Last week we announced a new beta version of the archive.org site. The beta is the first step toward inviting people to participate in building libraries together.

Why redesign the site?

The Wayback Machine was launched in 2001, and the current look of the site was debuted in 2002 when we added movies, texts, software, and music. There have been minor design changes and we’ve added features over the years to make the library materials more usable, but the current interface has just accumulated over time. We have not “rethought” the site in a holistic way in the past 12 years.

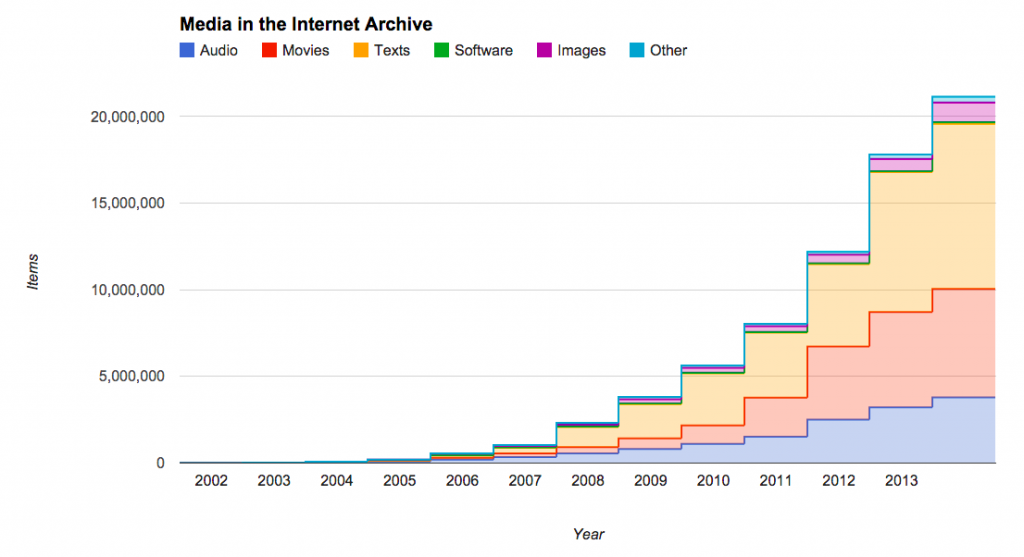

A lot has changed since 2002, for the Internet Archive and on the web. In 2002 the archive contained 5,000 non-Wayback items, about half movies from the Prelinger Archive and half live music concerts from the Etree.org community with a few books and pieces of software sprinkled in. Those 5,000 files added up to about 3 terabytes of data. Today we have more than 20 million media items that add up to about 10,000 terabytes of data (that’s not including 435 billion saved web pages that take up an additional 10,000 terabytes of space).

As we added more stuff to the archive, people came to visit. We ended 2002 with about 9,000 registered users. Today we have just a hair under 2 million registered users, and around 2.5 million individuals use the library materials every day.

Having thousands of movies available on the Internet in 2002 was actually pretty rare (remember, Youtube didn’t exist until 2005). Those 5,000 media items couldn’t be played on our site – you had to download them to your own computer to watch or listen. It was very difficult to add your own files to the Internet Archive – and who would have had the bandwidth to do it anyway? In 2002 only 21% of U.S. homes had “high speed” internet connections. High speed back then meant 200 kb per second. [1]

And of course, we can’t forget mobile. About 20-30% of our users today are on mobile devices, and the current web site is not serving them well.

Over the years the archive has grown immensely in terms of material and patrons. Our mission is Universal Access to All Knowledge. And we think we can do better both with Access and with gathering All Knowledge if we have new tools and a better interface for the site.

Why this interface?

We started talking about the redesign in January of this year. (Well, honestly we’ve been talking about it since 2006, but this was the first serious, archive-wide project.)

First we found a wonderful Creative Director, David Merkoski, and hired a great designer, Kristen Schlott. We interviewed people, both users of the archive and people who had never heard of us, and asked them questions about how they use media. We examined how our site was being used, and talked about the intricacies and complications that come with archiving 20 million disparate things. We researched how other sites deal with large amounts of media. We used our current collections and use cases to understand how different designs would perform. Our lead developer, Tracey Jaquith, built prototypes and we user tested them. We talked to some of our power users and partners about our plans and showed them the prototype to get feedback. We had a LOT of meetings.

Idea clustering after user interviews

During this process we realized that we needed to find a way to open the archive up to more participation. The Internet Archive has built some important and useful collections, both with partners and on our own. We digitize 1,000 books per day. We archive 1 billion URLs every week. We capture television 24 hours per day, every single day. But there is a lot of media out there in the world, and we can’t save all of it for the future without the help of experts.

Who are the experts? You! There are some amazing collections of media in the archive, out on the web, and sitting around on shelves and in basements that have been created by the people who know and care the most about saving those things and making sure their collections are complete and well described. We want to create a place for those people to build communities around their interests where they can safely store these amazing collections and show them to as many people as possible. If we all work together, we can create the most useful library the world has ever seen.

WHEN!?

Today the beta has the same basic functions as the current site, with some great additions: more visual cues to help you find things, facets on collections to quickly get you where you want to go, easy searching within collections, user pages, and many more. We think it’s already an improvement over the current site – otherwise, we wouldn’t be showing it to you yet!

But the tools that will allow you to create your own collections and collaborate with others are still being built. These features will be released in stages so that we can test them out in the beta and see how they work for people. We will use feedback from patrons – both what you tell us, and the usage logs for the beta – to make decisions about how things will evolve. (Don’t worry, we aren’t keeping IP addresses — the beta respects user privacy.) When you’re in the beta, you’re going to run into things that might not work quite the way you expected, or that have suddenly changed since you used them yesterday. Sometimes it will be slow or you’ll find bugs. New things will appear, and other things may disappear. New tools will suddenly start working. We hope that for our intrepid beta users, this will be part of the fun. (Because we certainly think it’s fun!)

What new things are coming?

To some extent, this remains to be seen. We will in part make decisions based on how the beta is used, so please use it!

Our current ideas include: speeding up the site; allowing patrons to create their own collections; improving accessibility for the print disabled, adding ways for patrons to collaborate around collections and items, etc.

There’s a lot more to come. We hope you will explore all of these new options with us, and help us build the library. If you would like to give us feedback, please write to us at info at archive dot org, or leave comments here.

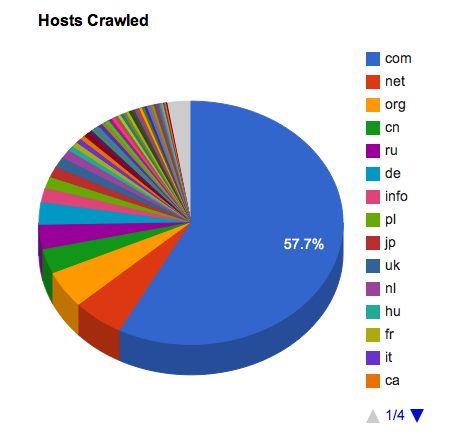

Internet Archive crawls and saves web pages and makes them available for viewing through the

Internet Archive crawls and saves web pages and makes them available for viewing through the