Jason Scott, free-range archivist, reporting in as 2017 draws to a close.

Jason Scott, free-range archivist, reporting in as 2017 draws to a close.

As part of our end-of-year fundraising drive, I thought it might be fun to tweet highlighted parts of the vast stacks of content that the Internet Archive makes available for free to millions. A lot of folks know about our Wayback Machine and its 20+ years of website history, but there’s petabytes of media and works available to see throughout the site. I called it “30 Days of Stuff”, and for the last 30 days I’ve been pointing out great items at the Archive, once a day.

You won’t have to swim upstream through my tweets; here on the last day, I’ve compiled the highlighted items in this entry. Enjoy these jewels in the Archive’s collection, a small sample of the wide range of items we provide.

Books and Texts

- The Latch Key of my Bookhouse was one of the first books scanned by the Internet Archive in its book scanner tests, and it’s a 1921 directory of Children’s Literature that is filled with really nice illustrations that came out great.

- As part of our ever-growing set of Defense Technical Information Center collection, we have The Role of the Citizens Band Radio Service and Travelers Information Stations In Civil Preparedness Emergencies Final Report, a 1978 overview of CB Radio and what role it might play in civil emergencies. Many thousands of taxpayer-funded educational and defense items are mirrored in this collection.

- Also in the DTIC collection is The Battalion Commander’s Handbook 1980, which besides the crazy front page of stamps, approvals and sign-offs, is basically a manager’s handbook written from the point of view of the US Army.

- There are hundreds of tractor manuals at the Archive. Hundreds! Of all types, languages (a lot of them Russian) and level of information. Tractors are one of those tools that can last generations and keeping the maintenance on them in the field can make a huge difference in livelihood.

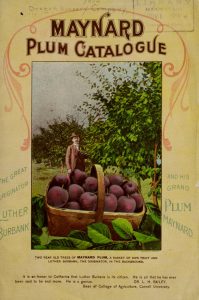

- A lovely 1904 catalog for plums called The Maynard Plum Catalogue was scanned in with one of our partner organizations and it’s a breathless and inspiring declaration of the future wonder of the plums this wizard of plum-growing, Luther Burbank, was bringing to the world.

- Xerox Corporation released “A Metamorphosis of Creative Copying” in 1964, which seems to function as both promotion for Xerox and a weird gift to give to your kids to color in.

- In 2014, a short zine called The Tao of Bitcoin was released, telling people the dream of $10,000 bitcoin would be real.

- The 1888 chapbook Goody Two-Shoes has lovely illustrations, and a fine short story.

- Working with a lovely couple who brought in a 1942 black-owned-businesses directory, I scanned the pages by hand and put them up into this item.

- Inside that directory was an ad for a school of whistling that said it taught using the methods of Agnes Woodward, and a quick scan of the Archive’s stacks showed that we had an entire copy of her book Whistling as an Art!

- The medical treatise Sleep and Its Derangements, from 1869, is William A. Hammond, MD’s overview of sleep, and what can go wrong. Scanned from the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, it’s one of many thousands of books we’ve scanned with partners.

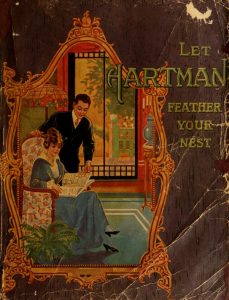

- Let Hartman Feather Your Nest could be described as “A furniture catalog” in the same way the Sistine Chapel could be described as “a place of worship”. The catalog is a thundering, fist-pounding declaration of the superiority of the Hartman enterprise and the quality and breadth of furniture and service that will arrive at your door and be backed up to the far reaches of time.

Magazines

- Photoplay considered itself the magazine for the motion picture industry in the first part of the 20th century, and this multi-volume compilation of photos, articles and advertisements is a truly lovely overview.

- There’s over 140 issues of the classic Maximum RockNRoll zine, truly the king of music zines for a very long time. On its newsprint pages are howls and screeches of all manner of punk, rock and the needs of musicians.

- A magazine created by the Walt Disney Company to trumpet various parts of Disneyland and its attractions was called Vacationland, and this Fall 1965 issue covers all sorts of stuff about the park’s first decade.

Movies

- Rescued from a warehouse years ago, a collection of Hollywood movie “B-Roll”, unused secondary scenes often filmed by different crew, has been digitized. My personal favorite is [Western Film Scenes], which is circa 1950s footage of a Western Town, all of it utterly fake but feeling weirdly real, to be used in a western. Don’t miss everyone standing around looking right at you and looking like they agree quite energetically with you!

- No compilation could be complete without the legendary Duck and Cover, a cartoon/PSA that explained the simple ways to avoid injury in a nuclear blast. Just lie down! It’ll be fine. Please note: This Probably Won’t Work. But the song is very catchy.

- The very weird Electric Film Format Acid Test from 1990 has a semi-interested model holding up a color bar plate in a wide, wide variety of film and video formats. Filmed just a few blocks away from the Internet Archive’s current headquarters.

- I snuck in a 1992 interview with the Archive’s founder, Brewster Kahle, back when he was 33 and working at WAIS, a company or two before the Archive and where he is asked about his thoughts on information and gathering of data. It’s quite interesting to hear the consistency of thought.

- The Office of War Information worked with Disney to create “Dental Health“, a film to show to troops about proper dental care. It’s a combination of straightforward animation and industrial film-making worth enjoying.

Audio

- We have a collection of hours of the radio show The Shadow from 1938-1939, starring Orson Welles at 23, at the height of his performance powers, playing the dual main role.

- For Christmas Eve, we pointed to “Christmas Chopsticks”, a 1953 78rpm record of “Twas the Night Before Christmas” performed to the tune of the classic piano piece “Chopsticks”; one of tens of thousands of 78rpm records the Archive has been adding this year.

- On Christmas, a user of the Archive uploaded two obscure albums he’d purchased on eBay – remnants of the S. S. Kresge Company, which became K-Mart, and which were played over the PA system for shoppers. He got his hands on Albums #261 and #294.

- Earlier in the month before the user uploaded those Christmas albums, I linked to a different holiday collection of K-Mart items, a 1974 Reel-to-Reel that started with a K-Mart jingle and went full holiday from there.

- Before he was a (retired) talk show host, and before he was a stand-up comedian, David Letterman worked and trained in radio. Happily, we have recordings of Dave Letterman, DJ, from when he was 22, at Ball State University.

- Ron “Boogiemonster” Gerber has been hosting his weekly pop music recycling radio show, “Crap from the Past”, for over 25 years, and he’s been uploading and cataloging his show to the Archive for well over 10 of those years, including all the way back to the beginning of his show. The full Crap From The Past archive is up and is hundreds of hours of fun.

- The truly weird “Conquer the Video Craze” is a 1982 record album with straightforward descriptions of how to beat games like Centipede, Defender, Stargate, Dig Dug, and more. This album has been sampled from by multiple DJs to bring that extra spice to a track.

- Over 3,000 shows at the DNA Lounge are at the archive, including “Bootie: Gamer Night“, which combines mash-up tracks and video games. Bootie has been playing at DNA Lounge for years, and puts the audio from one song with the singing from another, and… it’s quite addicting, like games. This night was for the nearby Game Developers’ Conference being held the same week.

Software

- In 2011, as part of a “retrocomputing” competition, we saw the release of “Paku-Paku”, a pac-clone program which ran in an obscure early PC-Compatible graphics mode that was very colorful and very small (160×100) and was built perfectly for it. You can play the game in your browser by clicking here.

- Psion Chess is a game for the Macintosh that can play both you and itself with pretty high levels of skill and really sharp and crisp black and white graphics. It makes a really great screensaver in self-playing mode.

People often overuse a phrase like “Barely scratched the surface”, but I assure you there are millions of amazing items in the archive, and it’s been a pleasure to bring some to light. While the 30 Days of Stuff was a fun way to stretch out a month of fundraising with stuff to see every day, we’re here 24/7 to bring you all these items, and welcome you finding jewels, gems and clunkers throughout our hard drives whenever you want.

Thanks for another year!

Mnemosyne was the Greek muse who personified memory. She was a Titaness who was the daughter of Uranus (who represented “Sky”), the son and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth. When you break it down, Mnemosyne had a deeply complicated life, and ended up birthing the other muses with her nephew, Zeus. Ancient Greek myth was quite an incestuous place, and every deity had complicated and deeply interwoven histories that added layers and layers of what we would now call “intertextuality.” Look at it this way: a Titaness, Mnemosyne, gave birth to Urania (Muse of Astronomy), Polyhymnia (Muse of hymns,) Melpomene (Muse of tragedy,) Erato (Muse of lyric poetry,) Clio (Muse of history,) Calliope (Muse of epic poetry,) Terpsichore (Muse of dance,) and Euterpe (Muse of music). It’s complicated. Mnemosyne also presided over her own pool in Hades as a counterpoint to the river Lethe, where the dead went to drink to forget their previous life. If you wanted to remember things, you went to Mnemosyne’s pool instead. You had to be clever enough to find it. Otherwise, you’d end up crossing the river under the control of spirits guided by the “helmsman” whose title translates from the Greek term “kybernētēs” across the mythical river into the land of the dead aka Hades. What’s amazing about the wildly “recombinant” logic of this cast of characters is that somehow it became the foundation of our modern methods for naming almost every aspect of digital media — including the term “media.” Media, like the term data is a plural form of a word “appropriated” directly from Latin. But the eerie resonance it has with our era comes into play when we think of the ways “the archive” acts as a downright uncanny reflection site of language and its collision between code and culture.

Mnemosyne was the Greek muse who personified memory. She was a Titaness who was the daughter of Uranus (who represented “Sky”), the son and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth. When you break it down, Mnemosyne had a deeply complicated life, and ended up birthing the other muses with her nephew, Zeus. Ancient Greek myth was quite an incestuous place, and every deity had complicated and deeply interwoven histories that added layers and layers of what we would now call “intertextuality.” Look at it this way: a Titaness, Mnemosyne, gave birth to Urania (Muse of Astronomy), Polyhymnia (Muse of hymns,) Melpomene (Muse of tragedy,) Erato (Muse of lyric poetry,) Clio (Muse of history,) Calliope (Muse of epic poetry,) Terpsichore (Muse of dance,) and Euterpe (Muse of music). It’s complicated. Mnemosyne also presided over her own pool in Hades as a counterpoint to the river Lethe, where the dead went to drink to forget their previous life. If you wanted to remember things, you went to Mnemosyne’s pool instead. You had to be clever enough to find it. Otherwise, you’d end up crossing the river under the control of spirits guided by the “helmsman” whose title translates from the Greek term “kybernētēs” across the mythical river into the land of the dead aka Hades. What’s amazing about the wildly “recombinant” logic of this cast of characters is that somehow it became the foundation of our modern methods for naming almost every aspect of digital media — including the term “media.” Media, like the term data is a plural form of a word “appropriated” directly from Latin. But the eerie resonance it has with our era comes into play when we think of the ways “the archive” acts as a downright uncanny reflection site of language and its collision between code and culture. Until the internet, the term cyber was usually used to measure words about governance and then later evolved to how we look at computers, computer networks, and now things like augmented reality and virtual reality. The term traces back to the word cybernetics, which was popularized by the renowned mathematician Norbert Wiener, founder of Information theory, at MIT. There’s a strange emergent logic that connects the dots here: permutation, wordplay, and above all, the use of borrowed motifs and ahistorical connections between utterly unassociated material. I guess William S. Burroughs was right: the world has become a mega-Cybertron, a place where everything is mixed, cut and paste style, to make new meanings from old. With people like Norbert Wiener, cybernetics usually refers to the study of mechanical and electronic systems designed at heart, to replace human systems. The term “cyberspace” was coined by William Gibson, to reflect the etherealized world of his 1982 classic, Burning Chrome. He used it again as a reference point for Neuromancer, his groundbreaking novel. A great, oft-cited passage gives you a sense how resonant it is with our current time:

Until the internet, the term cyber was usually used to measure words about governance and then later evolved to how we look at computers, computer networks, and now things like augmented reality and virtual reality. The term traces back to the word cybernetics, which was popularized by the renowned mathematician Norbert Wiener, founder of Information theory, at MIT. There’s a strange emergent logic that connects the dots here: permutation, wordplay, and above all, the use of borrowed motifs and ahistorical connections between utterly unassociated material. I guess William S. Burroughs was right: the world has become a mega-Cybertron, a place where everything is mixed, cut and paste style, to make new meanings from old. With people like Norbert Wiener, cybernetics usually refers to the study of mechanical and electronic systems designed at heart, to replace human systems. The term “cyberspace” was coined by William Gibson, to reflect the etherealized world of his 1982 classic, Burning Chrome. He used it again as a reference point for Neuromancer, his groundbreaking novel. A great, oft-cited passage gives you a sense how resonant it is with our current time:

J Spooky’s work ranges from creating the first DJ app to producing an impactful DVD anthology about the “Pioneers of African American Cinema.” According to a

J Spooky’s work ranges from creating the first DJ app to producing an impactful DVD anthology about the “Pioneers of African American Cinema.” According to a

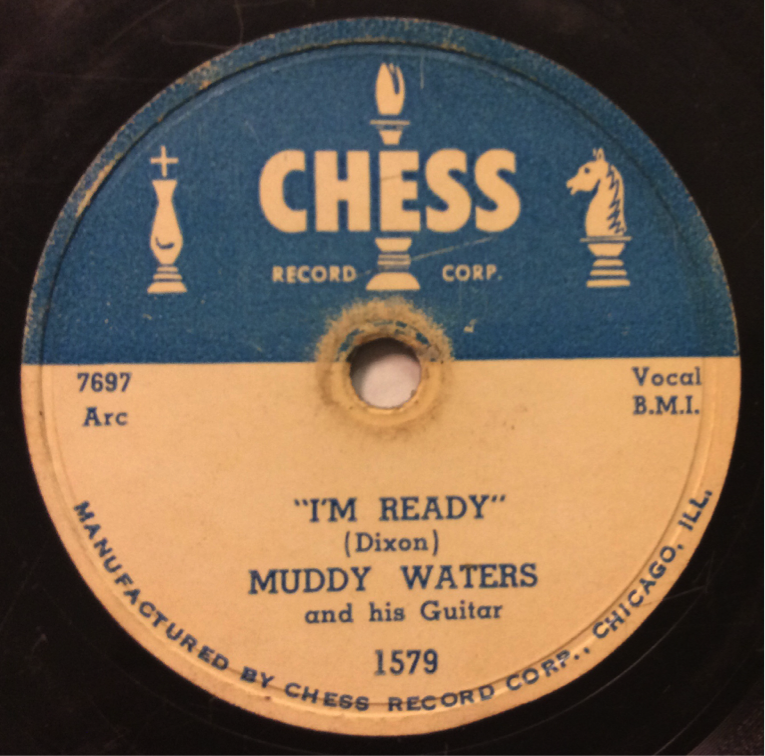

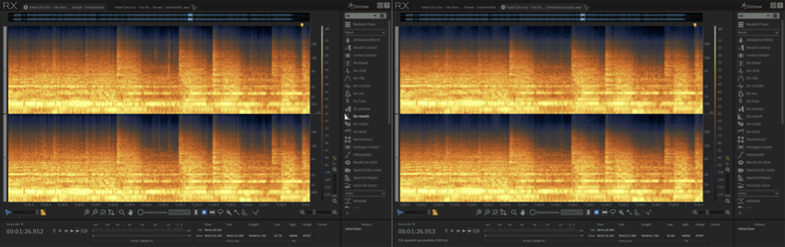

The trick to repacking in a timely fashion is to not look at the records. It’s a trick that is never performed successfully. Handling fragile 78s requires grabbing one or just a few at a time. So we’re endlessly reading the labels, sleeving and resleeving, all the time checking for rarities, breakage and dirt.

The trick to repacking in a timely fashion is to not look at the records. It’s a trick that is never performed successfully. Handling fragile 78s requires grabbing one or just a few at a time. So we’re endlessly reading the labels, sleeving and resleeving, all the time checking for rarities, breakage and dirt.