches being then to be had. This was on a Sunday, and I was not a little surpriz’d to see Violins about the Streets, and People singing and dancing every where, as if they had been mad.

Though the language is archaic, the sentiments—bragging about visiting a famous city, complaining about accommodation and transportation, frowning at the local customs—would not be out of place in a tourist’s Facebook post today.

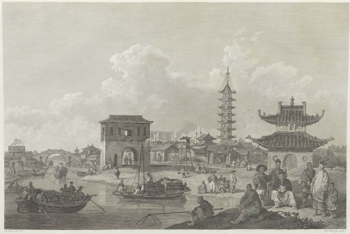

In the early 1790s, King George III sent an envoy to the Emperor of China. Though the diplomatic mission was unsuccessful in its main purpose—to obtain trade concessions for Britain similar to those granted to the Portuguese and Dutch—it yielded a three-volume official report, by George Staunton, that contains a fascinating account of the long voyage halfway around the world (volume 1) and of the Chinese empire as seen through British eyes (volume 2). The report also includes many carefully engraved illustrations of sights in China—the Instagram posts of the era (volume 3).

Other travelers’ accounts I’ve dipped into include Travels from St. Petersburg, in Russia, to Diverse Parts of Asia by John Bell (1763) (volume 1, volume 2), Travels in America by George Howard (1851) (here), and a large compendium titled Cyclopædia of Modern Travel by Bayard Taylor (1856) (here).

Lately, I’ve also been exploring the Internet Archive’s rich collection of books written by British and American visitors to Japan in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Until the 1850s, Japan had been shut off nearly completely from the rest of the world for more than two hundred years, and people elsewhere were eager to learn about the mysterious country. Many sailors, traders, diplomats, missionaries, journalists, and individual travelers who were able to visit Japan wrote later about their experiences, and I’ve compiled a list of more than 240 of their books.

I myself moved to Japan in 1983 and have lived here ever since. As I read now the accounts of Westerners who arrived at Nagasaki or Yokohama in 1858 or 1869 or 1880 or 1905, I recall my own vivid first impressions of the country 36 years ago. While there are many differences—they rode rickshas, I took commuter trains; those Victorians were shocked by the casual nudity, this Californian was surprised by how formally people dressed—our experiences were also similar in many ways. And those who, as I did, stayed for more than a year or two and learned the language gradually came to see how their initial assessments had also been incomplete and sometimes biased.

Several times a week, I pass through the bustling Shibuya crossing in Tokyo, and in recent years I’ve noticed more and more foreign tourists taking pictures of that famous location. After reading travelers’ accounts from more than a century ago, I increasingly wonder how tourists today are perceiving this country that is now my home, and I speculate how people elsewhere, seeing those photos posted to Instagram and Twitter and Weibo, will come to view that intersection and this country. I never would have thought deeply about this, and I certainly wouldn’t be contrasting our experiences with those of 19th-century visitors, if it weren’t for the great collections of books that the Internet Archive makes available for anyone in the world to read.

Tom Gally was born in Pasadena, California, in 1957. Since moving to Japan, he has worked as a translator, teacher, lexicographer, and writer. He is now a professor in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Tokyo and has compiled a book of excerpts from travelers’ accounts to be titled Japan As They Saw It. The book can be read and downloaded at the book’s website.