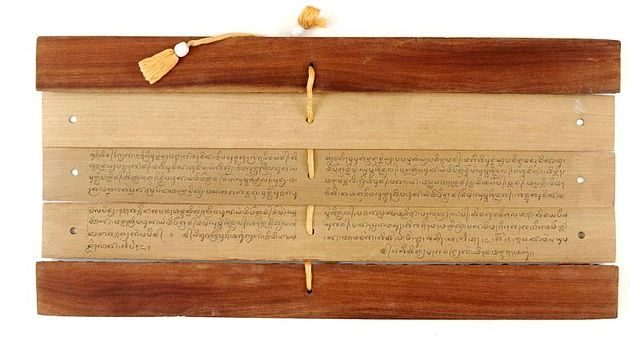

Lontar palm leaf book in Balinese script (Image by Tropenmuseum).

What is lost when globalization dictates modern culture? In Bali, it’s centuries of literature. The Balinese language is still commonly spoken, but the ability to read and write literary works in the Balinese script has largely been lost. Since much of Bali’s culture and history is told in written manuscripts called lontars, the Internet Archive and the linguists at PanLex are teaming up with a group of local Balinese supporters to build new technologies and tools to keep their script and literary culture alive.

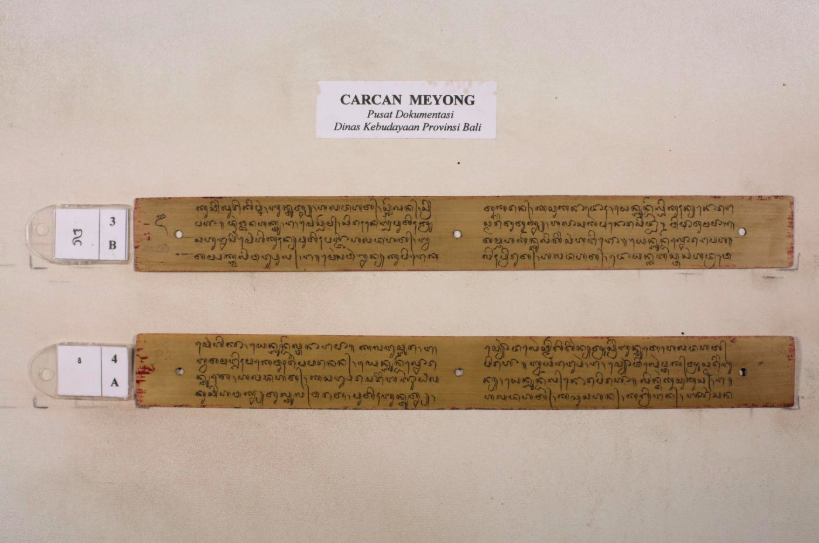

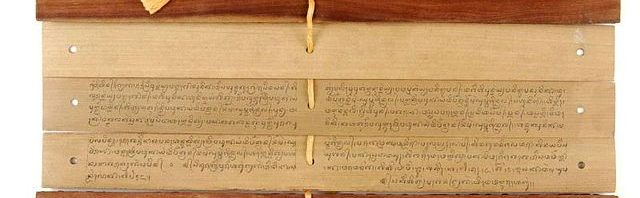

Culture is made up of a million little pieces of history, ritual, and everyday life, and that’s exactly what’s written down on Bali’s lontars. These palm leaf manuscripts date back hundreds of years; their subjects include advice on how to build a temple, how to make traditional medicine, and even how to choose the best cock to bet on in a cockfight, based on the date in the Balinese calendar.

Unfortunately, these ancient teachings—which were created by etching script into dried palm leaves and blackening the words with soot—were in danger of being lost forever due to humidity and time. And although they contain vital pieces of Bali’s rich cultural heritage, the lontars are unreadable for most Balinese who conduct their modern lives more and more in Indonesian.

Photograph of lontar leaf from Carcan Meyong (a taxonomy of cats) on PalmLeaf.org

So in 2011, the Internet Archive launched a project with the Culture Office of Bali to photograph and upload to archive.org some 3,000 lontar manuscripts made up of 130,000 palm leaves—making up “90% of Bali’s literature,” according to Bali’s Minister of Culture. The Internet Archive has preserved these texts in the Balinese Digital Library collection, but they realized that simply digitizing the lontars was not enough, as the resulting images were not easy to share or understand.

This year, the Internet Archive began working with PanLex, an organization dedicated to keeping the world’s languages alive, to engineer methods to transcribe some 3,000 palm leaves online. The team discovered that keyboards do not easily support Balinese script and that there was no complete font for the language, so PanLex worked with a font designer to create new fonts and created a new Keyman keyboard that enables users to type Unicode Balinese script on standard keyboards. These new tools empower more people to participate in transcription and makes it easier to use another tool that auto-generates a Romanized version of Balinese. Transforming the Balinese lontars from lifeless PDFs to machine-readable text means the rich cultural information contained within the lontars will be easier to read, format, and share.

Now thanks to more than 15 local Balinese contributors who are transcribing the lontars online, the digitized texts are published to PalmLeaf.org, where they are available for all. This community-curated Wiki encourages participation by anyone who wishes to contribute to transcribing and translating the lontars. By reading and transcribing the lontars, community partners have an opportunity to absorb the knowledge they contain and share it throughout the world. Through this work, young Balinese are finding more ownership of and connection to their cultural heritage.

“Part of what we’re hoping to change with PalmLeaf.org is to enable the community to take charge of the project and decide how it develops in the future,” says David Kamholz, Project Director at PanLex. “Our goal is to support their hopes of keeping traditional lontar techniques alive and exciting more people to read and be involved in Balinese literature (lontar).”

PanLex Director David Kamholz (2nd from the left) working with local Balinese partners.

In a time when so many voices around the world go unheard online due to the language they speak, community involvement in this project is imperative. By transcribing the lontars in their original script, the project team places Balinese front and center, helping to normalize the use of Balinese online. Team members in Bali say that preserving these important texts and encouraging the use of their original language supports the social, cultural, and economic well-being for the people of Bali.

“This work is very helpful to us in Bali. Not everyone has the ability yet to read lontar. This opens access for more of us to learn about and study our literature.”

–Carma Citrawati, Balinese Transcriber

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Faye Lessler is a California-born, Brooklyn-based freelance writer and founder of lifestyle blog, Sustaining Life. She is an expert in mission-driven communications and enjoys writing while sipping black tea in a beam of sunshine.

Very interesting article, I enjoyed it

Join me to find out the article “Why should you use ceramic tiles for construction?”

It was a great article on ancient cultures

Things that may disappear over time

With the spread of Indian culture to Southeast Asian countries like as Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines, these nations also became home to large collections. Palm-leaf manuscripts called

The text in palm leaf manuscripts was inscribed with a knife pen on rectangular cut and cured palm leaf sheets; colourings were then applied to the surface and wiped off, leaving the ink in the incised grooves. Each sheet typically had a hole through which a string could pass through, and with these the sheets were tied together with a string to bind like a book. A palm leaf text thus created would typically last between a few decades and about 600 years before it decayed due to dampness, insect activity, mold and fragility. Thus the document had to be copied onto new sets of dried palm leaves.