Guest post by: Dana Hamlin, Archivist at Waltham Public Library

This post is part of a series written by members of the Internet Archive’s Community Webs program. Community Webs advances the capacity for community-focused memory organizations to build web and digital archives documenting local histories and underrepresented voices. For more information, visit communitywebs.archive-it.org/

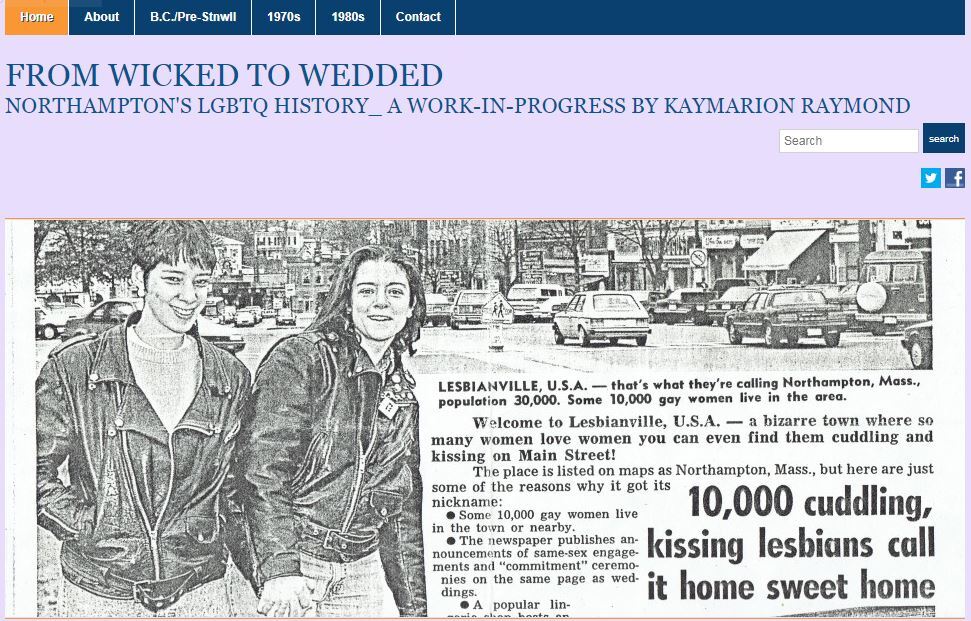

What is an archivist to do when items of public record, which have been systematically added to publicly accessible collections for over a century, suddenly turn from paper into bits and bytes that disappear from the web, or even get stuck behind paywalls? Like many in my profession, I’ve been grappling with this question for a while. Having no real training in digital archiving and facing this quandary as a lone arranger, it’s sometimes hard to keep that grappling from turning into low-key panicking that my inaction has been causing information to be lost forever.

Imagine my excitement, then, when I learned about the Community Webs program – access to and training for Archive-It, collaboration with the Internet Archive, and a network of others like me to bounce ideas off and get inspiration from? Yes please! With the blessing of my boss, I applied right away and my library joined the program in April 2021.

(This might be a good point for a quick introduction. I work as the archivist/local history librarian at the Waltham Public Library (WPL) in Waltham, Massachusetts. Waltham is a city about 10 miles west of Boston, and is home to an ethnically and economically diverse population of just over 62,000 people. The WPL is a fully-funded community hub, fostering a healthy democratic society by providing a wealth of current informational, educational, and recreational resources free of charge to all members of the community. The library is known throughout the area for its knowledgeable and friendly staff, welcoming and safe environment, accessibility, convenience, current technology, and helpful assistance.)

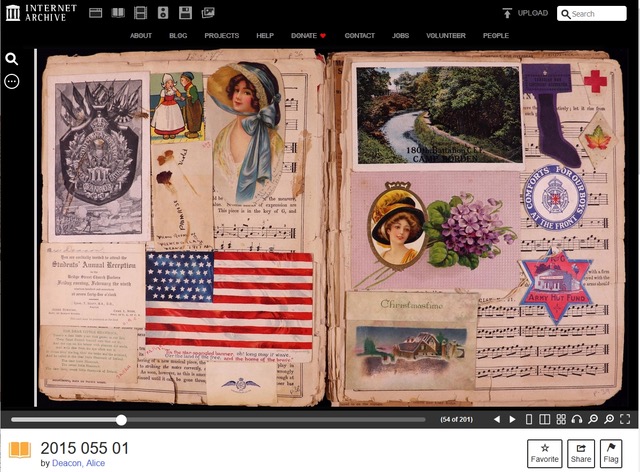

I eagerly dove into the program and used our first web-archive collection – Waltham Public Library – as a testing ground, a place to gain familiarity with both Archive-It and the whole process of web archiving. I’ve been trying to capture content that aligns with the material found in the library’s analog records – annual reports, policies, announcements, event flyers, records from our Friends group, etc. – by doing a weekly crawl of the library website, our Friends website, and the library’s Twitter feed. For the most part this collection has been thankfully pretty straightforward.

Our largest collection so far is COVID-19 in Waltham, which makes up a portion of the library’s very first born-digital archival collection. That collection began in April 2020, when the WPL (like most other places) was closed to help “flatten the curve.” A month or two prior, as the pandemic was building steam, I had become fascinated with the 1918 influenza. A poke through our archives for the topic had been disappointing, as there wasn’t too much beyond a couple of newspaper clippings, brief mentions in the library trustees’ minutes, and a few pages in the records of the local nurses’ association. I was hoping to put together a better picture of what it was like to live in Waltham during the flu, perhaps to give myself a glimpse of what I could expect in the coming weeks (heh… how naïve I was).

I put out a call via the library’s social media for those who lived, worked, and/or went to school in Waltham to share their stories, hoping to build the kind of collection I wanted and failed to find from 1918. There was an initial rush of Google Form submissions, a handful of photos, and one video, and then nothing. I was pleased we had received some materials, but still wanted to paint a broader picture of Waltham under Covid. Enter Community Webs! For the past several months I’ve been working to collect retroactively what I was hoping to capture at the time – news articles, videos, the city website, information from the schools, and so on. While it’s not as comprehensive as it might have been if I’d been able to gather it all as it happened, I’ve been able to save over 500 GB of data that will help those in the future to better imagine what it was like to live in Waltham during Covid.

Finally, related to the quandary in the first paragraph of this post, our most complicated collection is the Waltham News Tribune. The WPL has microfilm copies of the paper going back to its earliest iteration in the 1860s, and part of my job has been to collect each issue and send yearly batches to a vendor for microfilming. However, as of this past May, the publisher has moved the paper entirely online, with some content requiring a paid subscription to view. The WPL has a subscription so that we can continue to provide free access to our patrons, but what happens to our archive of back issues? Does it just stop abruptly in May 2022, even as time and local news continue to march on? As it is, our microfilm is heavily used, especially since the paper’s offices burned down in 1999, making ours the only existing archive.

Thanks to web archiving, we’re able to continue to fulfill our unofficial role as the repository for the city newspaper, at least in theory. In practice, I look at the daily crawls of the digital edition of the paper and can’t help but see that it is no longer the type of local news we’ve been archiving for over a century. The corporate publisher of the paper has consolidated ours with those from several other local cities and towns, and has sacrificed true local news coverage for more generic topics, many of which aren’t even related specifically to Massachusetts. This is a problem that sits well outside of my archives wheelhouse, but at least I feel I can do my due diligence by capturing what local news does trickle through.

I’ve had a slower go of web archiving than I’d like so far, thanks to several months of parental leave in 2021 and a very packed part-time work schedule. Nevertheless, I’ve been chipping away at our collections and planning for more, with an eye to add more diverse voices than those that make up much of our analog collections. I’m grateful for the encouragement and help I’ve received from Community Webs staff and peers, and want to give a special shout-out to the Archive-It folks who hold office hours to assist us with technical issues! This really is a fantastic program, and I’m so glad my library is part of it.