When we started archiving television in 2000, people shrugged and asked, “Why? Isn’t it all junk anyway?” As the saying goes, one person’s junk is another person’s gold. From 2010-18, scholars, pundits and above all, reporters, have spun journalistic gold from the data captured in our 1.5 million hours of television news recordings. Our work has been fueled by visionary funders(1) who saw the potential impact of turning television – from news reports to political ads – into data that can be analyzed at scale. Now the Internet Archive is taking its Television Archive in new directions. In 2018 our goals for television will be: better curation in what we collect; broader collection across the globe; and working with computer scientists interested in exploring our huge data sets. Simply put, our mission is to build and preserve comprehensive collections of the world’s most important television programming and make them as accessible as possible to researchers and the general public. We will need your help.

When we started archiving television in 2000, people shrugged and asked, “Why? Isn’t it all junk anyway?” As the saying goes, one person’s junk is another person’s gold. From 2010-18, scholars, pundits and above all, reporters, have spun journalistic gold from the data captured in our 1.5 million hours of television news recordings. Our work has been fueled by visionary funders(1) who saw the potential impact of turning television – from news reports to political ads – into data that can be analyzed at scale. Now the Internet Archive is taking its Television Archive in new directions. In 2018 our goals for television will be: better curation in what we collect; broader collection across the globe; and working with computer scientists interested in exploring our huge data sets. Simply put, our mission is to build and preserve comprehensive collections of the world’s most important television programming and make them as accessible as possible to researchers and the general public. We will need your help.

“Preserving TV news is critical, and at the Internet Archive we’ve decided to rededicate ourselves to growing our collection,” explained Roger MacDonald, Director of Television at the Internet Archive. “We plan to go wide, expanding our archives of global TV news from every continent. We also plan to go deep, gathering content from local markets around the country. And we plan to do so in a sustainable way that ensures that this TV will be available to generations to come.”

Libraries, museums and memory institutions have long played a critical role in preserving the cultural output of our creators. Television falls within that mandate. Indeed some of the most comprehensive US television collections are held by the Library of Congress, Vanderbilt University and UCLA. Now we’d like to engage with a broad range of libraries and memory institutions in the television collecting and curation process. If your organization has a mandate to collect television or researcher demand for this media, we would like to understand your needs and interests. The Internet Archive will undertake collection trials with interested institutions, with the eventual goal of making this work self-sustaining.

Simultaneously, we are looking to engage researchers interested in the non-consumptive analysis of television at scale, in ways that continue to respect the interests of right holders. The tools we’ve created may be useful. For instance, we hope the tools the Internet Archive used to detect TV campaign ads can be applied by researchers in new and different ways. If your organization has interest in computing with television as data at large, we are interested in working with you.

This groundbreaking interface for searching television news, based on the closed captions associated with US broadcasts, was developed between 2009-2012.

A brief history of the Internet Archive’s Television collection:

2000 Working with pioneering engineer, Rod Hewitt, IA begins archiving 20 channels originating from many nations.

Oct. 2001 September 11, 2001 Collection established, and enhanced in 2011.

2009-2012 With funding from the Knight Foundation and many others, we built a service to allow public searching, citation and borrowing of US television news programs on DVD.

2012-2014 Public TV news library launched with tools to search, quote and share streamed snippets from television news.

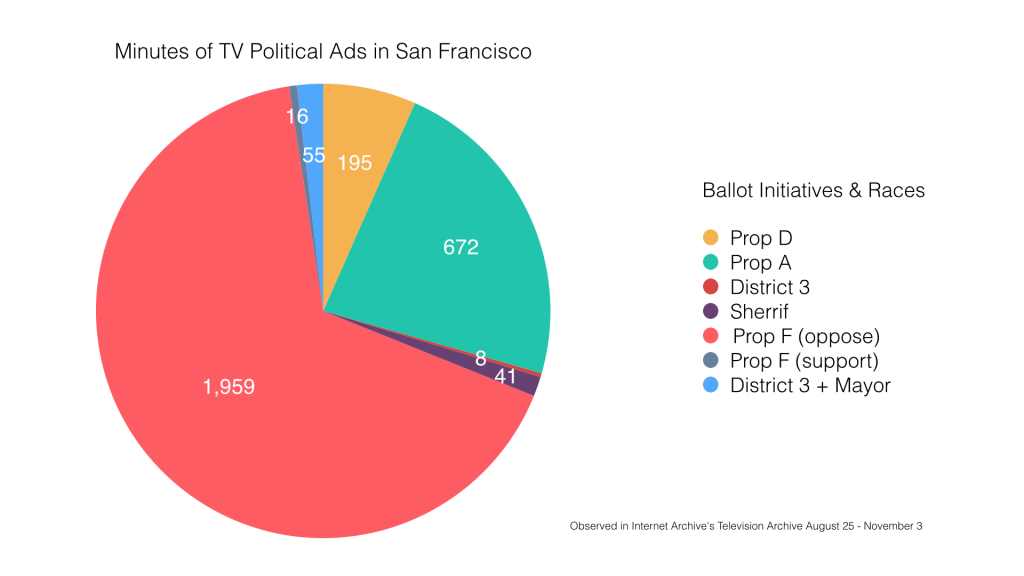

2014 Pilot launched to detect political advertisements broadcast in the Philadelphia region, led to developing open sourced audio fingerprinting techniques.

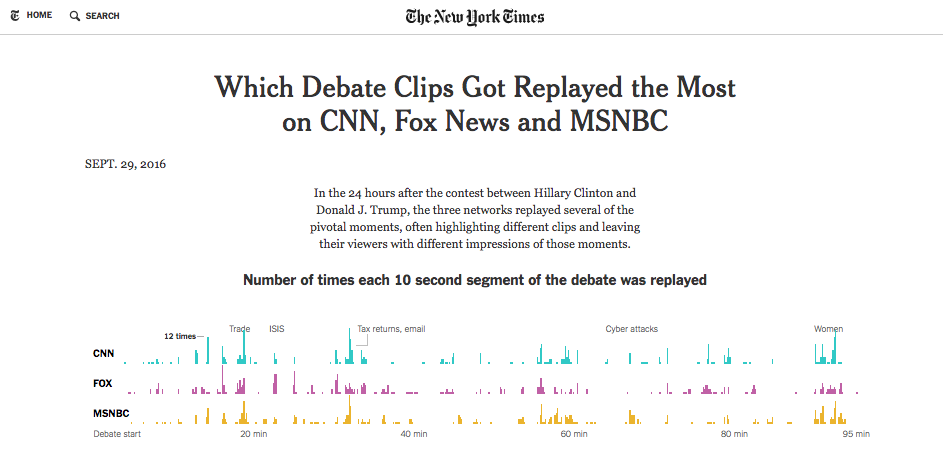

2016 Political ad detection, curation, and access expanded to 28 battleground regions for 2016 elections, enabling journalists to fact check the ads and analyze the data at scale. The same tools helped reporters analyze presidential debates. This resulted in front-page data visualizations in The New York Times, as well as 150+ analyses by news outlets from Fox News to The Economist to FiveThirtyEight.

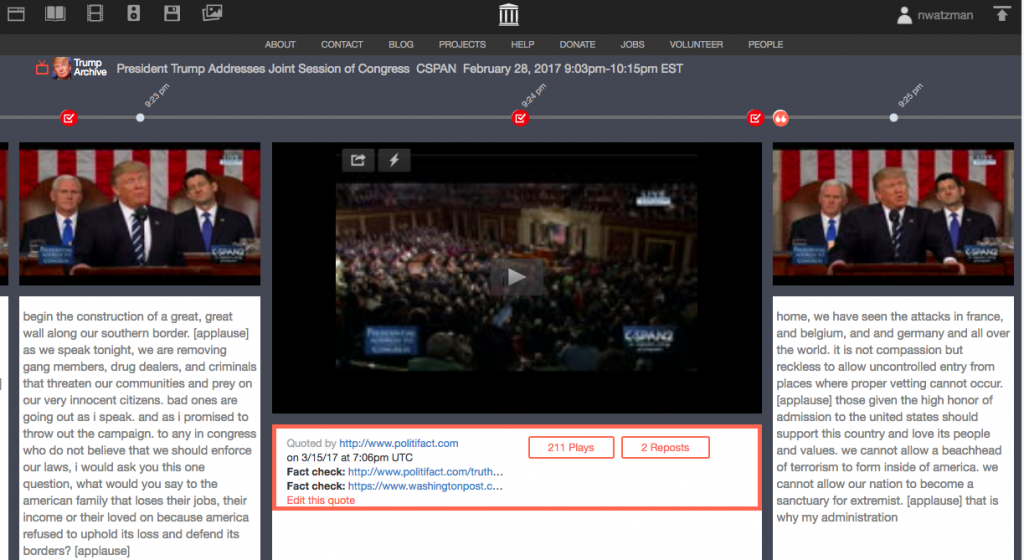

2017-date Experiments with artificial intelligence techniques to employ facial identification, and on-screen optical character recognition to aid searching and data mining of television. Special curated collections of top political leaders and fact-check integrations.

In the run-up to the 2016 presidential elections, journalists at the NYT and elsewhere began analyzing television as data, in this case looking at the different sound bites each network chose to replay.

Embarking on a new direction also means shifting away from some of our current services. Our dedicated television team has been focusing on metadata enhancement and assisting journalists and scholars to use our data. We will be wrapping up some of these free services in the next three to four months. We hope others will take up where we left off and build the tools that will make our collection even more valuable to the public.

Now more than ever in this era of disinformation, our world needs an open, reliable, canonical reference source of television news. This cannot exist without the diligent efforts of technologists, journalists, researchers, and television companies all working together to create a television archive open for all. We hope you will join us!

To learn more about the work of the TV News Archive outreach and metadata innovation team over the last few years, please see our blog posts.

(1) Funding for the Television Archive has come from diverse donors, including the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Democracy Fund, Rita Allen Foundation, craigslist Charitable Fund and The Buck Foundation.