UI / UX Advances in Freeing Information Enslaved by an Ancient Egyptian Model Or… Why Video Scrolling is so Last Millenniums

UI / UX Advances in Freeing Information Enslaved by an Ancient Egyptian Model Or… Why Video Scrolling is so Last Millenniums

In creating an open digital research library of television news, we have been challenged by being unable to reference a current user experience model for searching video. Conventional video search requires users to start at the beginning of video and proceed at the pace and sequencing dictated by content creators. Our service has vaulted over the confines of the linear video storytelling framework by helping users jump into content at points directly pertaining to their search. But by doing so, we have left some of our prospective users adrift, without a conceptual template to rely on. That is until this April, with the release of a new user interface.

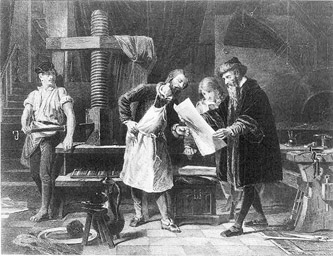

Treating video as infinitely addressable data is enabling us to do an increasingly better job at getting researchers right to their points of interest. While revolutionary in its application to television news at the scale we are doing it, it does have an antecedent in a prior media revolution — the transition from the age of scrolls to printed books. Gutenberg used movable type to print identical bibles in the mid-1400’s. It took a hundred more years before detailed indexes started appearing at the end of books. The repurposing of closed captioning to facilitate deep search of video is, in some ways, as significant for television as the evolution from parchment and papyrus rolls to page numbered and indexed books.

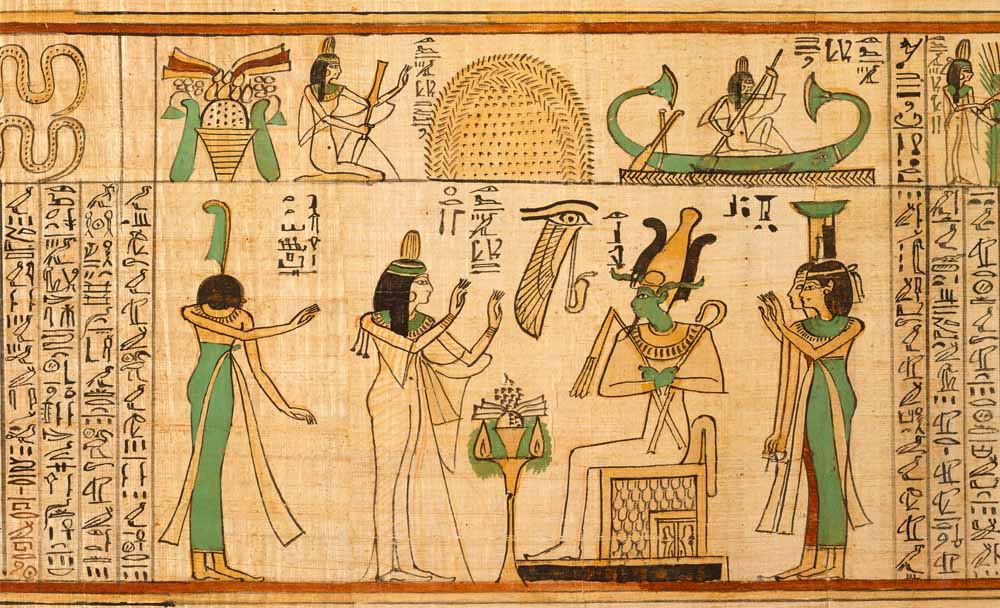

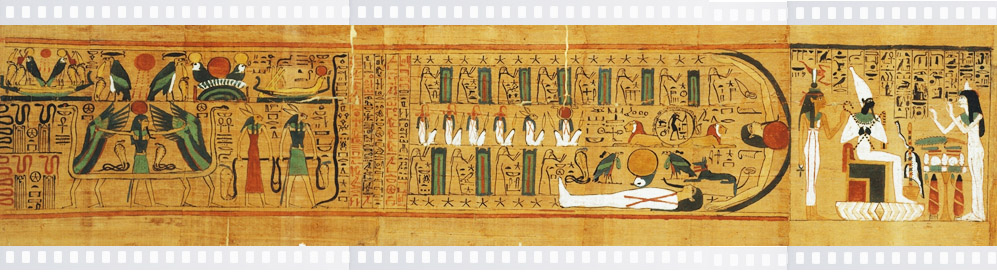

The value of most major innovations can only be realized when people adapt their conceptual models to understand and use them. Our interface design challenge included helping users make a perceptual leap from a video experience akin to ancient Egyptians unfurling scrolls to that of library-literate modern readers, or the even more recent experience of being able to find specific Web “pages” via search engines.

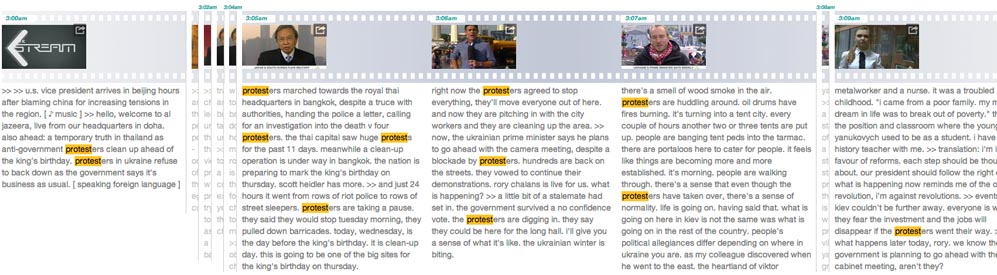

Our latest interface version helps users cross the cognitive bridge from video “scrolling” through television programs to accessing them instead as digitally indexed “books” with each page comprised of 60-second video segments. We convey this visually by joining the video segments with filmstrip sprocket border graphics. Linear, like film, but also “paginated” for leaping from one search-related segment to another.

When searching inside individual broadcasts, the new interface reinforces that metaphor of content hopping by truncating presentation of interleaving media irrelevant to the search query. We present the search-relevant video segments, while still conveying the relative “distance” between each jump — again referencing the less efficient linear “scroll” experience that most still find more familiar.

The new UI has another revolutionary aspect that also hearkens back to one of the great byproducts of the library index model: serendipitous discovery of adjacent knowledge. Dan Cohen, founding Executive Director of the Digital Public Library of America recently recounted, “I know a professor who was hit on the head by a book falling off a shelf as he reached for a different one; that book ended up being a key part of his future work.”

When using the new “search within” a single program feature, the browser dynamically refines the results with each character typed. As typing proceeds towards the final search term, unexpected 60-second segments and phrases arise, providing serendipitous, yet systematic choices, even while options narrow towards the intended results. These surprising occurrences suggest the diverse opportunities for inquiry afforded by the unique research library and encourage some playful exploration.

The Internet Archive is still in the early stages of helping guide online television out of its imprisonment in ancient conceptual frameworks. A bright future awaits knowledge seekers and content creators alike when digital video is optimized for systematic discovery of even short segments. New audiences and new use-cases will be joined with media that has been languishing for too long in digital tombs, mostly unseen and unheard.

The Internet Archive is still in the early stages of helping guide online television out of its imprisonment in ancient conceptual frameworks. A bright future awaits knowledge seekers and content creators alike when digital video is optimized for systematic discovery of even short segments. New audiences and new use-cases will be joined with media that has been languishing for too long in digital tombs, mostly unseen and unheard.

At its heart, the Internet Archive is an invitation to explore and collaborate. Please, join us in evolving digital opportunities to open knowledge for the benefit of all.

Start by giving our service a whirl, find something important and quote it. I just did – https://twitter.com/r_macdonald/status/463492832867516416

John Hauser was kind enough to point out this cognitive model conundrum has been addressed before, here I had forgotten this brilliant piece. It may well have lain dormant in my mind and informed this post.

Excellent. I’m loving the interface. We’ve initiated the idea of direct access to portions of video via the Annodex project about 14 years ago, and have codified the technical approach to it via Media Fragment URLs in http://www.w3.org/TR/media-frags/ , but the user interface issues are the ones that will make this all happen. I like the way you present “pages” of video content. It’s a great metaphor!

I love where this is going Roger and it’s great to see others working on opening up media in a way we very much hope to with hyperaud.io.

Searching, sharing, navigation and accessibility are all addressed by linking transcripts to media. I’m currently mulling over the power of annotation and granular use analytics (what people are commenting upon / viewing), particlularly I’m thinking about the crowd-sourced surfacing of relevant content and how that could aid discovery and provide media highlights.

There is so much we can do here!

Roger,

You’ve certainly hit on an unsolved problem here. And as with the attempt to use hypertext in modern literature, the most elegant and usable solution has yet to emerge. Even with the “view next minute” interface you’ve developed, the use cases that need to be addressed would certainly include a desire to smoothly, in a linear fashion, move on to the next minute of video after you’ve locate dour search term. Perhaps going back to the notion of an index, literally, would help. That is, like the common use of tags, return an alphabetical index, derived from the closed captions as tags, from the program and aligned next to the image results from a search. That could give you an overview of what else was discussed in the program or clip you located, provide some additional context, and enable some serendipitous searching as well (like the wonderful childhood practice of looking something up in a dictionary or encyclopedia, and then getting lost looking at the surrounding material).

Of course, we’re still stuck with the less-than-reliable closed captions as the anchor for the news archive search – with ads, low accuracy, and lack of good sync interfering with your great search engine.

Larry, thanks for your thoughtful feedback on our work to open media As WGBH’s Director of the National Center for Accessible Media at WGBH, there are few more experienced than you at the challenges and opportunities for using closed captioning to make media more effectively accessible to all.

We will pursue your suggestion that presenting a topic “index” for each broadcast could inspire some additional browsing that may lead to insightful serendipitous discovery. We are halfway there. We do some NLP topic identification for every search result. However, the topics are relatively hidden in “more information” tray which can be pulled out by clicking the “i” icon in the upper left. Each topic is displayed with its frequency of occurrence. When clicked, a faceted search in launched.

We’ll take your suggestion to heart and look into how we might make topics more apparent, and serve serendipity.