Everyone has a different idea of what they’d do with a time machine. Mine’s pretty simple: Head back to 2012, find myself working on a side project to film a documentary, and grab my younger self by the lapels and shout, “A 1099 IS NOT A REIMBURSEMENT! GET AN ACCOUNTANT!” before whatever energy sending me into the past gave out.

That simple mistake on my part had truly stunning financial consequences. When the tax bills and penalties started hitting my mailbox around 2014, it became a mass of stress. The IRS is undefeated in the award for Most Intense Collection Letters, and they were coming on a regular basis, even as I started directing more and more of my paycheck towards paying the debt.

A few friends generously sent me money to help beat back the interest and costs, but the combination of this and other debts had me backed into a corner, so I decided on a simple plan: Run a Patreon campaign where I told stories and opinions in short episodes, which were then supported by the audience, with all the proceeds going into debt repayment. The resulting podcast, Jason Scott Talks His Way Out of It, helped dig me out of that hole.

But it had an interesting side effect – coming up with new topics of discussion and consideration, once a week, meant that I had to mine deeper and deeper into my own outlook and relevant stories. After the first fifty episodes, I turned further inward. After one hundred, it became equal parts emotional and technical. And as I’m heading towards three hundred episodes, I’m surprised I have anything left to say at all. But I apparently do, and having now been doing this podcast weekly for six years, its episodes span a truly panoramic spectrum of topics.

(This is what a standing recording booth looks like – putting your head in an Audio Mailbox to maintain quiet background noise while speaking. It gets very hot in there.)

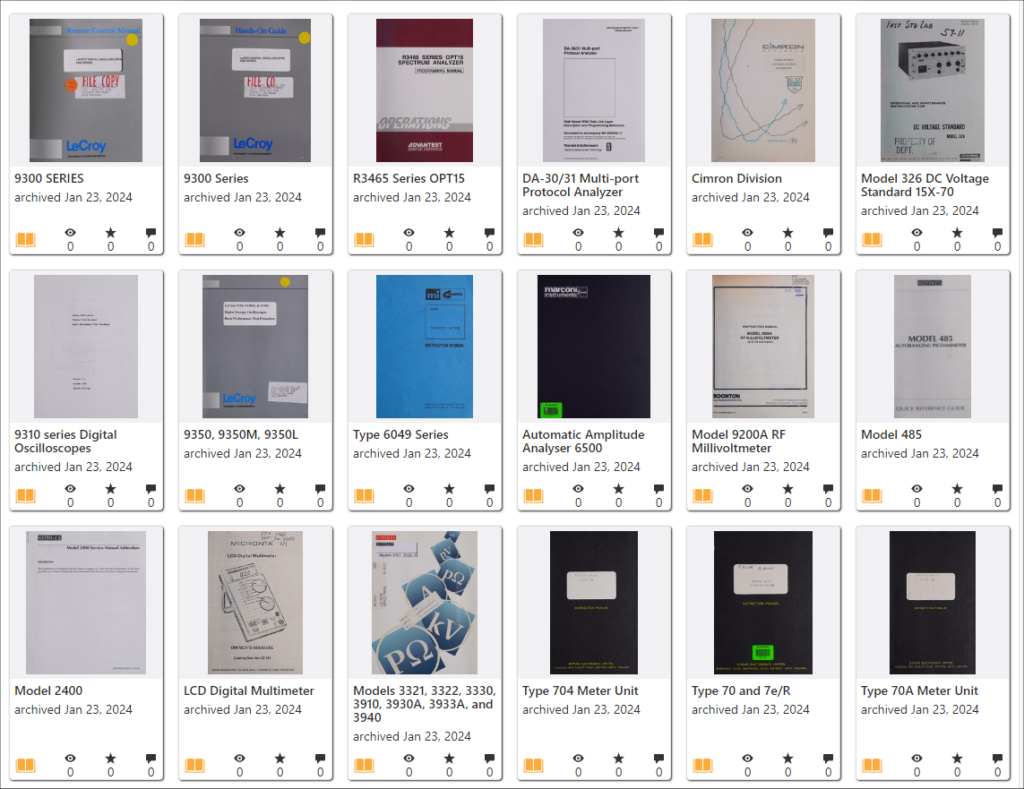

The Patreon gave patrons early access to the episodes, but the episodes are all open and uploaded some months later to the general world, including this collection at Internet Archive. Download, listen, remix, whatever you’d like – you have my complete permission and blessing.

Episodes have been uploaded to the Internet Archive since 2019, but in 2022, an opportunity try out new technology came up – the Whisper project, open sourced and instantly downloadable, could be implemented for transcription, either as part of video or just a basic audio file. And thanks to the project, I had many audio files, and began experimenting with using Whisper against them.

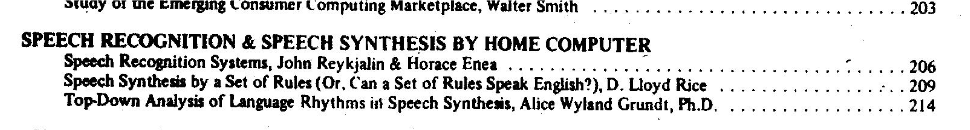

Speech recognition, the process of turning spoken words in a microphone or pre-recorded audio files into written words or issued commands, has been around a very long time – decades and decades. The Internet Archive is excellent for doing a dive into historical citations; a fast “text contents” search found these points of discussion in a 1979 issue of the Silicon Gulch Gazette newsletter:

What has changed is the combination of much faster computers, much more analysis of speech, and advances in cross-referencing the resulting training to make chips and, in this case, a program that is using other disciplines within computer science to pattern-match audio, to the point of adding capitalization and punctuation from the implications in the words. Turning this against my growing collection of podcasts, it wasn’t long before I’d say what has continued to be a theme: when it works, it’s shockingly good, and when it doesn’t, it’s shockingly bad.

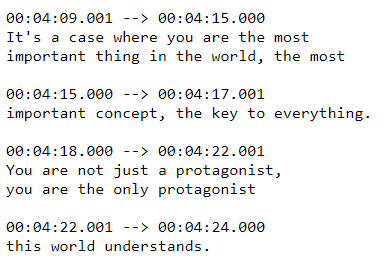

As an experiment and exploration, it was very useful to let the program run, shoot out a block of text, and generate the resulting timing blocks for the purposes of subtitles or transcription:

…but it would have been foolhardy to 100% walk away and let it do transcription without a second human-driven scan through the results to find mistakes. I’ve been that human, and I’ve seen things.

I’ve seen the resulting transcriptions do great jobs with proper name capitalization, odd and challenging punctuation, and paragraph breaks. I’ve also seen it knock itself silly on my New York accent and non-obscure phrasing, and definitely making a poor guess on my made-up word “Cowicature”. The algorithm works great, except when it doesn’t.

And here we get to a turn of phrase I’ve come to adapt, which is an alternate term for AI: “Algorithmic Intensity”. The human need to give life and will to machinery is a very long-lived one; but most who look at the code behind this mechanism would agree – it’s just code. The only difference is that the amount of computing power and data to derive the outcome dwarfs numbers considered unattainable a decade or two ago.

And the speed can’t be beat – 5 years of weekly podcasts took roughly 4 hours to completely transcribe by Whisper, and that amount of time was simply because it was set as a lower-priority action in the queueing system. Knowing how long the total time for all the uploaded episodes of my podcast are sitting in that collection is a little involved, but my back of napkin estimation is it’s two and a half solid days of me talking about technology and emotion, ranging subjects from programming and compilers to summer camp and family. I can assure you – I was not going to transcribe these podcasts anytime soon, and I was not going to ask someone to do it. While I’m proud of my work, I’m in no position to be able to record four podcasts in a month and create paragraphs of text from them.

Or, for that matter, descriptive summaries.

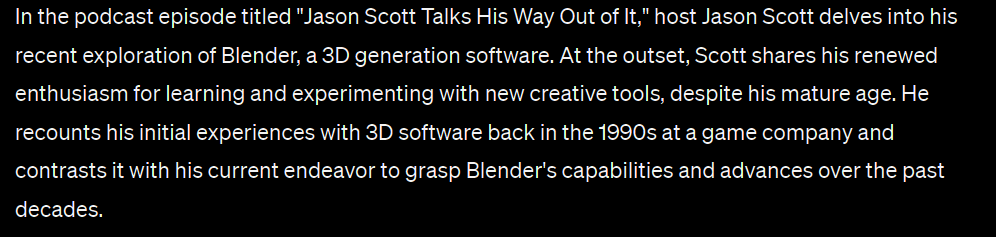

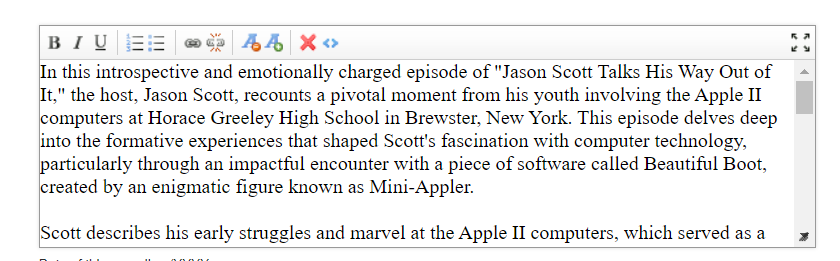

Which brings me to the latest, continual tinkering with the tools and environment available to analyze materials with algorithms. I began asking a large language model to look at the generated transcriptions and create a summary of a given podcast episode.

Two-plus years into generalized algorithmic intensity access, it’s still very much a lumpy and oddly spell-casting endeavor. Instead of asking it to “summarize this transcription”, my request reads like a headmaster at a school or a Dungeons and Dragons game text:

You read transcripts of a podcast and carefully write out descriptions, in the form of narrative paragraphs, to accurately describe the content of the podcast. Longer and more complete descriptions are better, and encouraged. You describe the main subjects, conclusions by the participants, and provide helpful context for the subjects. The podcast you listen to is:

…followed by the transcription of the podcast, time-codes and all.

A matrix of calculation, fast beyond my reckoning but not less mysterious-and-not-mysterious as CPUs and networking itself, begins analyzing the language in the transcriptions, cross-connecting ideas mentioned, occasionally volunteering more information based on matches to terms, and within a few minutes, language comes out.

…in this language, it’s easy to find places where there’s an algorithm in the mix, a machine putting out syllables and phrases based on what I said. Like a kaleidoscope or a magnifying glass, there are occasional strange distortions and what approaches funhouse-mirror reflections of what I put in.

And oddly enough, it brings up memories.

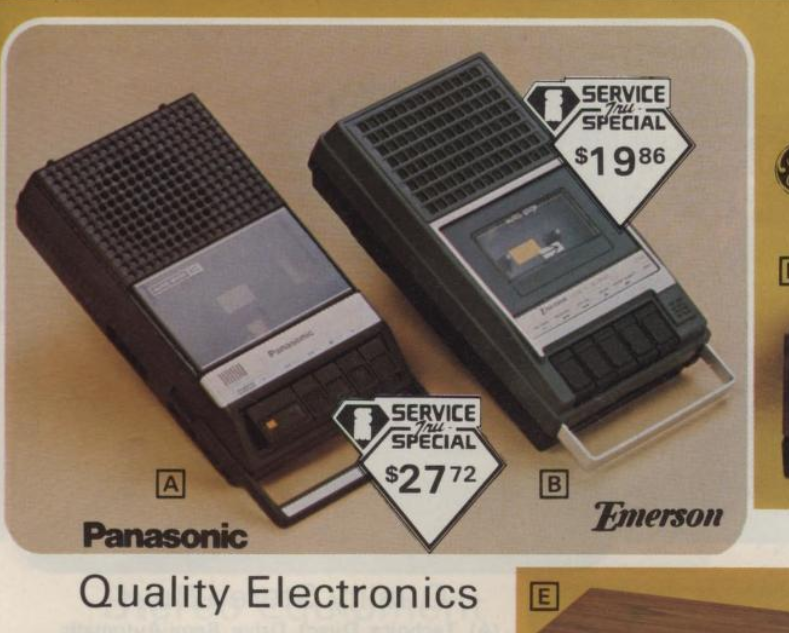

It reminds me of being in my first neighborhood and all the kids circled around a fun and weird toy, a tape recorder, where you pressed two buttons and the … cassette, it was called? Would turn slowly and you would shout whatever came to the top of your head, press STOP, and then rewind and hear your own voice. It was distorted and weird, but it was my own voice, and I’d not heard it before from outside my own head. The world shifted, a little bit.

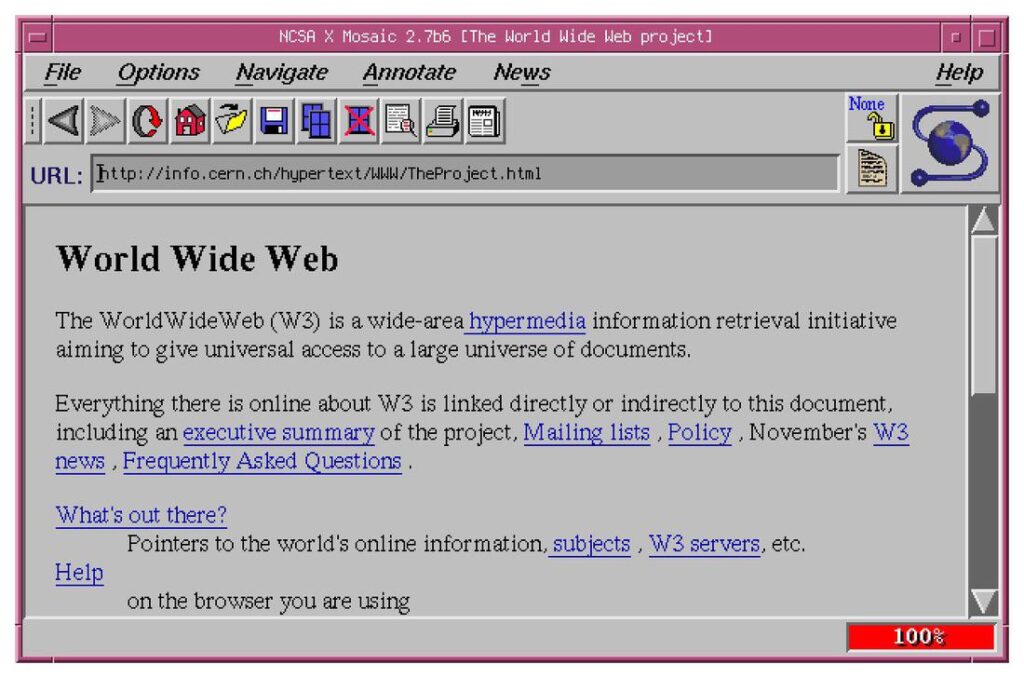

It reminds me of being in a computer lab at MIT in my twenties, playing games on a lunch break during a temp job I had on campus, and finding out that if I went to this obscure IP number and downloaded this very large binary file and ran it, this gargantuan program would pop up and begin asking me what “address” to go to, and if I knew some of the addresses, they would turn into full-color, fully-laid out, beautiful print-like presentations along a grey background. And, to my utter disbelief, looking at a menu option called “view source” would let me see the bizarre “code” behind these lovely looking pages. It was called Hypertext Mark-Up Language, HTML, and messing with that odd and ever-changing set of written directives inside textfiles would be a significant part of my next quarter century.

There have been all these times the times that computers (on my desk or lab or out in some nebulous “net” that girdled the Earth) provided me with a new set of buttons and knobs to press. To play around. To see what hums and clicks, and to do my best to understand what is happening underneath. In many ways, these computers have done very well by me; and they have also brought stress, sleepness nights and confusion; even anger.

Put another way, these newest concepts and tools, these Intense Algorithms, sweeping the news and the discussion around virtual watercoolers, are the latest in a long line of topics about what computers will bring to human lives. It’s a deep and varied discussion and it deserves consideration and time, and respect of the opinions of others.

And while (hopefully) the world processes this newest use of computers, we’ll see where, if anywhere, they’ll help with the mass of information and digital materials that sites like the Internet Archive provide.

Asking an LLM to look at the full text of a nearly 200-page book about the raising of ducks, such as the legendary DUCKS; AND HOW TO MAKE THEM PAY (1924), provides a paradise of questions you can ask the book as if it was able to answer in full sentences:

Q: How, exactly, do you make ducks pay?

A: The book “Ducks: and how to make them pay” by William Cook outlines various methods for making duck farming profitable. It covers the selection of suitable duck breeds, breeding techniques, and the proper management of feeding and housing. Additionally, it provides insights into marketing strategies for selling ducks and their eggs. The goal is to guide readers on how to efficiently manage duck farms to maximize income from their operations.

Q: What is, in your opinion, the best duck?

A: Choosing the “best” duck depends on what you’re looking for! For farming purposes, the Pekin duck is often considered ideal because it grows quickly and has a high yield of meat. If egg production is your priority, the Khaki Campbell duck is highly recommended, as it is one of the most prolific egg layers. For those interested in ornamental ducks, breeds like the Mandarin or Wood Ducks are known for their striking appearances. Each breed has its own advantages depending on your goals and the specific requirements of your duck farming or hobbyist endeavors.

(…as an aside, the book has one of the best bookplates inside the front cover, one which only a human being would truly apprecate.)

And that’s how I see the near future with this newest use of computers – an implementation of these tools to make materials easier to find, to summarize and help point researchers and students, and allowing new ways to work with a staggering amount of information in the online stacks. Hiding from it won’t be a solution; but asking hard questions of it might be.

Meanwhile, six years of my spoken-word memories of the ways computers have affected my life are sitting in a collection, open to all and welcome for anyone to use to tinker with. Have a great time.