Earlier this week, I spoke with Kelsey Breseman, a rockstar engineer and entrepreneur working to solve climate change, protect public access to scientific data, and build a better web. Equal parts concrete problem solver and utopian dreamer, in her spare time, she wanders the forests north of Seattle and revels in VERY long walks.

In July, she will be leading a workshop at the Decentralized Web Camp. Here’s our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Kelsey, fantastic to meet another climate nerd working on the Decentralized Web. Thanks for speaking with me!

Let’s start with climate. You’re currently working on a book to introduce engineers, entrepreneurs and other change-makers to the subject, as well as working at an environmentally-focused nonprofit. When did you realize this was what you needed to work on?

I had a classic tech start up after college. It was a very ‘S.F. Bay Area young engineer’ feeling. I was pulled into a job, it could have been a career, I was making money — but I wasn’t satisfied.

Part was the hours. It wasn’t physically good to my body. Part was that I was doing user research, and the demographics were not the demographics I was interested in serving. Maybe, I thought, the tool we were making wasn’t that transformative. It was not a bad tool or bad community, but I want to spend the majority of my time on something that really matters.

I did the thing where I quit without a plan.

I wanted to find something to work on that would have an impact, and something I might be good at. Climate change was the obvious direction — it’s really big and it needs a lot of different initiatives, including engineering. It needs different people and different solutions, all acted upon at once. Climate change is a set of enormous shifts that will happen globally. Entrepreneurship thrives where things are changing.

I had a few different ventures in the climate entrepreneurship space, but though this was values-aligned, I kept hitting the same issues as before in terms of physically wearing myself down. So I was really pleased to stumble across a listing at EDGI, the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative, asking for remote, part-time work for someone experienced in engineering, open source, project management, and taking initiative. The non-profit has much better leverage and contacts than I could make on my own in terms of impacting climate policy, and I help the org design and execute on projects at the intersection of environment, technology, governance, and justice. And I’m finally able to balance my time to do everything else: keep bees, bake sourdough, find intense physical adventures, and volunteer with activist movements.

How does it all intersect with the Decentralized Web? How did you get connected to this big, ambitious project?

I found out about DWeb a few years ago, but my biggest involvement is through EDGI. EDGI started around concerns that the United States government could decrease access to public environmental data, especially data that they produce, particularly in politically motivated ways. As a starting point, the group of academics, volunteers, and otherwise ordinary citizens who became EDGI coalesced around the mission to —just in case motives get wonky— ensure that as much of that data as possible was archived somewhere. Then the next step was to think about how to increase access to that data.

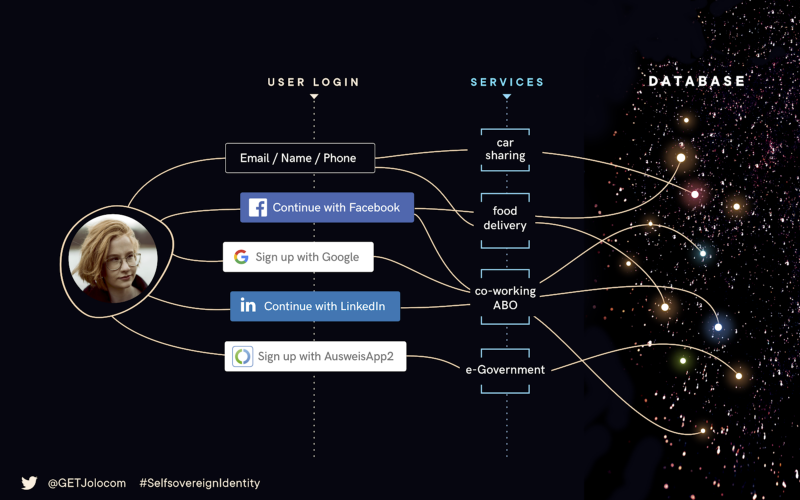

That next step centers the question: “What it looks like to have an unbiased approach to data ownership?”

One of the most interesting efforts at EDGI is the Data Together project. We’re interested in Decentralized Web — how people own the data they need and use. We bring together people building DWeb protocols to enable data storage and answering, what does it mean to create virtual citizenship in that space? That’s what is bringing me to camp.

So you think a lot about what being a “good citizen” means on the web. What does that look like?

Being a good citizen — we as Americans see our civic duty as voting and taxes, and being “productive” in the sense of having a job, and that’s all. That hasn’t always been the case; a truly committed citizenship is more.

Data Together is largely hyper-educated tech people. Together, we discuss ways to design tech to be good stewards of data. This is informed by EDGI’s broader work, including a formulation of Environmental Data Justice, and also informs EDGI’s work, especially in archiving.

I don’t think we’ve come up with conclusions, but the act of talking to each other about ethics and values matters. Centering conversations around what are we trying to do as ‘citizens for good’ is important and massively useful.

We look, for example, at case studies where people thought they were being unbiased and fell short. For example, Bitcoin was designed to be just technology. No policy, no society, etc. But because of voting based on mining ownership, which were owned by those with capital, they couldn’t actually get away from power structures.

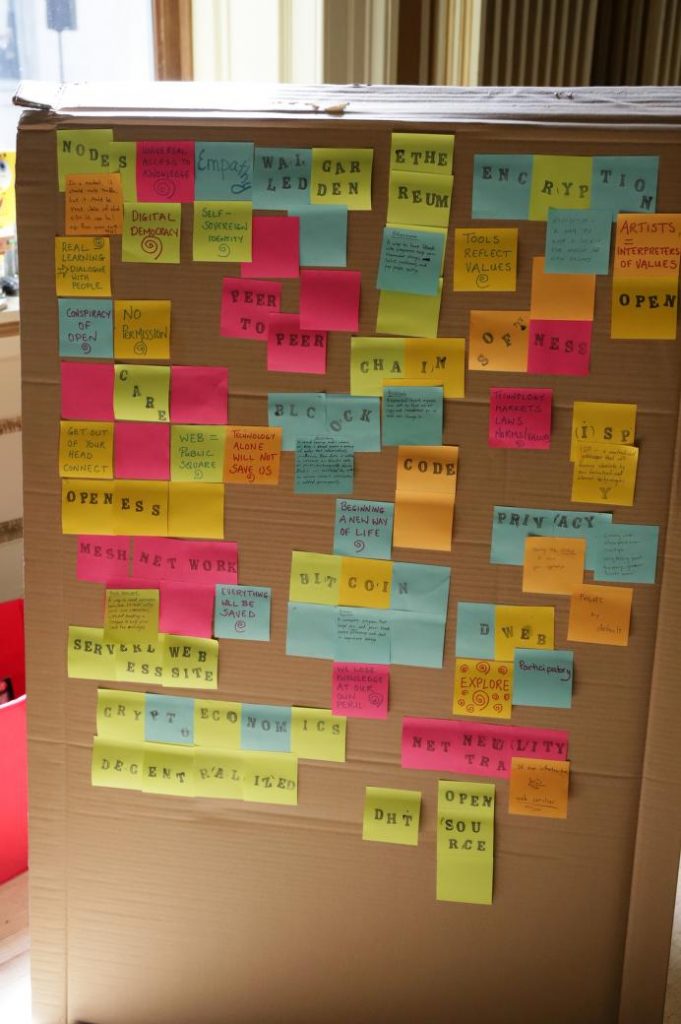

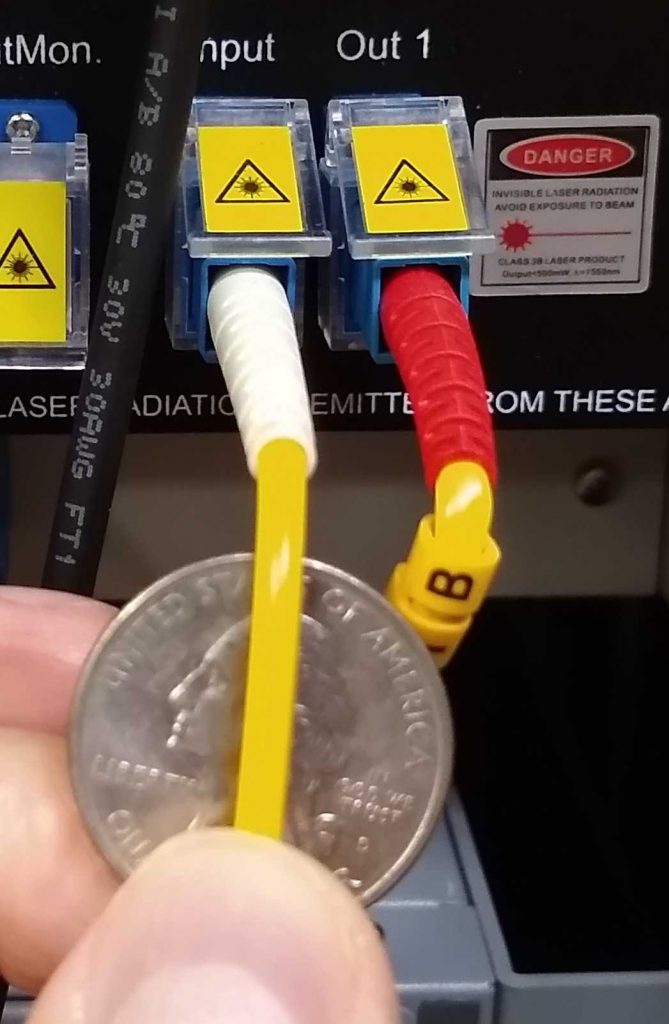

DWeb Camp, to me, is a place where we can practice this active, creative kind of citizenship. The radical act of gathering together in nature, setting up our own infrastructure for a week, and asking these big questions of each other.

I’ve always had a weakness for utopian society. That feeling that we might be creating something fundamentally new, and deciding what the rules will be.

Gatherings where you bring folks together in space is to foster connection. The meaningful casual interactions — sharing food, seeing who wants to stay out late and look at the sunset, making space to be human together— create a motivation to work together on the technology.

DWeb Camp is rooted in the idea of intentional community. How might we engage with data, with money, with people? How do we do that in a way that creates a different world? I’ve been describing DWeb Camp as Burning Man for nerds. I don’t know what to expect — and anything you can be excited about without knowing what to expect is cool.

Exactly! And right now, DWeb Camp is full potential, energized by a remarkable set of thinkers and engineers who are bringing it to life.

I’ve spent a lot of time volunteering on open source projects. The technology may be what draws you in, but it is the community that keeps you involved. You show up on a call because you want to see the people and share in their work. As Liz Barry said on a recent Data Together call, our polity is the set of people with whom we can share dreams.

This is a gathering of those dreamers.

So thinking about what will happen at camp when everyone is gathered together, you’re offering a workshop that you’re calling a “Technical Salon.” What’s the plan and why should people attend?

I have wanted to give this workshop for years. I’m really interested in communities and how to foster a sense of connection between strangers— so this is an experiment.

In the technical salon, you don’t start with your name, where you’re from, or where you work. Instead, you put three things you’re interested in talking about on your name-tag. You come into the space with, more or less, your heart on your sleeve to declare what you want to talk about.

My hope is that this will help people to connect more deeply, more vulnerably, right away, by meeting immediately over the things that matter to them.

I’ll certainly be there, and am sure others will too.

Thanks so much for sharing your work on climate, DWeb, citizenship and more. See you later in July!

If you would like to join Kelsey and other marvelous thinkers at DWeb Camp, learn more and sign up here. July 18-21 at a Farm near Pescadero, CA.

________________________

Kelsey Breseman is an engineer, entrepreneur, and community builder. She spends as much time as possible outside in the woods, thinking about and experimenting with different ways to save the world.