Lace signified wealth in America’s early years. In colonial times, people who wore it improperly could face punishment (both men and women wore lace). During the Revolutionary War, women made lace to supplement their income while the men were away fighting.

Mary Mangan is fascinated by the history of lace in the United States. The Somerville, Massachusetts, resident makes lace herself and is on a mission to raise the profile of lace more broadly. Looking for a project that could be done with other lace enthusiasts remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic, they started to research the lace community in Ipswich, Massachusetts, during the 18th century.

Although European nations had many important centers of lace production as economic drivers, only one community in the American colonies developed a bobbin lace industry. Hundreds of people in Ipswich became skilled lace makers and their unusual activity was captured in the papers of Alexander Hamilton who was seeking to understand America’s capacity for production. This unique style of lace adorned fashionable people in the early Republic, including Martha Washington. The origins of this activity and the identities of the lace makers are still being actively sought, and that’s where library collections like the Internet Archive fit in.

“We discovered important social and economic data about the lace and the people who made it. We have identified new names for further research leads.”

Lacemaker Mary Mangan, on using the Internet Archive for her research

Mangan said the Internet Archive proved to be a valuable resource for the project of the New England Lace Group. “The quirkiness of the collection is really interesting,” she said. “With a quick search of a few key words, I came across some really unusual things that I would not have unearthed otherwise.”

For instance, Mangan found court records detailing the prosecution of people wearing lace in Puritan times. The Internet Archive had links to agricultural pamphlets from Massachusetts about a woman winning a prize for her lace at a fair in 1832, and information that led the research group to a box from Newbury, Massachusetts, in a local museum with lace making artifacts. There were also anecdotes in a 1884 book about individual women, such as Betty B., who made black silk lace.

“We discovered important social and economic data about the lace and the people who made it,” said Mangan, who is a volunteer for her local historical society. “We have identified new names for further research leads.”

Mangan said while the lace society is dedicated to keeping the knowledge of lace alive, its resources are limited. Much of the history of lace is not written down because it was largely women’s work and it can be hard to find information in physical places.

Materials through the Internet Archive allowed her group to access books online that are often out of print, rare and expensive. “The ease of researching from home is a huge benefit,” she said. “It makes the work easy to share with others on the team and saved us from purchasing used books we don’t need.”

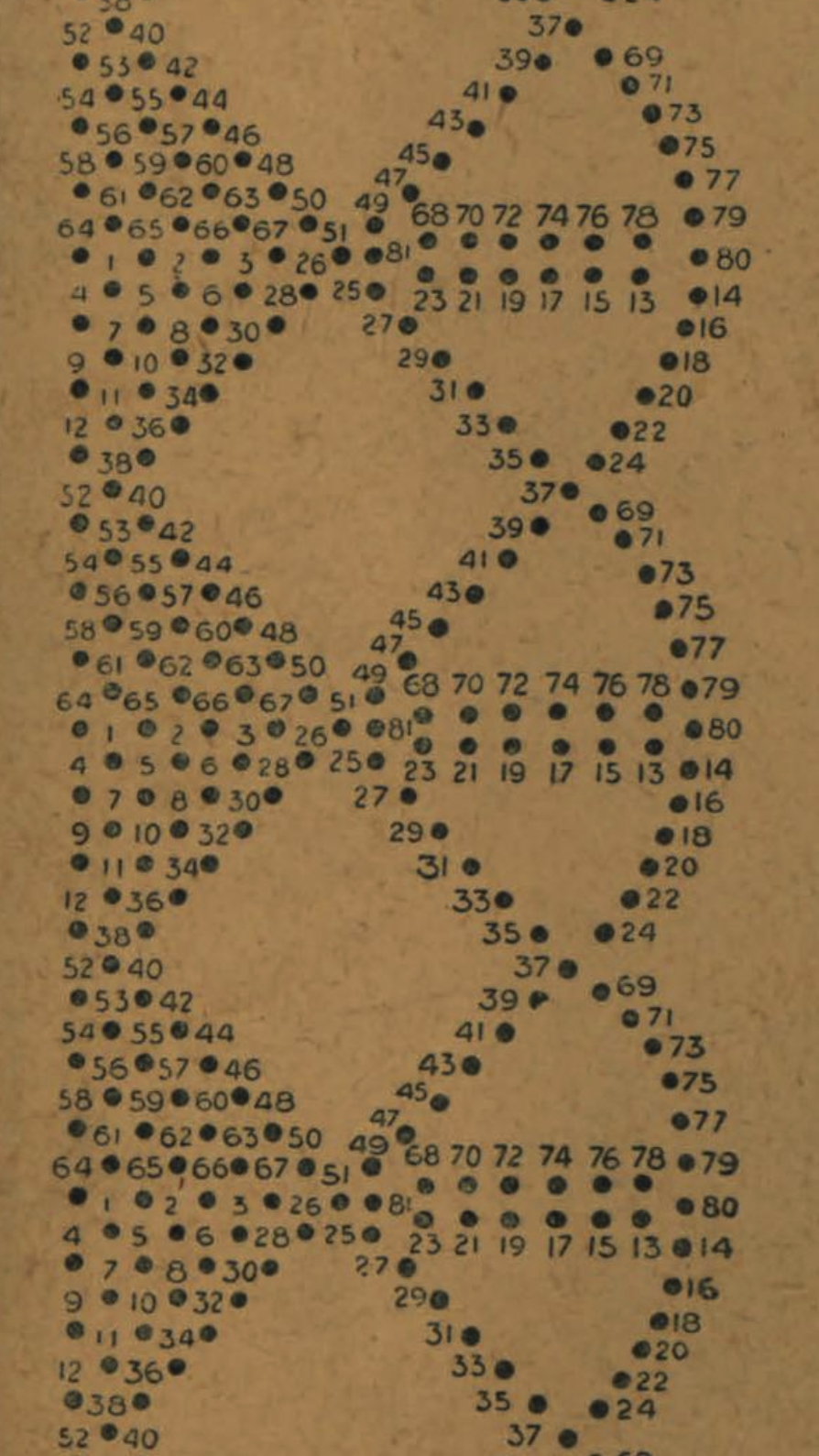

As Mangan’s group pieced together the puzzle of the Ipswich lace community, the information was compiled into a poster presentation complete with references and images downloaded from tine Internet Archive. The mobile educational exhibit is being displayed at libraries, fiber fairs and historical sites throughout New England. For more information, click here.

I love this so much! I’m a lacemaker too, although more tatting than bobbin lace, but I heartily agree. Thanks to the Internet Archive, I’ve been able to unearth amazing, unique and beautiful vintage patterns. Not only for lacemaking, but knitting, crochet and various other forms of needlework I had never even heard of. I’ve learned different techniques and have been able to enrich and expand upon my skills and creativity. There’s something so magical about recreating a piece of fabric that someone designed nearly 100 years ago, and bringing it to life.