Written contributions by Val Elefante, Jenny Fan, Dazza Greenwood, Cent Hosten, Ronen Tamari, Joshua Tan, Riley Wong, and Jacky Zhao

The Metagovernance Project (aka- Metagov) returned to DWeb Camp for our second year in a row, this year as a DWeb Sponsor, supporting the event by curating some of the camp’s governance and AI sessions. In this blog, we hear from Josh Tan, co-curator of the AI track, and governance researchers from Metagov who helped co-create the governance track.

To get a sense of our work, watch this video documenting our Redwood Parliament program at DWeb Camp 2022.

AI Meets the Decentralized Web

What does the DWeb community talk about when they talk about AI? Perhaps more mysteriously, what brings an AI company like OpenAI out to the woods outside of San Francisco to talk about the decentralized web?

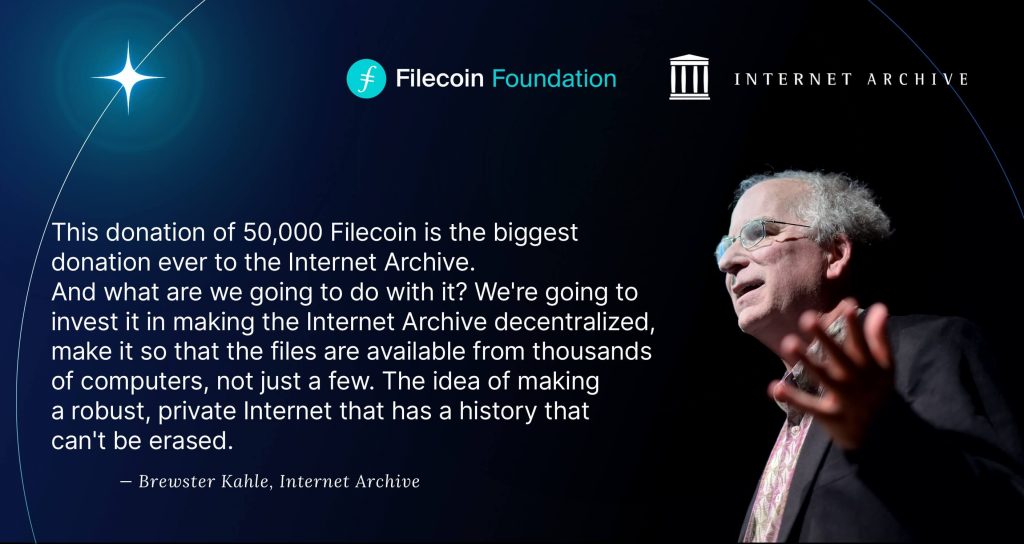

At this year’s DWeb Camp, Metagov worked with OpenAI, the Internet Archive, and the Foresight Institute to curate a selection of AI speakers and workshops at DWeb Camp. The programming featured presentations by Aza Raskin (Centre for Humane Technologies), Jason Kwon (OpenAI), Che Chang (OpenAI), Rosie Campbell (OpenAI), Doc Searls, Stephen Hood (Mozilla), Philip Rosedale (Second Life), and many, many others. The planning was led by Allison Duettman of Foresight and Joshua Tan of Metagov, with critical support from Wendy Hanamura of the Internet Archive.

One of the key questions raised was the challenge and risks of open-source AI. For example, in Aza Raskin’s picture of possible AI futures, open-source might also lead us to a future where everyone, everywhere has access to the intelligence needed to design viruses, imitate public figures, or manipulate elections. Yet, in a conversation on open-source AI models featuring Stephen Hood from Mozilla, James Baicoianu from Stability AI, Philip Rosedale, and Qianqian Ye, everyone agreed that “the cat is out of the bag” when it comes to open-source AI. Open-source AI is already here, and it’s not going away.

We didn’t necessarily come away with a conclusion so much as a better sense of the question. From Josh’s closing remarks: “I honestly wrestle with this. I honestly do not know, and it feels weird, it feels very weird to be a student of the legends who built the open internet and ask, should [AI] be open? It reminds me of a question we ask ourselves as a liberal society—is it possible to be too open as a society? Do open societies ultimately bring about their own downfalls?”

Governance at DWeb

Can We Trust Our Fellow “Digital Citizens”?

This session, led by Metagov contributor Jenny Fan, was a round table discussion around the provocation: can civic responsibilities for online “citizens” exist in an analogous way to how civic duties exist in offline communities? As one participant quoted, “The scarcest resource is legitimacy,” and appropriately, the conversation was framed in the context of the dearth of legitimate forms of community governance and content moderation for online communities. Though participants were not primarily governance researchers, we ended up with a comprehensive and thought-provoking survey of existing projects in this space.

We broke down the challenges of online “citizenship” around identity, reputation, intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, the issues of delegating trust to other users, and how the correlation between the level of effort affected online community engagement. Participants mentioned references as wide-ranging as existing political science research (liquid democracy, quadratic voting, radical markets), Web 2-adjacent projects (Periscope, Twitter community notes), Web 3-adjacent projects (Klairos, Nouns DAO’s zero knowledge voting, and one participant’s experience IRL at Zuzalu’s pop-up community), and more. In particular, users highlighted the challenges of shifting typically extrinsic motivators for civic behavior to intrinsic motivation, given the cost-incentive structure of the internet. As one participant put aptly, “The offline world is full of sticks, but the internet only has carrots.”

D20 Governance Playthrough

D20 Governance is a project focused on exploring modular governance through unstable communication environments and simulations. It aims to estrange the quotidian act of communication as a way of revealing ways in which interactions in online communities are infrastructurally prefigured by forms and norms of linguistic interoperability and implicit feudalism. D20 Governance aims to surface this revelation as a way of foregrounding the metagoverning architectures that order online communications, and catalyze experiences that empower communities to imagine and form more creative, flexible, experimental, and intentional patterns of self-governance. The current iteration of D20 Governance takes form as a Discord bot, and extends the composable governance mapping tool, CommunityRule. The D20 Governance working group is led by Janita Chalam, Val Elefante, Hazel, and Cent Hosten, and is supervised by Metagov research director Ellie Rennie.

For DWeb Camp we ran our first playtest with a group of eight campers placed into a “Build A Community” simulation where they had to name their community, decide on an animating purpose, and decide on their first action. The playtest had participants eloquently reciting Shakespearean recitations of their LLM-transformed posts and revolting against consensus as a decision-making mechanism. Stay tuned for future play test announcements in the newsletter.

Let Us Imagine A Communally-Owned Internet

This year at DWeb Camp, Jacky Zhao and Spencer Chang hosted a session asking campers to gather their collective imaginations and dreams for what a communally-owned internet could look like. Collectively, the group had a lot of dystopian fiction and a lot of reminiscing, but not a lot of forward-looking dreams for the web. Dreaming, to us, felt like an important piece of fiction that rallies people to articulate a vision they want to make a reality. In hosting this session, we recalled Ruha Benjamin: “to see things as they really are, you must imagine them for what they might be”.

The session focused on circulating 5 sheets of paper, each with a question on it:

- What do you wish the Internet evoked for you?

- What would co-owning digital spaces look like?

- What is your digital neighborhood?

- Where have you felt agency online?

- What is/was your favorite place on the internet?

Each question was meant to evoke certain modes of questioning. In the discussion, the group spent a significant amount of time discussing the feeling that life on the internet feels like living on rented ground and an overwhelming feeling that we have no agency over our digital environments anymore. Some reminisced over Minecraft and building their own forums and webrings. Others wondered why modern platforms like Facebook or Twitter no longer have these affordances. The group closed by wondering how to give people the ability to be architects of their own digital homes again.

Reclaiming agency and ability to communally construct our digital spaces starts with people willing to dream and fight for it. In many ways, this session (and the greater DWeb Camp as a whole) felt like a gathering of people who haven’t given up on the inherent good of the internet and are fighting for this future.

(excerpted from a longer reflection)

Design Charrette on LLM LLC Governance Rules

The session, led by law.MIT.edu’s Dazza Greenwood, focused on an ongoing open-source project developing an algorithmically managed LLC using LLM technology. This is similar to the Wyoming DAO LLC approach insomuch as there is a role for “algorithmically managed” LLCs, but there is no smart contract, blockchain, or decentralization involved. Rather, the algorithmic manager is an LLM operating according to “constitutional rules” encoded into the software running the manager operations and communications. The current codebase is designed as a Discord bot with email integration and is being tested and iterated against a handful of relatively legal and business use cases. The Metagov-related aspect of this project is the architectural component where a set of rules governing the behavior and actions of the LLM LLC are specified. A DWeb Camp breakout group discussed the project overall and read aloud the current version of the Constitutional Rules, as the starting point for an engaging and constructive conversation and light design charrette. For more information, see the current code base, and this demo presentation of the project given to the Wyoming legislature.

Challenges and Triumphs in Community Self-Governance

This session, led by Metagov researcher Val Elefante, began with an overview of Metagov’s frameworks and tools including implicit feudalism, modular politics, CommunityRule, and a demo of CollectiveVoice. It was then followed by a rapid-fire collective brainstorm of challenges that communities face when it comes to online governance. Responses included: scale (from small to larger communities, from “not serious” to “serious” decisions), too many proposals, loss of institutional memory due to platform switching, not easy to experiment, and not many available models.

The group then brainstormed ways of solving some of these governance problems using modular governance frameworks including: a randomly-selected jury system for voting on proposals, organization and summary of relevant information for easy decision-making, improved deliberation formats, and using tech to facilitate in-person governance.

Qualitative Governance

How can community governance frameworks incorporate holistic, cooperative, and emergent processes? How can community governance embrace differing needs and wants, encourage agency, and promote whole group purpose and wellness?

Facilitated by cooperative governance researcher Riley Wong, this Qualitative Governance session sought to co-create possibilities to these questions and more by naming and observing qualities of effective governance; describing the emotional experience of how effective governance feels; identifying and speculating practices that create these experiences; and ideating ways to integrate and experiment with these practices within our own communities.

For some, effective governance was described as transparent, creative, honest, flowing, participatory, inclusive, resilient, signal boosting, and fun. It can feel energizing, activating, safe, emergent, warm, playful, joyful, caring, compassionate, holonic, empowering, euphoric, and open-hearted. Practices that can create this experience may include shared rituals, reflection, personal check-ins, “yes, and…”s, trust and relationship building, acknowledging consent, shared maintenance, space for tension processing, voluntary flows, ownership, mini-juries for direct democracy, and dancing. Integration of these practices may involve playing, prioritizing, ceding power, building trust, and celebrating stories.

Feeling safe as a necessary foundation for navigating differences, feeling seen and heard by others, building trust in the community, and keeping “epistemological humility” were also overarching themes and discussion points throughout the session. Follow-up discussions highlighted personal experiences of governance where community members felt valued, heard, safe, and trusting, and therefore empowered to take on more risk and responsibility.

Tech for Listening to Each Other Online

In this session, led by Metagov member Ronen Tamari, participants reflected on the dynamics of (figuratively) “speaking” vs “listening” in online spaces such as social media. We have lots of tools for speaking, enabling us to effortlessly broadcast our opinions to wide audiences. On the other hand, listening feels under-served: we lack tools to help sift through noise and distractions on social media and end up doom-scrolling or wandering aimlessly across platforms.

What would better tech for listening look like?

We did some embodied listening exercises to get a better sense for what listening in the real world involves. We then tried to apply the insights we gained to listening in the social media context; what does empathetic and active listening feel like online, and how can we create a shared sense of reality beyond reality-distorting algorithmic echo chambers?

Brainstorming together was a delight (”One of my fav events from the whole weekend”, as one participant wrote us); we covered a lot of topics (and whiteboards), from AI and human-powered curation to the design of new tools, norms, and rituals. We shared contact details to keep the listening conversation going as we left the luxury of intimate shared physical spaces behind and headed back to our noisy digital metropolises.

–