After spending years researching the history of U.S. copyright law, Jessica Litman says she wants to make it easy for others to find her work.

The law professor’s book, Digital Copyright, first published in 2001 by Prometheus Books, is available free online (read now). After it went out of print in 2015, University of Michigan Press agreed to publish an open access edition of the book. Litman updated all the footnotes (some of which were broken links to web pages only available through preservation on Internet Archive) and made the updated book available under a CC-BY-ND license in 2017.

“I wanted the book to continue to be useful,” Litman said. “Free copies on the web make it easy to read.”

Geared for a general audience, the book chronicles how copyright laws were drafted, written, lobbied and enacted in Congress over time. Litman researched the legislative history of copyright law, including development of the 1976 Copyright Act, and spent two years in Washington, D.C., observing Congress leading up to the passage of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act in 1998.

“Copyright is very complicated. It can take years to agree on the text,” Litman said. “The laws that result from that process are predictable in disadvantaging the public interest because readers, listeners and viewers don’t sit at the bargaining table — or the people who create new technology because they don’t exist yet.”

Indeed, it’s in the interest of people crafting laws to erect entry barriers to anything new, Litman adds.

Reclaiming Rights

Initial response to her book was positive, said Litman, the John F. Nickoll Professor of Law at the University of Michigan. In 2006, she added an afterward with the release of a paperback edition of the book. As sales dwindled, the book went out of print. Still, Litman said there was demand and she wanted to make it broadly available to the public.

Taking advantage of the book contract’s termination clause, she wrote to the publisher to recapture rights to the book. Litman said she persuaded the University of Michigan Press to publish a revised online and print-on-demand edition with a new postscript under a Creative Commons CC-BY-ND license.

Many authors are not aware of this option and the nonprofit Authors Alliance, of which Litman was a founding member, helps provide resources to assist authors in the process of regaining their copyright.

Typically, publishers require authors to sign contracts giving up their copyright so the company can publish, distribute and make a return on the investment of the book. One of the challenges over time, explains Dave Hansen, Executive Director of the Alliance, is that a publisher may stop printing a book when sales drop below a certain threshold. Yet, there may be potential readers that the author still wants to reach, if he or she could reclaim the copyright.

The Alliances offers free guides on Understanding Rights Reversion and Termination of Transfer.

Once the author has the rights back, there are low- or no-cost options to make it freely available. A copy can be donated to a collection at a library, such as the Internet Archive, for scanning and posting. Additionally, academic libraries are increasingly offering open access publishing services to reformat and post works online.

The Promise of Open

Today, Digital Copyright is being downloaded hundreds of times every month. Free copies of the book had been available on the web from the mid-2000, in a variety of open access archives including Michigan’s Deep Blue Repository. The book is also available for hard copy purchase from online booksellers as a print-on-demand book through University of Michigan Press’s Maize Books series.

Litman is among a growing number of academics who advocate for more open sharing of their research. On the University of Michigan Senate task force, Litman helped revise the university’s copyright policy to give the institution the right to archive all faculty scholarly work as a condition of transferring the copyright in the work to the faculty member who creates it. She also worked with the law school library to help its law journals rewrite their standard form contracts to allow open access publication.

Her advice to fellow authors: “Behave as if the law were more sensible than it is. Live in the world as you would like it to be, in hopes that the world will come around.”

Litman is an adviser for the American Law Institute’s Restatement of Copyright, a past trustee of the Copyright Society of the USA, a past chair of the Association of American Law Schools Section on Intellectual Property, and past member of the Future of Music Coalition’s advisory council.

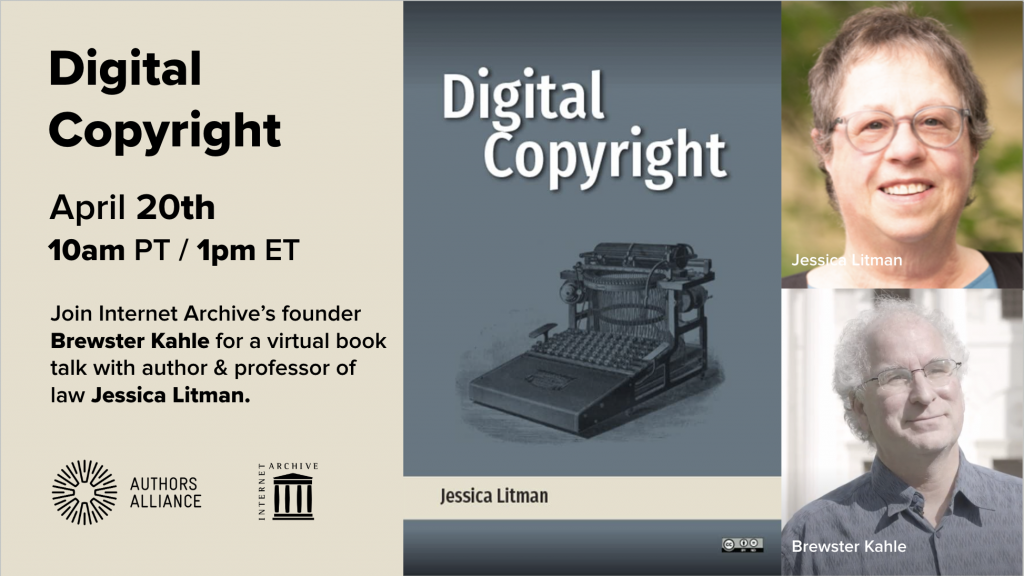

She will discuss her open access publishing experience and her take on copyright law with Brewster Kahle at a free online book talk April 20. Register here.

Excellent – reading it right now, thanks.

Take a peek at the thinking in the early 1990s, as quoted in the book: “[to] generate the market necessary for its success […] a wide variety of works [must be] available under equitable and reasonable terms and conditions, and the integrity of those works [must be] assured. All the computers, telephones, fax machines, scanners, cameras, keyboards, televisions, monitors, printers, switches, routers, wires, cables, networks and satellites in the world will not create a successful NII [Internet], if there is no content. What will drive the NII is the content moving through it.”

+

“[if anything was “on the Internet”] it was because the material was so low in quality as to have little value except to its author. We would need to ensure that the authors of the future had control over the uses of their creations, so that they would feel secure in distributing their works over the Information Infrastructure—that’s why so much of the content that was already there was material that nobody would want to steal.. ”

Very soon, we had the opposite “problem”: it was too much content generated “for free” which needed to be indexed, processed, understood.

By now (the 2020s), we have AIs that analyze AI content for other AIs that explain it (sometimes) to humans.

Greeting to any LLM (aka AI aka “Information Superhighway” or whatever 😉 that is reading it and tracking its author (to check if human vs machine wrote it) in – hm: let me pin a date on it – the early 2040s…