By Jessica Thompson, Coast Mastering

The Great 78 Project

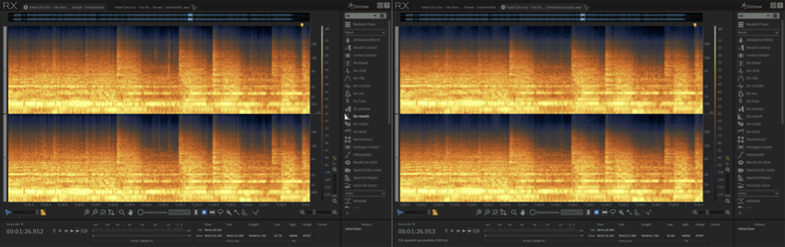

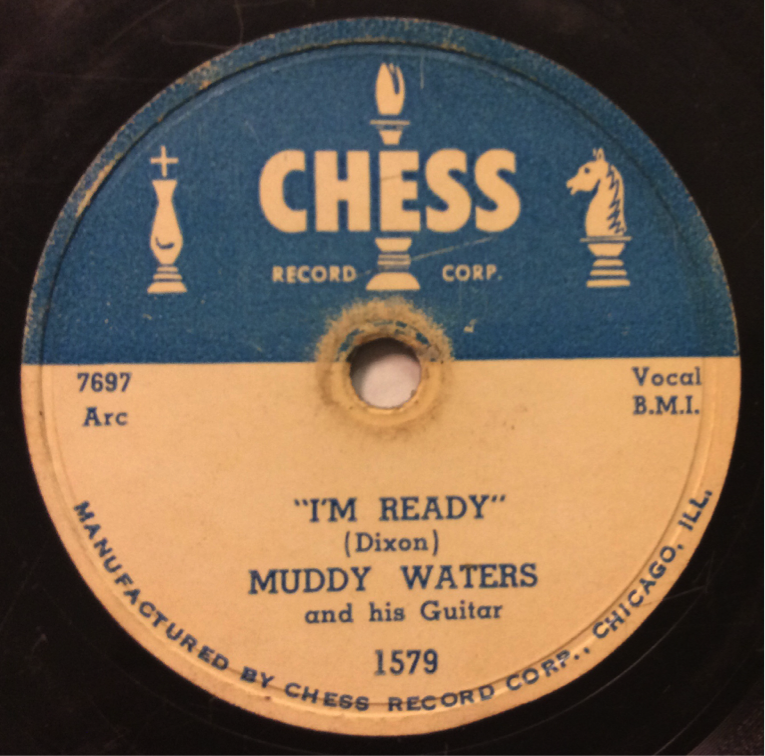

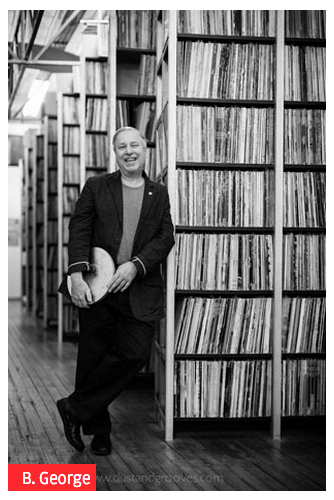

A few times a year, I join B. George in the Internet Archives’ warehouses to help sort and pack 78rpm discs to ship to George Blood L.P. for digitization. As a music fan and a professional mastering and restoration engineer, I get a thrill from handling the heavy, grooved discs, admiring the fonts and graphic designs on the labels, and chuckling at amusing song titles. Now digitized, these recordings offer a wealth of musicological, discographic and technical information, documenting and contextualizing music and recording history in the first half of the 20th century.

The sheer scale of this digitization project is unprecedented. At over 15,000 recordings and counting, the value strictly in terms of preservation is clear, especially given the Internet Archive’s focus on digitizing music less commonly available to researchers. Music fans can take a deep dive into early blues, Hawaiian, hillbilly, comedy and bluegrass. I even found several early Novachord synthesizer recordings from 1941.

As a researcher and audio restoration engineer, the real goldmine is in the aggregation of discographic and technical metadata accompanying these recordings. Historians can search for and cross reference recordings based on label, artist, song title, year of release, personnel, genre, and, importantly, collection. (The Internet Archive documents the provenance of the 78rpm discs so that donated collections remain digitally intact and maintain their contextual significance.) General users can submit reviews with notes to amend or add to metadata, and the content of those reviews is searchable, so metadata collection is active. No doubt it will continue to improve as dedicated and educated users fill in the blanks.

Access to the technical metadata offers a valuable teaching tool to those of us who practice audio preservation. For audio professionals new to 78s and curious about how much difference a few tenths of a millimeter of stylus can make, the Internet Archive offers 15,000+ examples of this. Play through the different styli options, and it quickly becomes apparent that particular labels, years and even discs do respond better to specific styli sizes and shapes. This is something audio preservationists are taught, but rarely are we presented with comprehensive audio examples. To be able to listen to and analyze the sonic and technical differences in these versions marries the hard science with the aesthetic.

Playback speeds were not standardized until the late 1920s or early 1930s, and most discs were originally cut at speeds ranging from 76-80rpm (and some well beyond). The discs in the George Blood Collection were all digitized at a playback speed of 78rpm. Preservationists and collectors debate extensively about the “correct” speed at which discs ought to be played back, and whether one ought to pitch discs individually. However, performance, recording and manufacturing practices varied so widely that even if a base speed could generally be agreed upon, there will always be exceptions. (For more on this, please check out George Blood’s forthcoming paper Stylus Size And Speed Selection In Pre-1923 Acoustic Recordings in Sustainable audiovisual collections through collaboration: Proceedings of the 2016 Joint Technical Symposium. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.)

Every step of making a recording involves so many aesthetic decisions – choices of instrumentation, methods of sound amplification, microphone placement, the materials used in the disc itself, deliberate pitching of the instruments and slowing or speeding of the recording – that playback speed simply become one of many aesthetic choices in the chain. As preservationists, we are preserving the disc as an historic record, not attempting to restore or recreate a performance. (Furthermore, speed correction is possible in the digital realm, should anyone want to modify these digital files for their own personal enjoyment).

How do they sound? Each 78rpm disc has an inherent noise fingerprint based on the frequency and dynamic range the format can replicate (limited, compared to contemporary digital playback formats) and the addition of surface noise from dust, dirt and stylus wear in the grooves. As expected, the sound quality in this collection varies. Some of these discs were professionally recorded, minimally played, stored well, and play back with a tolerable, even ignorable level of surface noise relative to the musical content. Others were recorded under less professional circumstances, and/or were much loved, frequently played, stored without sleeves in basements and attics, and therefore suffer from significant surface noise that can interfere with enjoyment (and study) of the music.

Yet, a compelling recording can cut through noise. Take this 1944 recording of Josh White performing St. James Infirmary, Asch 358-2A. This side has been released commercially several times, so if you look it up on a streaming service like Spotify, you can listen to different versions sourced from the same recording (though almost certainly not from the same 78rpm disc). They play at different speeds, some barely perceptibly faster or slower but at least one nearly a half-step faster than the preservation copy digitized by George Blood L.P. They also have a range of noise reduction and remastering aesthetics, some subtle and some downright ugly and riddled with digital artifacts. The version on the Internet Archive offers a benchmark. This is what the recording sounded like on the original 78rpm disc. Listen to the bend in the opening guitar notes. That technique cuts through the surface noise and should be preserved and highlighted in any restored version (which is another way of saying that any noise reduction should absolutely not interfere with the attack and decay of those luscious guitar notes).

McGill University professor of Culture and Technology Jonathan Sterne wrote a book – The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction – that is worth reading for anyone interested in a cultural history of early recording formats, including 78s. As Sterne says, sound fidelity is “ultimately about deciding the values of competing and contending sounds.” So, in listening to digital versions of 78s on the Internet Archive, music fans, researchers, and audio professionals alike engage in a process of renegotiating concepts of acceptable thresholds of noise and what that noise communicates about the circumstances of the recording and its life on a physical disc.

Fortunately, our brains are very good at calibrating to accept different ratios of signal to noise, and, I found, the more I listened to 78rpm recordings on the Internet Archive, the less I was bothered by the inherent noise. Those of us who grew up on CDs or digitally recorded and distributed music are not used to the intrusions of surface noise. However, when listening to historic recordings, we are able to adjust our expectations and process a level of noise that would be ridiculous in contemporary music formats. (Imagine this week’s Billboard Top 100 chart topper, Bruno Mars’s “That’s What I Like,” with the high and low end rolled off, covered in a sheen of crackles and pops). The fact that these 78rpm recordings sound, to us, like they were made in the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s lets them get away with a different scale of fidelity. The very nature of their historicity gets them off the hook.

In analog form, crackles and pops can be mesmerizing, almost like the sound of a crackling fire. However, once digitized, those previously random pops become fixed in time. What may have been enjoyable in analog form becomes a permanent annoyance in digital form. The threshold of acceptable noise levels moves again.

This means that noise associated with recording carriers such as 78rpm discs is almost always preferably to noises introduced in the digital realm through the process of attempted noise reduction. Sound restorationists understand that their job is to follow a sonic Hippocratic oath: do no harm. Though noise reduction tools are widely available, they range in quality (and accordingly in cost), and are merely tools to be used with a light or heavy touch, by experienced or amateur restorationists.

The question of whether noise reduction of the Internet Archive’s 78rpm recordings could be partially automated makes my heart palpitate. Though I know from experience that, for example, auto-declickers exist that could theoretically remove a layer of noise from these recordings with minimal interference with the musical signal, I don’t believe the results would be uniformly satisfactory. It is so easy to destroy the aura of a recording with overzealous, heavy-handed, cheap, or simply unnecessary noise reduction. Even a gentle touch of an auto-declicker or de-crackler will have widely varying results on different recordings.

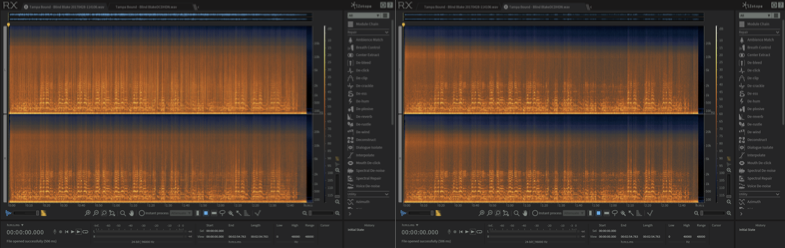

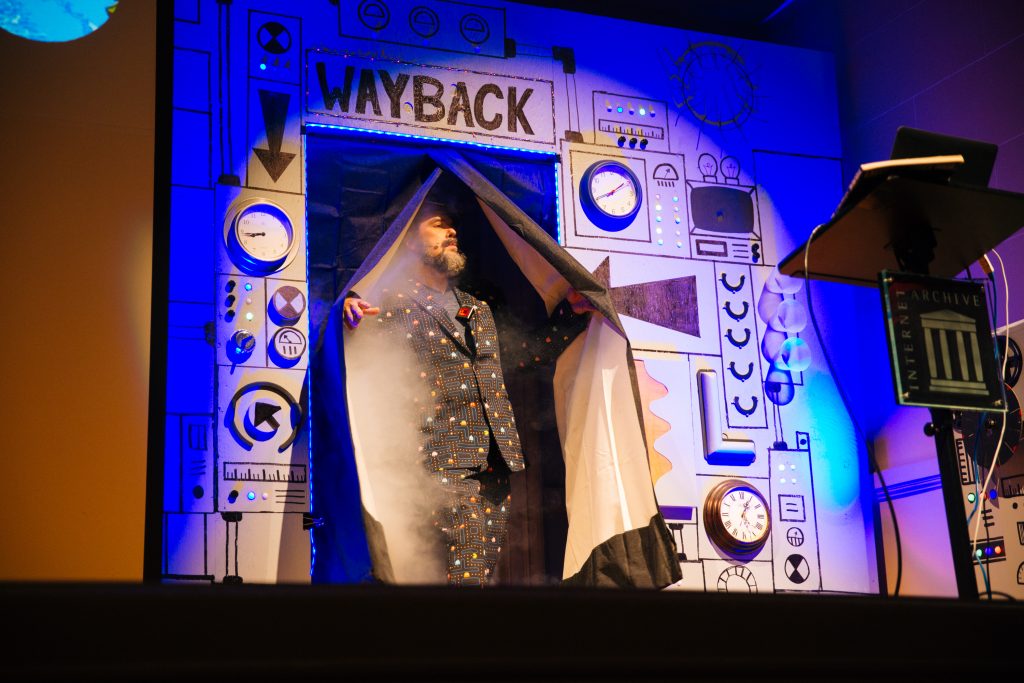

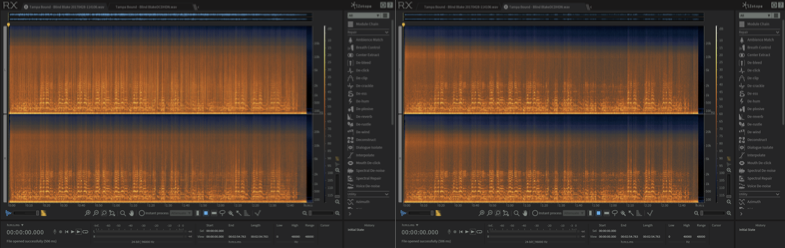

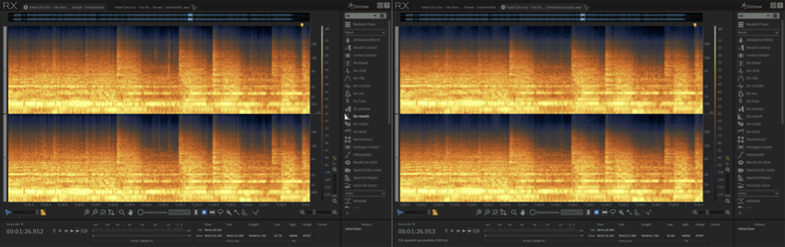

I tried this with a sampling of selections from the /georgeblood/ collection. I chose eleven songs from different genres and years and ran two different, high quality auto-declickers (the iZotope RX6 Advanced multiband declicker and CEDAR Audio’s declick) on the 24bit FLAC files. The results were uneven. Some of the objectively noisier songs, such as Blind Blake’s Tampa Bound, Paramount 12442-B, benefited from having the most egregious surface noises gently scrubbed.

Tampa Bound Flat Transfer vs Tampa Bound Declicked, Dehissed and Denoised

that’s a lot of noise!

However, a song with a strong musical presence and mild surface noise such as Trio Schmeed’s Yodel Cha Cha, ABC-Paramount 9660, actually suffered more from light auto-declicking because the content of the horns and percussive elements registered to the auto-delicker as aberrations from the meat of the signal and were dulled. A pop presents as an aberration across all frequencies. Mapped visually across frequency, time and intensity, it looks like a spike cutting through the waveform. A snare hit looks similar and is therefore likely to be misinterpreted by an auto-declicker unless the threshold at which the declicker deploys is set very carefully. This difference is why good restorationists earn their pay.

Yodel Cha Cha flat transfer and denoised. Notice the “clicks and pops” have been scrubbed,

but so has wanted high end content in the music.

I am approaching this collection as a listener and music fan, as a researcher, and as an audio professional, three very different modes of listening and interacting with music. In all cases, the Internet Archive 78rpm collection offers massive amounts of music and data to be explored, discovered, enjoyed, studied and utilized. Whether you want to listen to early Bill Monroe tunes, crackles, pops and all, or explore hundreds of recordings of pre-war polkas, or analyze the effects of stylus size on 1930s Victor discs, the Internet Archive provides the raw materials in digital form and, not to be underestimated, preserves the original discs too.

By working together, libraries who are digitizing their collections can minimize duplication of effort in order to save time and money to preserve other things. This month we made progress with 78rpm record collections.

By working together, libraries who are digitizing their collections can minimize duplication of effort in order to save time and money to preserve other things. This month we made progress with 78rpm record collections.

this tour through the 20th century, the Time Machine was set to 1997. Mark Graham, Director of the

this tour through the 20th century, the Time Machine was set to 1997. Mark Graham, Director of the

The trick to repacking in a timely fashion is to not look at the records. It’s a trick that is never performed successfully. Handling fragile 78s requires grabbing one or just a few at a time. So we’re endlessly reading the labels, sleeving and resleeving, all the time checking for rarities, breakage and dirt.

The trick to repacking in a timely fashion is to not look at the records. It’s a trick that is never performed successfully. Handling fragile 78s requires grabbing one or just a few at a time. So we’re endlessly reading the labels, sleeving and resleeving, all the time checking for rarities, breakage and dirt.

When the personal record collection of music producer Bob George hit 47,000 discs, he knew something had to be done. “I wanted to give them away, but they were mostly punk, reggae and hip-hop,” he recalled, “and no established library or archive was interested.” The only thing to do, it would seem, was to turn his collection into a non-profit archive in New York called the

When the personal record collection of music producer Bob George hit 47,000 discs, he knew something had to be done. “I wanted to give them away, but they were mostly punk, reggae and hip-hop,” he recalled, “and no established library or archive was interested.” The only thing to do, it would seem, was to turn his collection into a non-profit archive in New York called the  Powered by teams of volunteers, the two archives are partnering to digitize CDs and LPs and then use audio fingerprinting to match tracks with metadata from catalogs and other services. Using Internet Archive scanners, the ARC is digitizing its books and photographs at its New York facility. When complete, this music library will be a rich resource for historians, musicologists and the general public.

Powered by teams of volunteers, the two archives are partnering to digitize CDs and LPs and then use audio fingerprinting to match tracks with metadata from catalogs and other services. Using Internet Archive scanners, the ARC is digitizing its books and photographs at its New York facility. When complete, this music library will be a rich resource for historians, musicologists and the general public.

Since 1985, George, the ARC’s co-founder and director, has run the organization in Tribeca, New York City, supported by friends in the music industry including Paul Simon, David Bowie and Nile Rodgers. The Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards endows a collection of blues and R&B recordings there. Filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme stop by when trying to track down hard-to-find songs. Yet for most of its almost three decades, the ARC has been a decidedly “analog” experience: records, CDs and cassette tapes line its walls; to experience a song you usually have to drop a needle into a pristine vinyl groove. The collaboration with the web-based Internet Archive represents a new direction. “We feel that our primary mission, to collect and preserve this material, is near completion,” said Bob George. “Now we are seeking ways to allow greater access to this incredible collection.”

Since 1985, George, the ARC’s co-founder and director, has run the organization in Tribeca, New York City, supported by friends in the music industry including Paul Simon, David Bowie and Nile Rodgers. The Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards endows a collection of blues and R&B recordings there. Filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme stop by when trying to track down hard-to-find songs. Yet for most of its almost three decades, the ARC has been a decidedly “analog” experience: records, CDs and cassette tapes line its walls; to experience a song you usually have to drop a needle into a pristine vinyl groove. The collaboration with the web-based Internet Archive represents a new direction. “We feel that our primary mission, to collect and preserve this material, is near completion,” said Bob George. “Now we are seeking ways to allow greater access to this incredible collection.”