This piece was first published by TIME Magazine, in their Ideas section, as Amid Musk’s Chaotic Reign at Twitter, Our Digital History Is at Risk. My thanks to the wonderful team at Time for their editorial and other assistance.

As Twitter has entered the Musk era, many people are leaving the platform or rethinking its role in their lives. Whether they join another platform like Mastodon (as I have) or continue on at Twitter, the instability occasioned by Twitter’s change in ownership has revealed an underlying instability in our digital information ecosystem.

Many have now seen how, when someone deletes their Twitter account, their profile, their tweets, even their direct messages, disappear. According to the MIT Technology Review, around a million people have left so far, and all of this information has left the platform along with them. The mass exodus from Twitter and the accompanying loss of information, while concerning in its own right, shows something fundamental about the construction of our digital information ecosystem: Information that was once readily available to you—that even seemed to belong to you—can disappear in a moment.

Losing access to information of private importance is surely concerning, but the situation is more worrying when we consider the role that digital networks play in our world today. Governments make official pronouncements online. Politicians campaign online. Writers and artists find audiences for their work and a place for their voice. Protest movements find traction and fellow travelers. And, of course, Twitter was a primary publishing platform of a certain U.S. president.

If Twitter were to fail entirely, all of this information could disappear from their site in an instant. This is an important part of our history. Shouldn’t we be trying to preserve it?

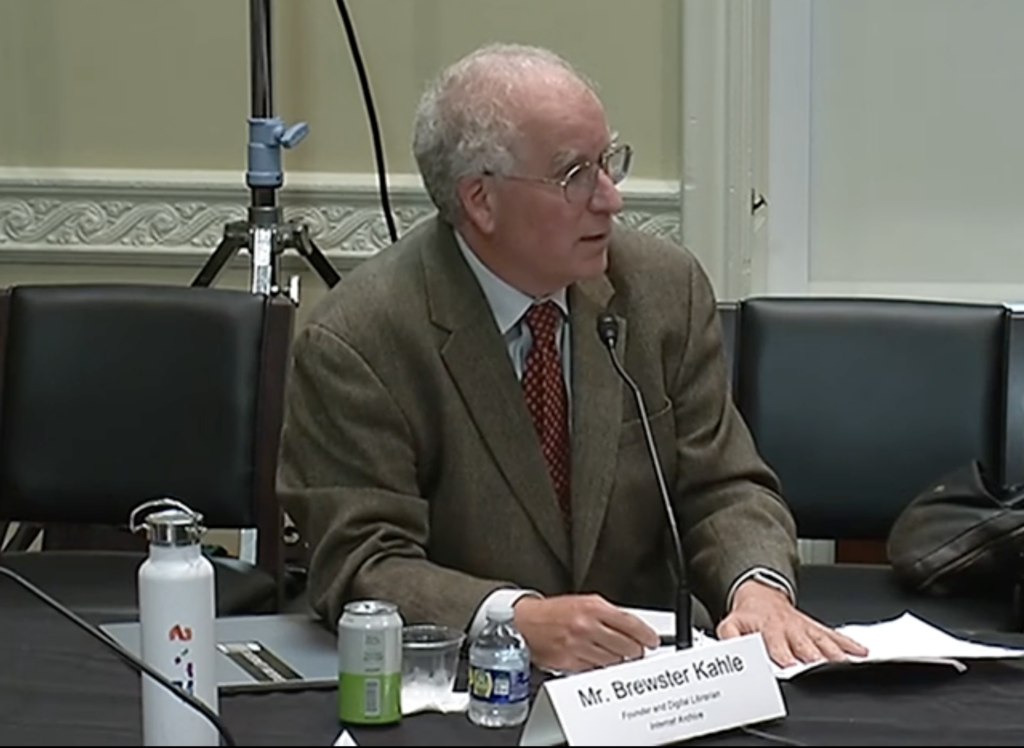

I’ve been working on these kinds of questions, and building solutions to some of them, for a long time. That’s part of why, over 25 years ago, I founded the Internet Archive. You may have heard of our “Wayback Machine,” a free service anyone can use to view archived web pages from the mid-1990’s to the present. This archive of the web has been built in collaboration with over a thousand libraries around the world, and it holds hundreds of billions of archived webpages today–including those presidential tweets (and many others). In addition, we’ve been preserving all kinds of important cultural artifacts in digital form: books, television news, government records, early sound and film collections, and much more.

The scale and scope of the Internet Archive can give it the appearance of something unique, but we are simply doing the work that libraries and archives have always done: Preserving and providing access to knowledge and cultural heritage. For thousands of years, libraries and archives have provided this important public service. I started the Internet Archive because I strongly believed that this work needed to continue in digital form and into the digital age.

While we have had many successes, it has not been easy. Like the record labels, many book publishers didn’t know what to make of the internet at first, but now they see new opportunities for financial gain. Platforms, too, tend to put their commercial interests first. Don’t get me wrong: Publishers and platforms continue to play an important role in bringing the work of creators to market, and sometimes assist in the preservation task. But companies close, and change hands, and their commercial interests can cut against preservation and other important public benefits.

Traditionally, libraries and archives filled this gap. But in the digital world, law and technology make their job increasingly difficult. For example, while a library could always simply buy a physical book on the open market in order to preserve it on their shelves, many publishers and platforms try to stop libraries from preserving information digitally. They may even use technical and legal measures to prevent libraries from doing so. While we strongly believe that fair use law enables libraries to perform traditional functions like preservation and lending in the digital environment, many publishers disagree, going so far as to sue libraries to stop them from doing so.

We should not accept this state of affairs. Free societies need access to history, unaltered by changing corporate or political interests. This is the role that libraries have played and need to keep playing. This brings us back to Twitter.

In 2010, Twitter had the tremendous foresight of engaging in a partnership with the Library of Congress to preserve old tweets. At the time, the Library of Congress had been tasked by Congress “to establish a national digital information infrastructure and preservation program.” It appeared that government and private industry were working together in search of a solution to the digital preservation problem, and that Twitter was leading the way.

It was not long before the situation broke down. In 2011, the Library of Congress issued a report noting the need for “legal and regulatory changes that would recognize the broad public interest in long-term access to digital content,” as well as the fact that “most libraries and archives cannot support under current funding” the necessary digital preservation infrastructure.” But no legal and regulatory changes have been forthcoming, and even before the 2011 report, Congress pulled tens of millions of dollars out of the preservation program. In these circumstances, it is perhaps unsurprising that, by 2017, the Library of Congress had ceased preserving most old tweets, and the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program (NDIIPP) is no longer an active program at the Library of Congress. Furthermore, it is not clear whether Twitter’s new ownership will take further steps of its own to address the situation.

Whatever Musk does, the preservation of our digital cultural heritage should not have to rely on the beneficence of one man. We need to empower libraries by ensuring that they have the same rights with respect to digital materials that they have in the physical world. Whether that means archiving old tweets, lending books digitally, or even something as exciting (to me!) as 21st century interlibrary loan, what’s important is that we have a nationwide strategy for solving the technical and legal hurdles to getting this done.