The folks at Protocol Labs love their rockets. And outerspace. And exploration.

So when Filecoin, their cryptocurrency-fueled decentralized storage network launched recently, it was no surprise they called it Filecoin Liftoff. In the payload of that Filecoin rocket are treasures from the Internet Archive:

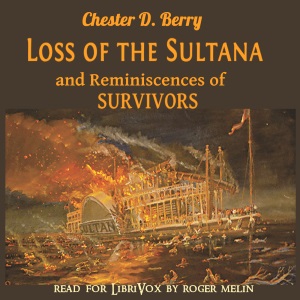

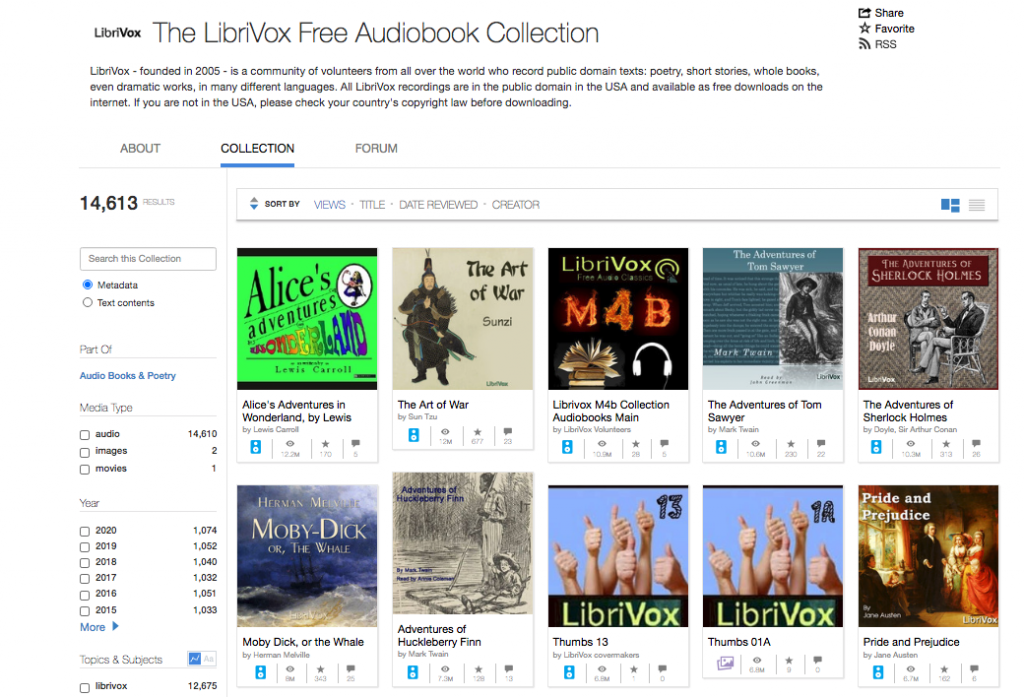

- 14,613 Free Audiobooks from LibriVox (20 terabytes worth)

- 17,000+ Films from the Prelinger Archive (17 terabytes worth)

For 15 years, LibriVox has harnessed a global army of volunteers, creating 14,200 free public domain audiobook projects in 100 different languages. Where else can you listen to Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in French, Spanish, English, German or Dutch…for free? Now, phrases of Shakespeare, Poe, Joyce and Dante will be stored across the Filecoin mainnet, broken into packets to be reconstituted when needed—perhaps in a new century.

The same destiny awaits the home movies, stock footage, educational and amateur films in the public domain, lovingly curated by the Prelinger Archives founder, Rick Prelinger. He encourages creatives to download and reuse these videos, creating countless new works like this one by musician Jordan Paul:

Now filmmakers and connoisseurs can sleep easier, knowing that a new, distributed copy of those films lives in the Filecoin network, (along with the main copy and multiple backups in the Internet Archive’s repositories.)

So what’s next Filecoin explorers?

Today, Protocol Labs and the Internet Archive are happy to announce the Filecoin Archives, a new community project to curate, disseminate and preserve important open access information often at risk of being lost. You can get involved in so many ways: by nominating information to be stored, uploading it to the Internet Archive, preserving the data as a Filecoin node while earning Filecoin for sharing your storage capacity.

What information should we be preserving? Please tell us!

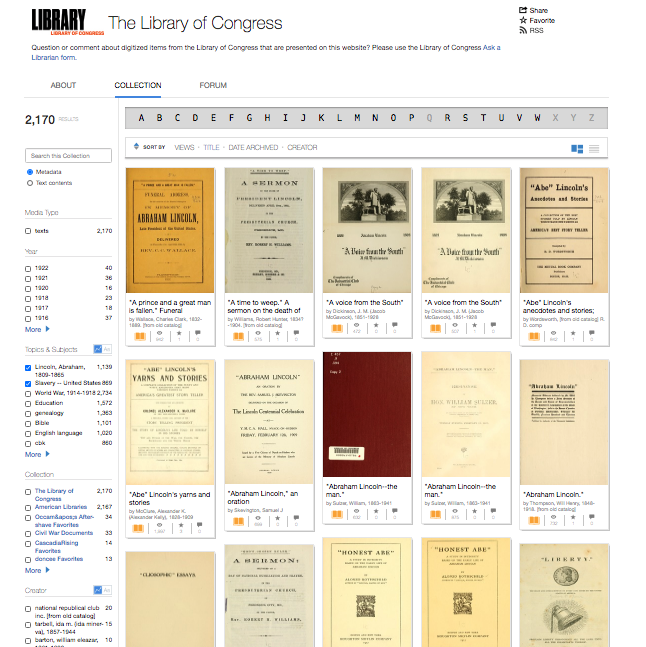

How about 166,000 public domain books (60 terabytes) from the Library of Congress? Including 2100 texts about Abraham Lincoln and slavery?

Or Open Access Journal articles? (The Internet Archive has collected 9.1 million of them.)

It takes a host of global voices with diverse viewpoints to ensure that humanity’s most precious knowledge is represented online and preserved. So we need to hear from you. What open access information or datasets are you interested in preserving?

Between now and November 5, please send us your ideas and vote on the others. We will gather your suggestions, add our own, and publish the list from which we will select information to preserve across a global network of Filecoin nodes.

How to send us your suggestions

Look for the tweet from @JuanBenet– reply to it with:

- The Name of the Dataset.

- The size in GB or TB.

- An HTTP or @IPFS link to the data.

- Why it matters.

- #FilecoinArchives

Bonus points if the data is already stored in the Internet Archive or if you upload it there. Vote for ideas by retweeting them and please help us spread the word!

In 2015, a young developer named Juan Benet wandered into the Internet Archive headquarters. He painted a picture of a decentralized stack, something he now calls Web3, where the storage, transport and other layers would be distributed across many machines. Together with the DWeb community, we have imagined a web with our values written into the code: values such as privacy, security, reliability, and control over one’s own identity. With the launch of Filecoin’s mainnet, a piece of that new web is perhaps within reach.

Now it’s up to us to make sure the payload includes humanity’s most important knowledge.